Jon Stinchcomb

Port Clinton News Herald

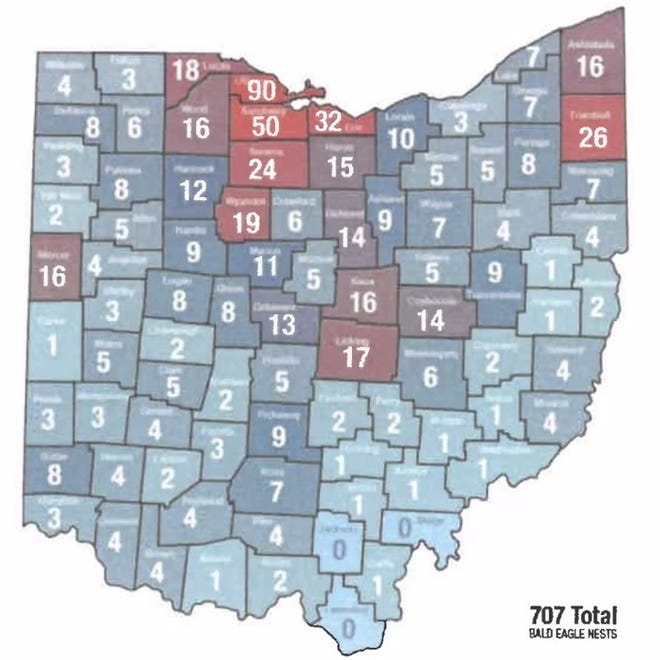

CARROLL TOWNSHIP, Ohio – With the most recent count documenting more than 700 nests across the state, the remarkable recovery of bald eagles in Ohio is reaching new heights.

The recent numbers are a far cry from around 40 years ago, when Ohio was then home to only four breeding pairs of bald eagles.

To Mark Shieldcastle, a wildlife biologist who has been at the forefront of the effort to save Ohio’s bald eagles from that time through today, the current numbers would have been unimaginable.

“Quite honestly, there’s no way I would have ever thought this would have been the number to come out in 2020 — 700 nests, going from 200 a decade ago,” Shieldcastle said. “It really shows what you can do. When humans make their minds up to do something for wildlife, we can do it.”

Shieldcastle worked for over 30 years specializing in avian research at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Wildlife, including spearheading recovery efforts when the United States’ majestic national bird was at its most vulnerable state.

Also a founding member of the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, Shieldcastle eventually retired from his position at the Division of Wildlife in 2012 and now serves as research director for the BSBO.

The number of eagles were dwindling dangerously low around the late 1970s due to several factors, Shieldcastle explained, which were primarily habitat loss, fragmentation and contaminants.

While the pesticide DDT is one of the most widely known contaminants to impact bird populations, which was documented in Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” another significant culprit were PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyl, an industrial pollutant.

From eggs that could not hatch to young birds with terminal deformities, researchers documented a plethora of issues caused by contaminants and other human-related activities.

“There was a lot that we were learning and it was very complex, what was going on,” Shieldcastle said.

But by the early 1980s, efforts to save the bald eagle were underway.

Shieldcastle described Ohio’s bald eagle restoration program as four-pronged, with each of the following components being vital to bringing the bird back to the state: fostering, education, rehabilitation and artificial nest bases.

According to Shieldcastle, Ohio led the country with fostering, where young captive-born eagles were placed in active nests and raised by adults in the wild.

Education was another immensely important component, Shieldcastle said, such as teaching landowners with nests on their property, along with informing politicians, legislators, and the general public.

“We got them to understand the value of wildlife and the importance of this bird,” he said.

Thanks to legislation such as the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, a federal law that Shieldcastle described as the single strongest piece of legislation ever written for wildlife, the bald eagle became “the most protected bird in the world.”

With only four breeding pairs left in Ohio in 1979, it was with just eight birds that the restoration program was built off of, he said. Within a decade, they were seeing some growth in the Lake Erie marshes.

By the turn of the century, “things had really taken off.”

“Ohio felt we could have 12 pairs by 2000. We blew that away in 1992 and it’s continued to grow,” Shieldcastle said.

By 2008, which Shieldcastle said was the last year that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had overseen the organization of the bald eagle monitoring efforts, Ohio had 184 nests.

It was in 2007 that the bald eagle was taken off the endangered species list nationally.

At that point, the number of nests began growing exponentially, which Shieldcastle described as the fruit of the hard work done throughout the 1980s and '90s.

Now, Ohio is quite possibly home to the most eagles it has ever had in its history, he said.

“It’s been an amazing recovery and really it’s because of the productivity, which was coming from the education about being responsible around this bird,” Shieldcastle said.

.

.