by Frontiers

NOVEMBER 24, 2020

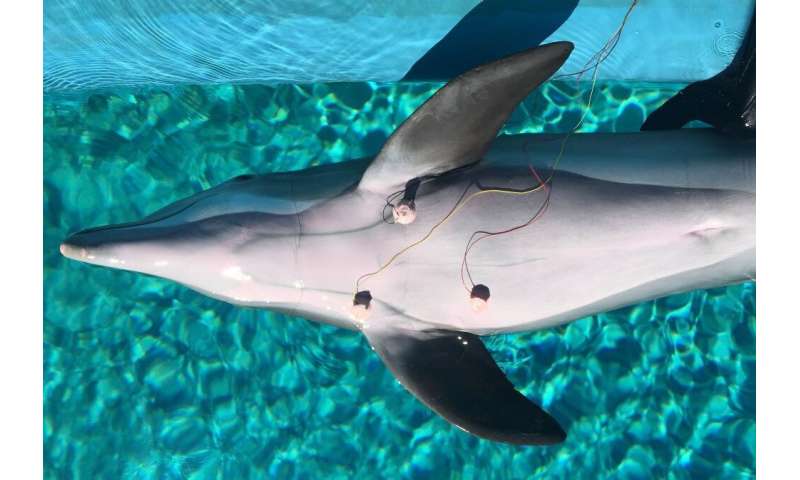

Male bottlenose dolphin with ECG suction cups to monitor heart rate.

Credit: Mirage, Siegfried and Roy's Secret Garden and Dolphin Habitat

Dolphins actively slow down their hearts before diving, and can even adjust their heart rate depending on how long they plan to dive for, a new study suggests. Published in Frontiers in Physiology, the findings provide new insights into how marine mammals conserve oxygen and adjust to pressure while diving.

The authors worked with three male bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), specially trained to hold their breath for different lengths of time upon instruction. "We trained the dolphins for a long breath-hold, a short one, and one where they could do whatever they want", explains Dr. Andreas Fahlman of Fundación Oceanogràfic, Valencia, Spain. "When asked to hold their breath, their heart rates lowered before or immediately as they began the breath-hold. We also observed that the dolphins reduced their heart rates faster and further when preparing for the long breath-hold, compared to the other holds".

The results reveal that dolphins, and possibly other marine mammals, may consciously alter their heart rate to suit the length of their planned dive. "Dolphins have the capacity to vary their reduction in heart rate as much as you and I are able to reduce how fast we breathe", suggests Fahlman. "This allows them to conserve oxygen during their dives, and may also be key to avoiding diving-related problems such as decompression sickness, known as "the bends"".

VIDEO

Dolphins actively slow down their hearts before diving, and can even adjust their heart rate depending on how long they plan to dive for, a new study suggests. Published in Frontiers in Physiology, the findings provide new insights into how marine mammals conserve oxygen and adjust to pressure while diving.

The authors worked with three male bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), specially trained to hold their breath for different lengths of time upon instruction. "We trained the dolphins for a long breath-hold, a short one, and one where they could do whatever they want", explains Dr. Andreas Fahlman of Fundación Oceanogràfic, Valencia, Spain. "When asked to hold their breath, their heart rates lowered before or immediately as they began the breath-hold. We also observed that the dolphins reduced their heart rates faster and further when preparing for the long breath-hold, compared to the other holds".

The results reveal that dolphins, and possibly other marine mammals, may consciously alter their heart rate to suit the length of their planned dive. "Dolphins have the capacity to vary their reduction in heart rate as much as you and I are able to reduce how fast we breathe", suggests Fahlman. "This allows them to conserve oxygen during their dives, and may also be key to avoiding diving-related problems such as decompression sickness, known as "the bends"".

VIDEO

The dolphin has a custom-made spirometry, a device to measure lung function, over the blow hole. The dolphin is then asked to do a breath hold through a hand signal from the trainer and turns around for a brief period to hold its breath underwater. Here, you can see the suction cup ECG electrodes that measure the heart rate. The dolphin then turns again and breathes into the spirometer so the volume of each breath and the oxygen and carbon dioxide of the exhaled air can be measured. Credit: Dolphin Quest - Oahu

Understanding how marine mammals are able to dive safely for long periods of time is crucial to mitigate the health impacts of man-made sound disturbance on marine mammals. "Man-made sounds, such as underwater blasts during oil exploration, are linked to problems such as "the bends" in these animals", continues Fahlman. "If this ability to regulate heart rate is important to avoid decompression sickness, and sudden exposure to an unusual sound causes this mechanism to fail, we should avoid sudden loud disturbances and instead slowly increase the noise level over time to cause minimal stress. In other words, our research may provide very simple mitigation methods to allow humans and animals to safely share the ocean".

The practical challenges of measuring a dolphin's physiological functions, such as heart rate and breathing, have previously prevented scientists from fully understanding changes in their physiology during diving. "We worked with a small sample size of three trained male dolphins housed in professional care", Fahlman explains. "We used custom-made equipment to measure the lung function of the animals, and attached electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors to measure their heart rates".

"The close relationship between the trainers and animals is hugely important when training dolphins to participate in scientific studies", explains Andy Jabas, Dolphin Care Specialist at Siegfried & Roy's Secret Garden and Dolphin Habitat at the Mirage, Las Vegas, United States, home of the dolphins studied here. "This bond of trust enabled us to have a safe environment for the dolphins to become familiar with the specialized equipment and to learn to perform the breath-holds in a fun and stimulating training environment. The dolphins all participated willingly in the study and were able to leave at any time".

Explore furtherThe freediving champions of the dolphin world

Understanding how marine mammals are able to dive safely for long periods of time is crucial to mitigate the health impacts of man-made sound disturbance on marine mammals. "Man-made sounds, such as underwater blasts during oil exploration, are linked to problems such as "the bends" in these animals", continues Fahlman. "If this ability to regulate heart rate is important to avoid decompression sickness, and sudden exposure to an unusual sound causes this mechanism to fail, we should avoid sudden loud disturbances and instead slowly increase the noise level over time to cause minimal stress. In other words, our research may provide very simple mitigation methods to allow humans and animals to safely share the ocean".

The practical challenges of measuring a dolphin's physiological functions, such as heart rate and breathing, have previously prevented scientists from fully understanding changes in their physiology during diving. "We worked with a small sample size of three trained male dolphins housed in professional care", Fahlman explains. "We used custom-made equipment to measure the lung function of the animals, and attached electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors to measure their heart rates".

"The close relationship between the trainers and animals is hugely important when training dolphins to participate in scientific studies", explains Andy Jabas, Dolphin Care Specialist at Siegfried & Roy's Secret Garden and Dolphin Habitat at the Mirage, Las Vegas, United States, home of the dolphins studied here. "This bond of trust enabled us to have a safe environment for the dolphins to become familiar with the specialized equipment and to learn to perform the breath-holds in a fun and stimulating training environment. The dolphins all participated willingly in the study and were able to leave at any time".

Explore furtherThe freediving champions of the dolphin world

More information: Frontiers in Physiology, DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2020.604018 ,