The Long Shadow of Racial Fascism

Recent debates have centered on whether it’s appropriate to compare Trump to European fascists. But radical Black thinkers have long argued that racial slavery created its own unique form of American fascism.

ALBERTO TOSCANO

In the wake of the 2016 election, public intellectuals latched onto the new administration’s organic and ideological links with the alt- and far right. But a mass civic insurgency against racial terror—and the federal government’s authoritarian response—has pushed hitherto cloistered academic debates about fascism into the mainstream, with Peter E. Gordon, Samuel Moyn, and Sarah Churchwell taking to the pages of the New York Review of Books to hash out whether it is historically apt or politically useful to call Trump a fascist. The F-word has also been making unusual forays into CNN, the New York Times, and mainstream discourse. The increasing prospect that any transfer of power will be fraught—Trump has hinted he will not accept the results if he loses—has further intensified the stakes, with even the dependable neoliberal cheerleader Thomas Friedman conjuring up specters of civil war.

Is it historically apt or politically useful to call Trump a fascist? The long history of Black radical thinking about fascism and anti-fascist resistance provides direction in this debate.

Notwithstanding the changing terrain, talk of fascism has generally stuck to the same groove, namely asking whether present phenomena are analogous to those familiar from interwar European dictatorships. Sceptics of comparison underscore the way in which the analogy of fascism can either treat the present moment as exceptional, papering over the history of distinctly American forms of authoritarianism, or, alternatively, be so broad as to fail to define what is unique about our current predicament. Analogy’s advocates point to the need to detect family resemblances with past despotisms before it’s too late, often making their case by advancing some ideal-typical checklist, whether in terms of the elements of or the steps toward fascism. But what if our talk of fascism were not dominated by the question of analogy?

Attending to the long history of Black radical thinking about fascism and anti-fascist resistance—to what Cedric Robinson called a “Black construction of fascism” alternative to the “historical manufacture of fascism as a negation of Western Geist”—could serve to dislodge the debate about fascism from the deadlock of analogy, providing the resources to confront our volatile interregnum.

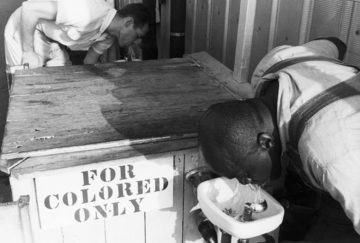

Long before Nazi violence came to be conceived of as beyond analogy, Black radical thinkers sought to expand the historical and political imagination of an anti-fascist left. They detailed how what could seem, from a European or white vantage point, to be a radically new form of ideology and violence was, in fact, continuous with the history of colonial dispossession and racial slavery.

Black radical thinkers have long sought to expand the historical and political imagination of an anti-fascist left, revealing fascism as a continuation of colonial dispossession and racial slavery.

Pan-Africanist George Padmore, breaking with the Communist International over its failure to see the likenesses between “democratic” imperialism and fascism, would write in How Britain Rules Africa (1936) of settler-colonial racism as “the breeding-ground for the type of fascist mentality which is being let loose in Europe today.” He would go on to see in South Africa “the world’s classic Fascist state,” grounded on the “unity of race as against class.” Padmore’s “Colonial Fascism” thus anticipated Aimé Césaire’s memorable description of fascism as the boomerang effect of European imperialist violence.

African American anti-fascists shared the anti-colonial analysis that the Atlantic world’s history of racial violence belied the novelty of intra-European fascism. Speaking in Paris at the Second International Writers Congress in 1937, Langston Hughes declared: “We Negroes in America do not have to be told what fascism is in action. We know. Its theories of Nordic supremacy and economic suppression have long been realities to us.” It was an insight that certainly would not have surprised any reader of W. E. B. Du Bois’s monumental reckoning with the history of U.S. racial capitalism, Black Reconstruction in America (1935). As Amiri Baraka would suggest much later, building on Du Bois’s passing mentions of fascism, the overthrow of Reconstruction enacted a “racial fascism” that long predated Hitlerism in its use of racial terror, conscription of poor whites, and manipulation of (to quote the famous definition of fascism by Georgi Dimitrov) “the most reactionary, most chauvinistic, and most imperialist sector of finance capital.”

In this view, a U.S. racial fascism could go unremarked because it operated on the other side of the color line, just as colonial fascism took place far from the imperial metropole. As Bill V. Mullen and Christopher Vials have suggested in their vital The US Antifascism Reader (2020):

For people of color at various historical moments, the experience of racialization within a liberal democracy could have the valence of fascism. That is to say, while a fascist state and a white supremacist democracy have very different mechanisms of power, the experience of racialized rightlessness within a liberal democracy can make the distinction between it and fascism murky at the level of lived experience. For those racially cast aside outside of liberal democracy’s system of rights, the word ‘fascism’ does not always conjure up a distant and alien social order.

Or, as French writer Jean Genet observed on May 1, 1970, at a rally in New Haven for the liberation of Black Panther Party chairman Bobby Seale: “Another thing worries me: fascism. We often hear the Black Panther Party speak of fascism, and whites have difficulty accepting the word. That’s because whites have to make a great effort of imagination to understand that blacks live under an oppressive fascist regime.”

It was largely thanks to the Panthers that the term “fascism” returned to the forefront of radical discourse and activism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The United Front Against Fascism conference held in Oakland in 1969 brought together a wide swathe of the Old and New Lefts, as well as Asian American, Chicano, Puerto Rican (Young Lords), and white Appalachian (Young Patriots Organization) activists who had developed their own perspectives on U.S. fascism—for instance, by foregrounding the experience of Japanese internment during World War II. In a striking indication of the peculiarities and continuities of U.S. anti-fascist traditions, among the chief planks of the conference was the notionally reformist demand for community or decentralized policing—to remove racist white officers from Black neighborhoods and exert local checks on law enforcement.

Political prisoners close to the Panthers theorized specifically about what we could call “late fascism” (by analogy with “late capitalism”) in the United States. At the same time that debates about “new fascisms” were polarizing radical debate across Europe, the writing and correspondence of Angela Y. Davis and George Jackson generated a theory of fascism from the lived experience of the violent nexus between the carceral state and racial capitalism. Davis, the Black Marxist and feminist scholar, needs little introduction, her 1970 imprisonment on trumped-up conspiracy charges having rocketed her to the status of household name in the United States and an icon of solidarity worldwide. Fewer remember that the conspiracy charge against Davis arose from an armed courtroom attack by her seventeen-year-old bodyguard, Jonathan Jackson, with the goal of forcing the release of the Soledad Brothers, three African American prisoners facing the death penalty for the killing of a white prison guard. Among them was Jonathan’s older brother, the incarcerated Black revolutionary George Jackson, with whom Davis corresponded extensively. Jackson was killed by a prison sniper during an escape attempt on August, 21, 1971, a few days before the Soledad Brothers were to be tried.

In one of his prison letters on fascism, posthumously collected in Blood in My Eye (1972), Jackson offered the following reflection:

When I am being interviewed by a member of the old guard and point to the concrete and steel, the tiny electronic listening device concealed in the vent, the phalanx of goons peeping in at us, his barely functional plastic tape-recorder that cost him a week’s labor, and point out that these are all manifestations of fascism, he will invariably attempt to refute me by defining fascism simply as an economic geo-political affair where only one party is allowed to exist aboveground and no opposition political activity is allowed.

Jackson encourages us to consider what happens to our conceptions of fascism if we take our bearings not from analogies with the European interwar scene, but instead from the materiality of the prison-industrial complex, from the “concrete and steel,” from the devices and personnel of surveillance and repression.

In their writing and correspondence, marked by interpretive differences alongside profound comradeship, Davis and Jackson identify the U.S. state as the site for a recombinant or even consummate form of fascism. Much of their writing is threaded through Marxist debates on the nature of monopoly capitalism, imperialism and capitalist crises, as well as, in Jackson’s case, an effort to revisit the classical historiography on fascism. On these grounds, Jackson and Davis stress the disanalogies between present forms of domination and European exemplars, but both assert the privileged vantage point provided by the view from within a prison-judicial system that could accurately be described as a racial state of terror.

Angela Y. Davis and George Jackson saw the U.S. state—the carceral state and racial capitalism—as the site of fascism. This fascism originated from liberal democracy itself.

This both echoes and departs from the Black radical theories of fascism, such as Padmore’s or Césaire’s, which emerged from the experience of the colonized. The new, U.S. fascism that Jackson and Davis strive to delineate is not an unwanted return from the “other scene” of colonial violence, but originates from liberal democracy itself. Indeed, it was a sense of the disavowed bonds between liberal and fascist forms of the state which, for Davis, was one of the great lessons passed on by Herbert Marcuse, whose grasp of this nexus in 1930s Germany allowed him to discern the fascist tendencies in the United States of his exile.

Both Davis and Jackson also stress the necessity to grasp fascism not as a static form but as a process, inflected by its political and economic contexts and conjunctures. Checklists, analogies, or ideal-types cannot do justice to the concrete history of fascism. Jackson writes of “the defects of trying to analyze a movement outside of its process and its sequential relationships. You gain only a discolored glimpse of a dead past.” He remarks that fascism “developed from nation to nation out of differing levels of traditionalist capitalism’s dilapidation.”

Where Jackson and Davis echo their European counterparts is in the idea that “new” fascisms cannot be understood without seeing them as responses to the insurgencies of the 1960s and early 1970s. For Jackson, fascism is fundamentally a counterrevolutionary form, as evidenced by the violence with which it represses any consequential threat to the state. But fascism does not react immediately against an ascendant revolutionary force; it is a kind of delayed counterrevolution, parasitic on the weakness or defeat of the anti-capitalist left, “the result of a revolutionary thrust that was weak and miscarried—a consciousness that was compromised.” Jackson argues that U.S.-style fascism is a kind of perfected form—all the more insidiously hegemonic because of the marriage of monopoly capital with the (racialized) trappings of liberal democracy. As he declared:

Fascism has established itself in a most disguised and efficient manner in this country. It feels so secure that the leaders allow us the luxury of a faint protest. Take protest too far, however, and they will show their other face. Doors will be kicked down in the night and machine-gun fire and buckshot will become the medium of exchange.

In Davis’s concurrent theorizing, the carceral, liberationist perspective on fascism has a different inflection. For Davis, fascism in the United States takes a preventive and incipient form. The terminology is adapted from Marcuse, who remarked, in an interview from 1970, “In the last ten to twenty years we’ve experienced a preventative counterrevolution to defend us against a feared revolution, which, however, has not taken place and doesn’t stand on the agenda at the moment.” Some of the elements of Marcuse’s analysis still resonate (particularly poignant, in the wake of Breonna Taylor’s murder by police, is his mention of no-knock warrants):

The question is whether fascism is taking over in the United States. If by that we understand the gradual or rapid abolition of the remnants of the constitutional state, the organization of paramilitary troops such as the Minutemen, and granting the police extraordinary legal powers such as the notorious no-knock law which does away with the inviolability of the home; if one looks at the court decisions of recent years; if one knows that special troops—so-called counterinsurgency corps—are being trained in the United States for possible civil war; if one looks at the almost direct censorship of the press, television and radio: then, as far as I’m concerned, one can speak with complete justification of an incipient fascism. . . . American fascism will probably be the first which comes to power by democratic means and with democratic support.

Davis was drawn to Marcuse’s contention that “fascism is the preventive counter-revolution to the socialist transformation of society” because of how it resonated with racialized communities and activists. In the experience of many Black radicals, the aspect of their revolutionary politics that most threatened the state was not the endorsement of armed struggle, but rather the “survival programs,” those enclaves of autonomous social reproduction facilitated by the Panthers and more broadly practiced by Black movements. While nominally mobilized against the threat of armed insurrection, the ultimate target of counterinsurgency were these experiments with social life outside and against the racial state—especially when they edged toward what Huey P. Newton named “revolutionary intercommunalism.”

Race, gender, and class determine how fascist the country might seem to any given individual.

What can be gleaned from Davis’s account is the way that fascism and democracy can be experienced very differently by different segments of the population. In this regard, Davis is attuned to the ways in which race and gender, alongside class, can determine how fascist the country seems to any given individual. As Davis puts it, fascism is “primarily restricted to the use of the law-enforcement-judicial-penal apparatus to arrest the overt and latent revolutionary trends among nationally oppressed people, tomorrow it may attack the working class en masse and eventually even moderate democrats.” But the latter are unlikely to fully perceive this phenomenon because of the manufactured invisibility of the site of the state’s maximally fascist presentation, namely, prisons with their “totalitarian aspirations.”

The kind of fascism diagnosed by Davis is a “protracted social process,” whose “growth and development are cancerous in nature.” We thus have the correlation in Davis’s analysis between, on the one hand, the prison as a racialized enclave or laboratory and, on the other, the fascist strategy of counterrevolution, which flow through society at large but are not experienced equally by everyone everywhere. As Davis has written more recently:

The dangerous and indeed fascistic trend toward progressively greater numbers of hidden, incarcerated human populations is itself rendered invisible. All that matters is the elimination of crime—and you get rid of crime by getting rid of people who, according to the prevailing racial common sense, are the most likely people to whom criminal acts will be attributed.

CONTINUE READING HERE

Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review:

Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review: