Trials will not reveal all the facts on prevention for each new drug – that process could last for years

A volunteer is given the vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca.

Photograph: John Cairns/AP

Robin McKie, Science Editor THE GUARDIAN

Sat 28 Nov 2020

In a few days, researchers plan to solve a medical mystery that threatens to erupt into a major transatlantic battle. Scientists at Oxford University say they intend to publish full, peer-reviewed data, in the journal Lancet, about trials they have completed on their Covid-19 vaccine.

The information, they say, should end mounting controversy about the vaccine’s effectiveness and explain apparent inconsistencies in trial results. Opponents, most of them American, say this is unlikely, and insist new phase 3 trials now need to be restarted from scratch to restore confidence in the vaccine.

An international vaccine battle has begun, one that is likely to be repeated many times over the next year as new, competing vaccines are produced to help rid the world of Covid-19 and doctors attempt to rate their usefulness. How the Oxford vaccine battle proceeds in the next few weeks will have a crucial bearing on the global battle against the pandemic.

“The trouble is that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine received a lot of publicity over the summer and expectations were high,” virologist Professor John Moore, of Weill Cornell Medicine college, New York, told the Observer. “These expectations have not been met and now there is a pushback.”

Robin McKie, Science Editor THE GUARDIAN

Sat 28 Nov 2020

In a few days, researchers plan to solve a medical mystery that threatens to erupt into a major transatlantic battle. Scientists at Oxford University say they intend to publish full, peer-reviewed data, in the journal Lancet, about trials they have completed on their Covid-19 vaccine.

The information, they say, should end mounting controversy about the vaccine’s effectiveness and explain apparent inconsistencies in trial results. Opponents, most of them American, say this is unlikely, and insist new phase 3 trials now need to be restarted from scratch to restore confidence in the vaccine.

An international vaccine battle has begun, one that is likely to be repeated many times over the next year as new, competing vaccines are produced to help rid the world of Covid-19 and doctors attempt to rate their usefulness. How the Oxford vaccine battle proceeds in the next few weeks will have a crucial bearing on the global battle against the pandemic.

“The trouble is that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine received a lot of publicity over the summer and expectations were high,” virologist Professor John Moore, of Weill Cornell Medicine college, New York, told the Observer. “These expectations have not been met and now there is a pushback.”

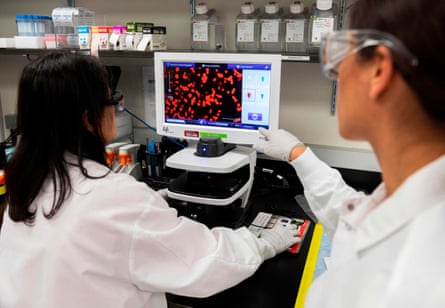

The Novavax vaccine has been developed from moths to manufacture pieces of coronavirus protein that will stimulate anti-Covid responses when injected.

Photograph: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

On Monday, Oxford researchers announced their vaccine had 62% efficacy in most volunteers compared with the recently revealed efficacies of vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, which both topped 90%. But they also revealed that a sub-set of volunteers had been mistakenly given a lower dose of vaccine due to problems manufacturing it. Bizarrely, that lower dosage produced a higher vaccine efficacy: around 90%. The scientists had no explanation for this anomaly.

“The Oxford vaccine was generally not viewed as the best design worldwide, but it was thought it could be adequate for purpose – but now there’s so much uncertainty,” added Moore. “Other vaccines are going to be available in the UK and people are likely to want to use the strongest. That may not be this one.”

Other scientists have defended the Oxford vaccine. Timing was a particular problem, said Joy Leahy, of the Royal Statistical Society. She said: “The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines produced stronger results than expected. If the Oxford-AstraZeneca data had been released first, I believe they would have then met the scientific community’s expectations.”

Professor Helen Fletcher of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said it was remarkable that Oxford and AstraZeneca had gone from square one to creating 100 million doses of a new vaccine in less than a year, adding: “It’s not surprising if some manufacturing issues were still being ironed out when they started clinical trials.”

On Monday, Oxford researchers announced their vaccine had 62% efficacy in most volunteers compared with the recently revealed efficacies of vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, which both topped 90%. But they also revealed that a sub-set of volunteers had been mistakenly given a lower dose of vaccine due to problems manufacturing it. Bizarrely, that lower dosage produced a higher vaccine efficacy: around 90%. The scientists had no explanation for this anomaly.

“The Oxford vaccine was generally not viewed as the best design worldwide, but it was thought it could be adequate for purpose – but now there’s so much uncertainty,” added Moore. “Other vaccines are going to be available in the UK and people are likely to want to use the strongest. That may not be this one.”

Other scientists have defended the Oxford vaccine. Timing was a particular problem, said Joy Leahy, of the Royal Statistical Society. She said: “The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines produced stronger results than expected. If the Oxford-AstraZeneca data had been released first, I believe they would have then met the scientific community’s expectations.”

Professor Helen Fletcher of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said it was remarkable that Oxford and AstraZeneca had gone from square one to creating 100 million doses of a new vaccine in less than a year, adding: “It’s not surprising if some manufacturing issues were still being ironed out when they started clinical trials.”

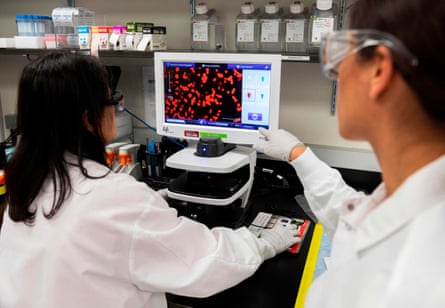

A researcher at the Jenner Institute in Oxford works on the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and Oxford University. Public health officials hope they may soon have access to a vaccine that is cheaper and easier to distribute than some of its rivals. Photograph: John Cairns/AP

The crucial factor is that Covid vaccines work, said Prof Peter Openshaw of Imperial College London. He said: “Each of the trials shows protection, which we did not know would be possible. We have been wanting vaccines for many diseases, such as HIV and malaria, and they haven’t arrived. Results seem to show it can be done for Covid, and that’s very good news.”

This was backed by Kate Bingham, who in May was made chair of the UK vaccine taskforce charged with ensuring Britain was supplied with a Covid vaccine as soon as possible. Bingham told the Observer: “Six months ago, when we started out, we faced the simple fact that no human coronavirus vaccines had ever been developed.

“It was daunting. Our experiences with other coronavirus vaccines, for Sars and for Mers, had been failures and plenty of my peers told me it would take years. Now we have three vaccine candidates from Oxford-AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna, that have been proven to be highly effective against Covid-19 in clinical trials. What scientists have done is completely astonishing.”

Bingham’s taskforce spread its bets by seeking out, and backing, vaccines that were made by the widest variety of techniques, another factor in the current controversy. Pfizer’s vaccine uses virus genes directly to stimulate cells in our bodies to manufacture Covid protein pieces that trigger immune responses. The AstraZeneca vaccine uses another virus to carry those genes into the body.

Others use inactivated Covid viruses to stimulate immune responses, while the US firm Novavax uses a remarkable technique involving the genetic engineering of cells extracted from moths to manufacture pieces of coronavirus protein that will stimulate anti-Covid responses when injected.

Intriguingly, Novavax was facing bleak times at the start of 2020 after the failure of two different vaccine trials using similar technology. Then the pandemic arrived and its moth cell technique was swiftly transferred to Covid-19 vaccine production. Early trials provided strong results and Novavax has since attracted more than $2bn backing from the US government and other agencies.

“This vaccine looks as if it is going to be relatively easy to manufacture,” said virologist Angela Rasmussen, of Columbia University. “Its drawback is that similar protein subunit vaccines – for instance, the hepatitis B vaccine – take multiple shots to build up immunity.”

In Britain, 15,000 volunteers (including Bingham) have been enrolled in phase 3 trials of the Novavax vaccine. The company says it expects to get key data from this group in early 2021 and use that to gain approval for the vaccine. Britain has agreed to buy 60 million doses.

Just how these different vaccines are greeted by scientists remains to be seen. Trial results will be pursued energetically – and the controversy that has surrounded the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine will be repeated. One vaccine may appear to be good at stopping people succumbing to serious illness, but how long might it provide protection? And how good will a vaccine be at preventing virus transmission, and how well will it work in higher-risk groups, such as the elderly? How easy will it be to administer and transport? It will take months if not years to answer all these questions for each vaccine.

The good news for Britain is that it is very well placed to make major contributions to resolving these issues, said Jonathan Pearce, interim director of the Medical Research Council’s Covid-19 response. He added: “The UK has superb medical data resources and an integrated healthcare system which have already allowed us to set up a world-leading study for rating Covid-19 treatments. Our opportunity to contribute to the global good is going to be very high.”

The crucial factor is that Covid vaccines work, said Prof Peter Openshaw of Imperial College London. He said: “Each of the trials shows protection, which we did not know would be possible. We have been wanting vaccines for many diseases, such as HIV and malaria, and they haven’t arrived. Results seem to show it can be done for Covid, and that’s very good news.”

This was backed by Kate Bingham, who in May was made chair of the UK vaccine taskforce charged with ensuring Britain was supplied with a Covid vaccine as soon as possible. Bingham told the Observer: “Six months ago, when we started out, we faced the simple fact that no human coronavirus vaccines had ever been developed.

“It was daunting. Our experiences with other coronavirus vaccines, for Sars and for Mers, had been failures and plenty of my peers told me it would take years. Now we have three vaccine candidates from Oxford-AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna, that have been proven to be highly effective against Covid-19 in clinical trials. What scientists have done is completely astonishing.”

Bingham’s taskforce spread its bets by seeking out, and backing, vaccines that were made by the widest variety of techniques, another factor in the current controversy. Pfizer’s vaccine uses virus genes directly to stimulate cells in our bodies to manufacture Covid protein pieces that trigger immune responses. The AstraZeneca vaccine uses another virus to carry those genes into the body.

Others use inactivated Covid viruses to stimulate immune responses, while the US firm Novavax uses a remarkable technique involving the genetic engineering of cells extracted from moths to manufacture pieces of coronavirus protein that will stimulate anti-Covid responses when injected.

Intriguingly, Novavax was facing bleak times at the start of 2020 after the failure of two different vaccine trials using similar technology. Then the pandemic arrived and its moth cell technique was swiftly transferred to Covid-19 vaccine production. Early trials provided strong results and Novavax has since attracted more than $2bn backing from the US government and other agencies.

“This vaccine looks as if it is going to be relatively easy to manufacture,” said virologist Angela Rasmussen, of Columbia University. “Its drawback is that similar protein subunit vaccines – for instance, the hepatitis B vaccine – take multiple shots to build up immunity.”

In Britain, 15,000 volunteers (including Bingham) have been enrolled in phase 3 trials of the Novavax vaccine. The company says it expects to get key data from this group in early 2021 and use that to gain approval for the vaccine. Britain has agreed to buy 60 million doses.

Just how these different vaccines are greeted by scientists remains to be seen. Trial results will be pursued energetically – and the controversy that has surrounded the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine will be repeated. One vaccine may appear to be good at stopping people succumbing to serious illness, but how long might it provide protection? And how good will a vaccine be at preventing virus transmission, and how well will it work in higher-risk groups, such as the elderly? How easy will it be to administer and transport? It will take months if not years to answer all these questions for each vaccine.

The good news for Britain is that it is very well placed to make major contributions to resolving these issues, said Jonathan Pearce, interim director of the Medical Research Council’s Covid-19 response. He added: “The UK has superb medical data resources and an integrated healthcare system which have already allowed us to set up a world-leading study for rating Covid-19 treatments. Our opportunity to contribute to the global good is going to be very high.”