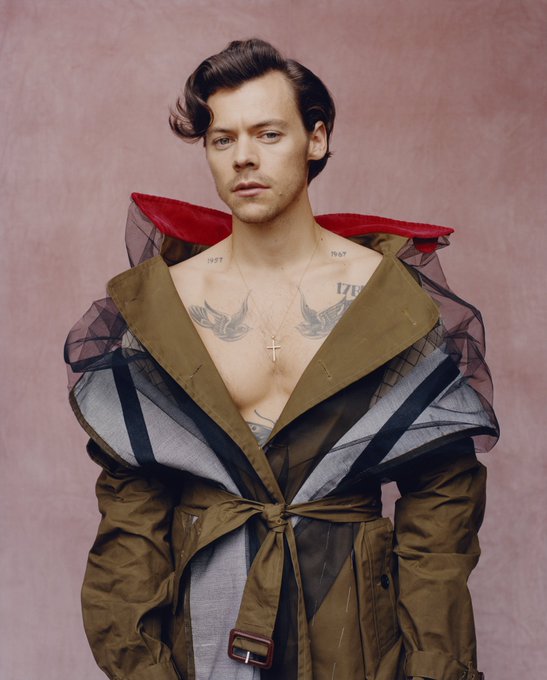

Harry Styles Mocks Candace Owens’ ‘Bring Back Manly Men’ ‘Vogue’ Comments, Talks Challenging Traditional Gender Boundaries Through Fashion

Harry Styles discusses his love of fashion, quarantine, Black Lives Matter, and more in a new interview with Variety

.

© Credit: Parker Woods/Variety

Styles, who is the publication's 2020 Hitmaker of the Year, says of challenging traditional gender boundaries through fashion: “To not wear [something] because it’s females’ clothing, you shut off a whole world of great clothes. And I think what’s exciting about right now is you can wear what you like. It doesn’t have to be X or Y. Those lines are becoming more and more blurred.”

The musician recently hit headlines after right-wing commentator Candace Owens slammed him for wearing a dress and feminine garments for his Vogue cover shoot.

Styles appeared to mock Owens' "bring back manly men" remarks as he shared a snap from the Variety shoot of himself eating a banana alongside that same caption.

Styles, who is the publication's 2020 Hitmaker of the Year, says of challenging traditional gender boundaries through fashion: “To not wear [something] because it’s females’ clothing, you shut off a whole world of great clothes. And I think what’s exciting about right now is you can wear what you like. It doesn’t have to be X or Y. Those lines are becoming more and more blurred.”

The musician recently hit headlines after right-wing commentator Candace Owens slammed him for wearing a dress and feminine garments for his Vogue cover shoot.

Styles appeared to mock Owens' "bring back manly men" remarks as he shared a snap from the Variety shoot of himself eating a banana alongside that same caption.

There is no society that can survive without strong men. The East knows this. In the west, the steady feminization of our men at the same time that Marxism is being taught to our children is not a coincidence.

It is an outright attack.

Bring back manly men.

RELATED: Harry Styles Talks Black Lives Matter And Removing Barriers & Labels In ‘Vogue’ Interview

Styles talks about his self-reflection during COVID quarantine, telling the mag: “It’s been a pause that I don’t know if I would have otherwise taken. I think it’s been pretty good for me to have a kind of stop, to look and think about what it actually means to be an artist, what it means to do what we do and why we do it. I lean into moments like this — moments of uncertainty.”

He then discusses his decision to speak out publicly following the killing of George Floyd: “Talking about race can be really uncomfortable for everyone. I had a realization that my own comfort in the conversation has nothing to do with the problem — like, that’s not enough of a reason to not have a conversation.

"Looking back, I don’t think I’ve been outspoken enough in the past. Using that feeling has pushed me forward to being open and ready to learn. How can I ensure from my side that in 20 years, the right things are still being done and the right people are getting the right opportunities? That it’s not a passing thing?”

Styles recently nabbed a string of 2021 Grammy nominations for his 2019 album Fine Line, telling Variety: “It’s always nice to know that people like what you’re doing, but ultimately — and especially working in a subjective field — I don’t put too much weight on that stuff. I think it’s important when making any kind of art to remove the ego from it.”

Citing the painter Matisse, he adds: “It’s about the work that you do when you’re not expecting any applause.”

"Looking back, I don’t think I’ve been outspoken enough in the past. Using that feeling has pushed me forward to being open and ready to learn. How can I ensure from my side that in 20 years, the right things are still being done and the right people are getting the right opportunities? That it’s not a passing thing?”

Styles recently nabbed a string of 2021 Grammy nominations for his 2019 album Fine Line, telling Variety: “It’s always nice to know that people like what you’re doing, but ultimately — and especially working in a subjective field — I don’t put too much weight on that stuff. I think it’s important when making any kind of art to remove the ego from it.”

Citing the painter Matisse, he adds: “It’s about the work that you do when you’re not expecting any applause.”