Fish and Wildlife Service employees say they’ve been ordered to fast-track a permit before year’s end, despite the potential risk to polar bears and the tundra.

BY SABRINA SHANKMAN

OCT 29, 2020

The Trump administration aims to have seismic testing permitted in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska by the end of the year. Credit: Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service say they are under pressure from the Trump Administration to deliver a permit that would clear the way for seismic testing in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge by the end of the year.

The permit, called an incidental harassment authorization, allows for a small number of marine mammals—in this case, polar bears—to be disturbed, and is one of at least a dozen permits that must be obtained before seismic testing can begin.

The permitting process normally takes as much as a year to complete.

But a week ago, employees in the Alaska regional office of the wildlife service were told their timeline had been dramatically shortened: They would have four months from start to finish, according to an agency official who requested anonymity because of efforts to crack down on employees who speak out publicly.

Aurelia Skipwith, the director of the Fish and Wildlife Service and a Trump appointee, sent a directive instructing the regional office to get the permit to the agency's headquarters for the next step of the process by Friday, Oct. 30, according to the official, and to finalize it by the end of the year. The deadline left workers scrambling to complete a review based on an application for the seismic testing that isn't yet complete.

"This timing is completely arbitrary," the official said.

At stake is whether the Trump administration will be able to plant a flag along the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge before the end of the president's first term, and before a possible Biden Administration takes office. The seismic testing that is being proposed can cause lasting damage to the tundra in the process of trying to determine how much oil might be underground. It would be a significant first step toward oil development in the region.

"This seems like an effort to try to change the facts on the ground before a potential change in presidential power," said Adam Kolton, executive director of the Alaska Wilderness League. "But none of us can lose sight of the risks here. We're talking about a massive intrusion into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge at the height of polar bear denning season, which could leave scars on the tundra that are permanent."

InsideClimate News emailed detailed questions seeking comment to the Fish and Wildlife Service on Wednesday. By late Friday, no response had been provided. The public affairs office for the agency said that answers to the questions had been submitted to the Interior Department for approval, but that the department was unlikely to take action before Monday. The office offered to provide a response "post-publication." A call directly to Skipwith was referred back to the external affairs office.

Until the passage of the 2017 Tax Act, the 1.6 million acres of coastal plain that the administration has opened to oil exploration were off limits to drilling, much like the rest of the Refuge. The plain is considered the most important onshore denning area for the polar bears that live along the southern Beaufort Sea—a population that scientists have shown has fallen in numbers and suffered health impacts from the climate change-driven retreat of sea ice. The coastal plain is also home to nearly 200 wildlife species, including the Porcupine caribou herd, which holds a sacred place in the culture of the native Gwich'in people.

Since the beginning of the Trump administration, bringing oil development to the Arctic Refuge has been a top priority. The 2017 Tax Act included a provision that required a leasing sale to be held on the coastal plain to raise revenue, and with the Act's passage, decades of protections were removed.

Since then, federal agencies have been racing through the legally-mandated steps to hold a lease sale before the end of 2020. But a tumbling oil market and the coronavirus have made it unclear whether a sale will be held—or, if it is, whether companies will bid. And with the election looming, it seemed as if Trump might be unable to make good on his early promise to develop the Refuge.

That changed on Oct. 23, when the Bureau of Land Management, the Fish and Wildlife Service's parent agency, announced it was considering an application to conduct seismic testing across more than half-a-million acres of the coastal plain, beginning as soon as December.

The truncated timeline has left the Alaska regional office "scrambling to review it on short notice," according to a former member of the Fish and Wildlife Service polar bear program.

And it has alarmed the Gwich'in, who have been fighting to protect the coastal plain. "We felt that they were going to push this through, but this quickly? It's just really insulting to our people," said Bernadette Demientieff, the executive director of the Gwich'in Steering Committee.

To get the review done and still comply with a mandatory 30-day public comment period, the Fish and Wildlife Service employees in the Alaska office have to turn the polar bear permit around at break-neck speed.

A Grid Visible From Outer Space

The plan calls for a crew of 180 people to conduct the seismic survey, which is estimated to take till the end of May, and for the construction of temporary airstrips on the coastal plain. The survey would require 12 "thumper" trucks, which weigh 90,000 pounds each; more than 40 Tucker vehicles; and tractors and 50 camp trailers.

The area selected for the survey is known for a higher density of polar bear dens than other parts of the coastal plain.

"This is the core denning area for the southern Beaufort Sea stock of polar bears," said the Fish and Wildlife Service official.

Derrick Henry, a spokesman for the Bureau of Land Management, said the agency is working on completing an environmental assessment of the survey "to identify impacts and mitigation measures that may be needed to avoid or minimize impacts."

That assessment is based on an application for seismic testing that was filed by Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation (KIC), an Alaska Native corporation, and is not yet ready for review. The public has been given 14 days to comment on the survey, but they must do so based only on the original application from KIC, without input from experts on what the environmental impacts might be. That application is the only publicly available document. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service official, that means the public isn't commenting on the most up-to-date version of the survey plan because, as the agency has worked with the corporation on its application, changes have been made.

Matthew Rexford, president of Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation, said he is confident that through the permitting process they will be able to tailor the plan so it has minimal impacts on the tundra and the species that live there. "The Kaktovikmiut have been using the land known as the 1002 Area or Coastal Plain of ANWR for hundreds of years," Rexford said. "We know the land, the animals, and the environment.

He added, "We believe that through the stringent regulatory environment and the oversight of our Home-Rule borough, the North Slope Borough, all impacts from exploration and development can be mitigated to preserve the area."

The BLM opted to conduct an "environmental assessment," rather than a more rigorous "environmental impact statement" or EIS. That distinction is significant. An environmental assessment is a concise review, rather than the comprehensive dive into environmental impacts that an EIS entails. It also does not require a public comment period.

Ultimately, the public will get two public comment periods on the survey—on the application, and on the polar bear permit. But they will not have a chance to comment on the environmental impacts of the survey.

The administration recently completed an environmental impact statement for its proposed leasing plan in the refuge. That EIS sparked an immediate outcry from conservation groups, who filed a lawsuit claiming the assessment failed to take into account how development in the refuge would affect the environment and the climate.

The EIS for the leasing plan did not take an in-depth look at the impacts of seismic testing. But Henry, the BLM spokesman, said the bureau had received "more than one million comments on the Leasing EIS, some of which were related to seismic exploration." Comments on an earlier application for seismic exploration identified more than 130 issues for the bureau to consider, he added.

As a result, Henry said, "It is not expected that any additional public meetings would provide any new or relevant information to consider" in the development of the environmental assessment of the proposed seismic survey.

That decision does not sit well with environmental groups. "It is unacceptable that BLM is not preparing an environmental impact statement for this massive and damaging proposal," said Bridget Psarianos, a staff attorney with Trustees for Alaska, an environmental law firm. "Seismic exploration and its impacts were not properly considered in the agency's Leasing EIS; BLM kicked the can down the road. Now that we're down the road, the agency must consider the impacts to imperiled polar bears and fragile tundra rather than rush through on a politically motivated timeline."

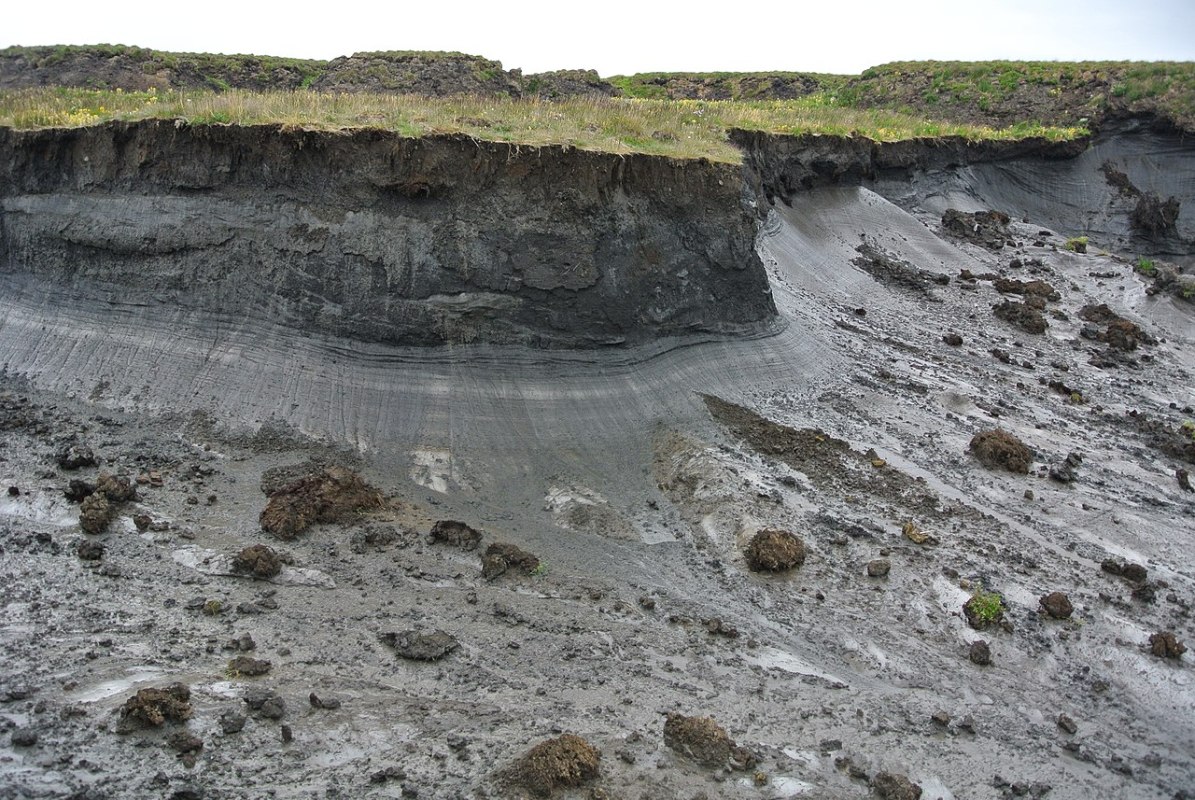

A study published in the journal Ecological Applications earlier this year found that scars from past seismic surveys in the Arctic Refuge remained for decades, and noted that the methods used then were less intrusive than those being proposed now.

Niel Lawrence, the Alaska director of the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that for the government to say that a grid that spans "a third of the sensitive coastal plain—almost a half a million acres—a grid you can see from outer space, that cuts across waterways, that causes the melting of the permafrost" has no significant impact "does not pass the legal laugh test."

Although the application for the seismic survey was filed by the Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation, an Alaska Native corporation, the work would be completed by SAExploration, a contractor that filed an earlier seismic survey application in 2018. That application failed—in part because Fish and Wildlife found it would be devastating to polar bears in the area.

Since then, SAExploration has filed for bankruptcy and now faces accusations of fraud by the Securities and Exchange Commission over charges, filed in early October, that four former executives falsely inflated the company's revenue by roughly $100 million and concealed millions of dollars in theft.

A Different Way to Do It

The 2018 application for a seismic survey was larger in scope than the current application. It called for the survey to be conducted across the entire 1.6 million acres of the coastal plain.

"They were going to carpet bomb the Refuge with seismic lines from early in the year until the snow melted," said a former member of the Fish and Wildlife Service's polar bear program, who also requested anonymity because of not being authorized to discuss the issue. "Basically you'd nail or disturb every den in the Refuge with what they originally proposed."

Though polar bears are the rare bear that does not hibernate, pregnant female bears are in some ways an exception to that rule. In the winter, they enter dens in the snow and they stay there to gestate and birth their cubs. Once the cubs are born, they remain in the den a while longer, until the cubs are strong enough to survive the elements.

It's a crucial time in a polar bear's life, for both the mother and the cubs, and is especially fraught in the Arctic Refuge, according to a study released by the U.S. Geological Survey in October. Fish and Wildlife Service experts have found that because of the declining population rates in the region, the killing of even one polar bear could be detrimental to the species' survival.

A polar bear mother and two yearlings living in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. Credit: Sylvain CORDIER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Moreover, the technology used to locate the dens so that workers can avoid them—called forward-looking infrared systems, or FLIR—is successful less than half the time, according to a study published in 2019.

As the office weighed the 2018 application for the survey, two polar bear scientists—one from Fish and Wildlife and one from the U.S. Geological Survey—created a new model to project how seismic surveys might impact bears.

The model enabled the scientists to quantify how many bears could be affected by a specific project. They found that the plan proposed by SAExploration would be lethal to bears in the region.

"Basically they were inevitably going to run over polar bear dens and either directly kill bears— moms or cubs—or prematurely drive them out of the den, which would result in the cub mortality," said the former member of the agency's polar bear program. "That analysis really started a political firestorm."

The scientists wrote a paper based on their model, laying out a map for how seismic testing could be conducted in a way that would minimize impacts to polar bears, the former member of the Fish and Wildlife polar bear program said. That would require spreading testing out over two years, which could lengthen the time before companies could start drilling. But when the scientists decided to submit the paper to a peer reviewed journal, Interior Department officials denied permission to publish the findings. "Interior tried to squash it," the former agency employee said.

Members of the Alaska regional office pushed back, according to the former employee, and in December 2019, the article was published in the Journal of Wildlife Management.

A few months later, in February 2020, the Interior Department took an unusual step, the Fish and Wildlife official said. It posted the article—which had already been peer-reviewed—in the Federal Register, opening it up to public comment.

Joel Clement, a former Interior Department official who in 2017 blew the whistle on the Trump administration, saying that he was reassigned for speaking about climate change, wrote on a blog published by the Union of Concerned Scientists that the decision to post the article was a blatant violation of scientific integrity. "The only plausible reason for the agency to seek public comment on the study," he wrote, "would be to give agency leadership something to point to, on behalf of fossil fuel interests, if they don't like the scientific results.".

The Fish and Wildlife official who described the pressure on workers to finalize the seismic survey permit said that what happened with the paper was characteristic of how the Interior Department was being run under the Trump administration. "It's complete insanity," said the official, "I've never seen anything like this, and no one I know has seen anything like this at the agency. This administration is treating career employees with a level of contempt and disregard that is deeply disturbing and disappointing."

What's at Stake

The Alaska regional Fish and Wildlife Service office received the current seismic application in August. From the start, they were told to get the polar bear permit completed as soon as possible, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service employee. The employees there told their supervisors the earliest they could get it done was January 21, the day after the winner of the presidential election would be inaugurated.

But then last week, the orders changed, with the new timeline requiring that the permit be finalized by year's end. While the environmental assessment on the seismic program does not have a public comment period, the polar bear permit will have a 30-day comment period. In order to meet Skipwith's end of the year deadline and provide time for the federally-mandated comment period, the analysis is having to be inappropriately cut short, according to the agency.

Demientieff, the Gwich'in steering committee executive director, said that in the rush to plant a flag in the untouched reaches of the Refuge, what stands to be lost is incalculable.

"Protecting this place is very, very deeply important to the Gwich'in and to myself," she said. The coastal plain, which is the calving grounds for the Porcupine Caribou herd, is so sacred, she said, that even during times of food shortages and starvation the Gwich'in will not go there.

"We will never give up or stop protecting this area," she said.