In his first few days in office, President Joe Biden moved swiftly to deliver on promises to Hispanic voters, signing a directive to protect "Dreamers" from deportation and unveiling an outline for sweeping changes to immigration laws.

Tuesday afternoon, the president announced a task force to reunite families separated at the border and an executive order that reviews a Trump administration policy requiring migrants seeking asylum to wait in Mexico while they plead their case.

But executive actions are not permanent, and the White House already has begun tamping down hopes for passage of an omnibus reform measure.

That leaves some Latino advocacy groups looking at an untested fallback plan: a mass presidential pardon for at least some of the estimated 11 million people in the country illegally.

“We believe this is a viable option if the Senate fails to act on comprehensive immigration reform,” said Domingo Garcia, president of the League of United Latin American Citizens.

Reversing Trump: Biden to create task force to reunite families separated at border, sign order to review asylum program

Reuniting families: 628 parents remain separated from their kids after Trump's zero-tolerance border policy. Biden wants to find them.

Hector Sánchez Barba, executive director at Mi Familia Vota,said congressional action is the top priority, and Biden has put forth “the most progressive plan I’ve seen, probably in our history.”

But if Congress fails to reform immigration laws, he said, “I am in an action mode. … We will advocate for anything that reverses the extremism and damage” of the Trump administration.

It is unclear how Biden would respond if pressed to pursue a mass pardon. Moreover, not all immigrant-rights advocates want to pursue that controversial path while there is a chance Congress could act.

Jorge Loweree, policy director with the American Immigration Council, said a presidential pardon for immigration violators falls short because “it wouldn’t put people on a path to citizenship; it would just cure one of the barriers to getting there.”

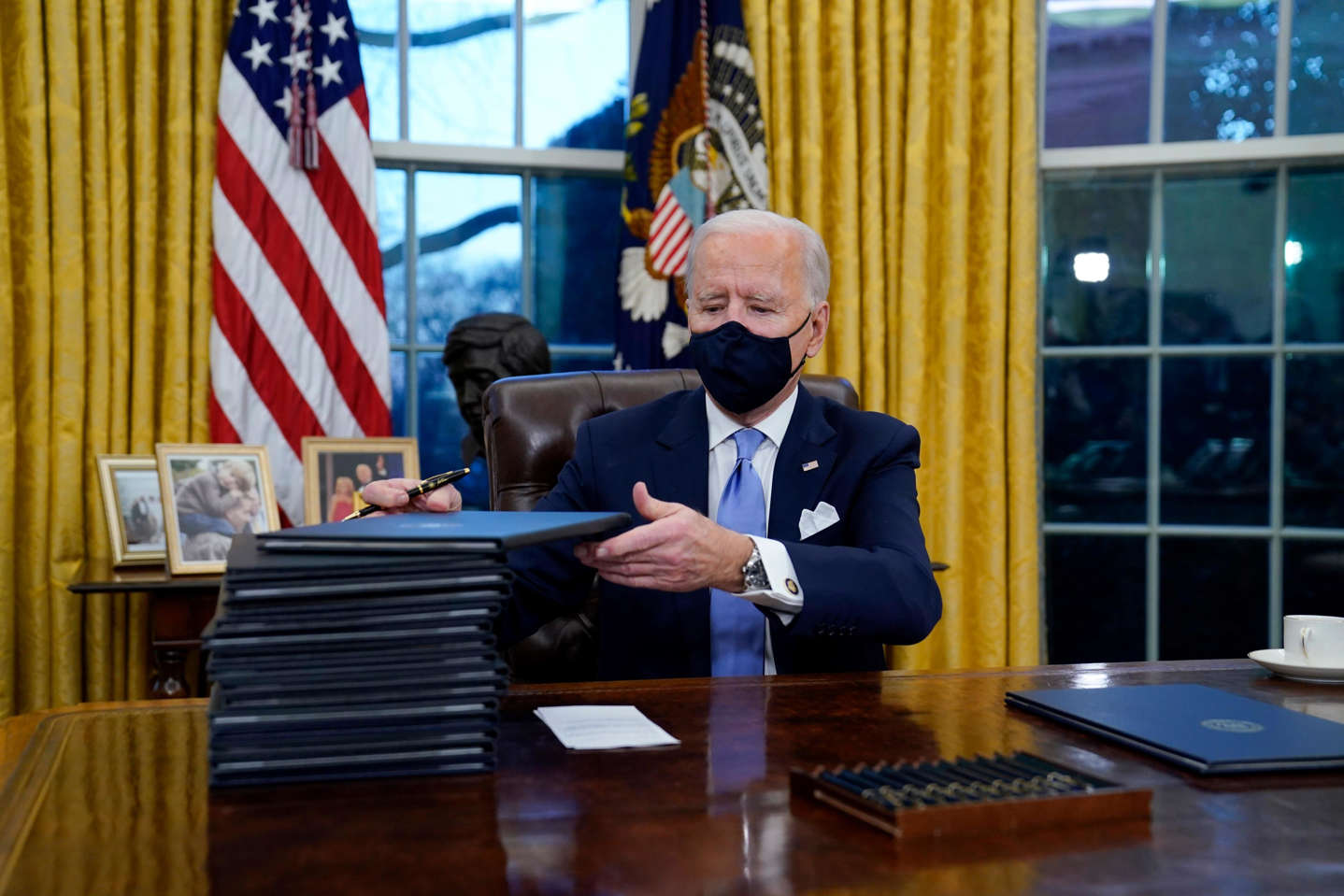

© Evan Vucci, AP President Joe Biden signs his first executive orders in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington. Six of Biden's 17 first-day executive orders dealt with immigration, such as halting work on a border wall in Mexico and lifting a travel ban on people from several predominantly Muslim countries.

The clemency proposition is not new. In late 2016, before Trump was inaugurated, Garcia and others feared the new president would launch draconian deportations of undocumented immigrants – especially those brought to the United States as children, called "Dreamers" based on never-passed proposals in Congress called the DREAM Act.

Dozens of advocacy groups and at least three Democrats in Congress implored then-President Barack Obama to issue last-minute amnesty. In a letter to the president, Rep. Zoe Lofgren of California and her colleagues described the proposed pardon as “a matter of life and death” for many of the nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants.

Obama denied the request. And Trump carried out his promised crackdown.

The clemency proposition is not new. In late 2016, before Trump was inaugurated, Garcia and others feared the new president would launch draconian deportations of undocumented immigrants – especially those brought to the United States as children, called "Dreamers" based on never-passed proposals in Congress called the DREAM Act.

Dozens of advocacy groups and at least three Democrats in Congress implored then-President Barack Obama to issue last-minute amnesty. In a letter to the president, Rep. Zoe Lofgren of California and her colleagues described the proposed pardon as “a matter of life and death” for many of the nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants.

Obama denied the request. And Trump carried out his promised crackdown.

© Richard Vogel, AP Protesters gather at the federal courthouse in Los Angeles in June 2018 to object to the Trump administration's separation of migrant children from their parents at the U.S. border with Mexico.

Biden acts to undo Trump's immigration policies

Trump’s promise of a border wall was the hallmark of his first presidential campaign. In office, he tried to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which allows people brought to the U.S. as children to remain in the country, but he was largely blocked by court rulings. As part of a "zero tolerance" policy for illegal entry, children were separated from parents at the southern border. The administration tried to prevent most migrants from claiming political asylum and required those seeking asylum to wait in Mexico.

Cut to 2020 and Biden’s platform was the polar opposite: He vowed to stop construction of Trump's southern border wall, protect "Dreamers" and overhaul U.S. immigration laws that have not changed significantly in three decades.

On his first day in office, Biden signed an executive memorandum reinstating DACA and unveiled a sweeping immigration reform package.

Under that proposal, agricultural workers, people who arrived illegally as children and immigrants with what is known as temporary protected status would immediately qualify for green cards – giving them legal status and a right to work. Other undocumented immigrants in the United States as of Jan. 1 would receive temporary legal status for five years, with a path to citizenship if they passed background checks and paid taxes

.

© Mario Tama, Getty Images Mexican immigrant Vicky Uriostegui, who has lived in the U.S. for 27 years, hauls out water hoses at dawn on a farm in fields near Turlock, California. Agriculture is the main economic driver in the region, and most field work is done by immigrants.

Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, a Republican who had supported a bipartisan immigration reform plan, ripped Biden’s legislative plan as “mass amnesty” – the exact words used by Trump loyalist Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo.

Meanwhile, congressional Democrats who once pushed Obama to pardon "Dreamers" went silent.

Lofgren, a former immigration attorney and the most recent chair of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship, declined to comment on whether she may ask Biden to use his pardon power.

In a written statement, she said she’s focused on working with the president “to advance our shared bold vision to reform our country’s immigration system.”

Other members of the House and Senate did not respond to emails and calls. Neither did a White House spokesman.

A constitutional ‘gray area’

On Jan. 21, 1977, more than 570,000 American offenders were given pardons.

It was the first full day in office for President Jimmy Carter, and he used it to grant amnesty to Vietnam-era draft dodgers. Nearly 210,000 had been charged with violating the Selective Service Act. Another 360,000 dodged but were not prosecuted.

Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, a Republican who had supported a bipartisan immigration reform plan, ripped Biden’s legislative plan as “mass amnesty” – the exact words used by Trump loyalist Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo.

Meanwhile, congressional Democrats who once pushed Obama to pardon "Dreamers" went silent.

Lofgren, a former immigration attorney and the most recent chair of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship, declined to comment on whether she may ask Biden to use his pardon power.

In a written statement, she said she’s focused on working with the president “to advance our shared bold vision to reform our country’s immigration system.”

Other members of the House and Senate did not respond to emails and calls. Neither did a White House spokesman.

A constitutional ‘gray area’

On Jan. 21, 1977, more than 570,000 American offenders were given pardons.

It was the first full day in office for President Jimmy Carter, and he used it to grant amnesty to Vietnam-era draft dodgers. Nearly 210,000 had been charged with violating the Selective Service Act. Another 360,000 dodged but were not prosecuted.

© AP President Jimmy Carter extended a pardon to over 200,000 Vietnam anti-draft resisters in 1977.

Article II, Clause 1 of the Constitution is terse and clear: “The President … shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

The authority covers all violations of federal law and may be used absolutely or conditionally, according to Cornell University Law School’s Legal Information Institute. It includes a presumed power “to pardon specified classes or communities wholesale, in short, the power to amnesty.”

Draft dodgers were nowhere near the first to benefit from mass clemency. Three years earlier, President Gerald Ford granted a conditional pardon to military deserters who were willing to perform public service.

In fact, presidents throughout history granted amnesty to large groups, beginning with the first pardon issued by George Washington in 1795 to participants in a tax revolt known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

Andrew Johnson gave amnesty to all Confederate soldiers after the Civil War. And, in 1902, Theodore Roosevelt granted amnesty to residents of the Philippines – then a U.S. territory – who took part in an insurrection.

Yet, according to legal experts, no president has ever pardoned someone for illegal immigration during the nation’s 245-year history. Presidential pardons historically have addressed criminal violations; entering or being in the country unlawfully is a civil offense unless it's a repeat violation.

Peter Markowitz, a professor at the Cardozo School of Law, acknowledged it's a legal “gray area.” But he said immigration violations – civil or criminal – clearly constitute offenses, and there is “ample reason to believe it is within a president’s pardon authority.”

In a 2017 law review article co-written with Lindsay Nash, Markowitz advocated just such an action, writing: “The President possesses the constitutional authority to categorically pardon broad classes of immigrants for civil violations of the immigration laws and to thereby provide durable and permanent protections against deportation.”

Other experts say it's not so clear-cut, especially without any Supreme Court precedent on pardons for civil offenses. Some argue that a person in the United States illegally commits an ongoing violation. Pardon power may not be exercised to erase future offenses.

Markowitz conceded that executive clemency is an “imperfect solution” because, while it would protect undocumented immigrants from deportation, it would not grant them legal status or rights.

“Everybody would prefer that this type of durable protection be delivered through legislation,” Markowitz said. But if that proves impossible, clemency at least gives undocumented immigrants peace of mind that they can’t be deported.

'We knew what was coming' with Trump

Despite legal uncertainties and a likely political backlash, Markowitz suggested using pardon power for immigrants would have been worth it four years ago.

In a 2016 opinion piece, Raul A. Reyes, an immigration attorney and member of USA TODAY’s board of contributors, argued that by inviting young "Dreamers" to sign up for DACA, Democrats later exposed them to deportation under the Trump administration.

“It would be a cruel irony if Obama were to turn his back on those here illegally – through no fault of their own – after he helped expose them to risk of deportation,” he concluded.

David Leopold, immigration counsel for America’s Voice, which advocates a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, said it made sense to consider amnesty at the close of Obama’s presidency because Trump had characterized immigrants as criminals.

“We knew the extremism. We knew the xenophobia. We knew what was coming,” said Leopold, who served as a volunteer adviser in the Biden campaign.

But as Biden’s presidency begins, Leopold does not see presidential pardon power as a serious consideration because about 80% of Americans favor changes in law to protect undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children.

“The answer right now is legislative,” Leopold said. “There’s a moment in history right now when we can do it. … Hopefully, Congress will step up to the plate.”

Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, said it would be a legal and political stretch for Biden to simply pardon people who entered the United States unlawfully – a “very out-of-the-blue proposition,” as she put it.

“I’m just having a hard time figuring out how the pardon power … could be justified for that,” said Meissner, now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

Some say it's not the time to talk pardons

Ira Mehlman, media director with the Federation for Immigration Reform, which advocates for strict immigration enforcement and controls, said mass clemency would constitute a “huge overreach” by the president.

In a podcast four years ago, he noted, Cecilia Muñoz, then director of the Obama White House’s Domestic Policy Council, declared that pardons "wouldn’t protect a single soul from deportation.”

Some immigrant rights advocates also resist talk of amnesty, at least for now, for fear it would undermine the push for legislation.

Kristian Ramos of Autonomy Strategies, a communications firm specializing in Latino issues, said Biden’s executive order protecting DACA recipients and immigrants in temporary protected status has, for now, solved the most pressing problem.

“They’re protected,” Ramos said. “He has essentially provided the … reprieve that he could. There’s no real need to pardon them.”

Juliana Macedo do Nascimento, a DACA recipient from Brazil and policy manager with United We Dream, declined to address the amnesty question in a written statement.

Instead, she stressed that Biden and Democrats “have a mandate from the people” to transform America's immigration system. “President Biden must use every tool at his disposal to provide relief for as many people as possible," she said.

“We are tired and not satisfied by executive actions,” said Fernando Garcia, executive director with Border Network for Human Rights. “We need to actually change the law.”

Garcia expressed doubt that Biden would consider amnesty even if legislation fails. “I don’t think it’s realistic that any president is going to say, ‘We’re going to pardon 600,000 Dreamers or 1.2 million Dreamers,’” he said. “And I don’t believe Dreamers are guilty of any offense.”

Loweree, with the American Immigration Council, said America’s support for "Dreamers" is higher than ever, and the president has a “unique opportunity” to fulfill campaign promises beginning with announcements Tuesday.

Loweree said he doesn’t buy into claims that Biden has a debt to Hispanics who helped him get elected. “The issue here isn’t who owes anyone anything,” he said. Rather, it’s about fulfilling a promise made during the Obama administration: "'Dreamers' who came out of the shadows and signed up for DACA were told they’d be protected and allowed to work, not deported."

With that in mind, Loweree suggested talk of presidential amnesty cannot be dismissed entirely: “We expect President Biden will do everything in his power – and consider all options.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: A pardon for 'Dreamers'? Some activists tout amnesty for undocumented immigrants if Congress doesn't act

Article II, Clause 1 of the Constitution is terse and clear: “The President … shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

The authority covers all violations of federal law and may be used absolutely or conditionally, according to Cornell University Law School’s Legal Information Institute. It includes a presumed power “to pardon specified classes or communities wholesale, in short, the power to amnesty.”

Draft dodgers were nowhere near the first to benefit from mass clemency. Three years earlier, President Gerald Ford granted a conditional pardon to military deserters who were willing to perform public service.

In fact, presidents throughout history granted amnesty to large groups, beginning with the first pardon issued by George Washington in 1795 to participants in a tax revolt known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

Andrew Johnson gave amnesty to all Confederate soldiers after the Civil War. And, in 1902, Theodore Roosevelt granted amnesty to residents of the Philippines – then a U.S. territory – who took part in an insurrection.

Yet, according to legal experts, no president has ever pardoned someone for illegal immigration during the nation’s 245-year history. Presidential pardons historically have addressed criminal violations; entering or being in the country unlawfully is a civil offense unless it's a repeat violation.

Peter Markowitz, a professor at the Cardozo School of Law, acknowledged it's a legal “gray area.” But he said immigration violations – civil or criminal – clearly constitute offenses, and there is “ample reason to believe it is within a president’s pardon authority.”

In a 2017 law review article co-written with Lindsay Nash, Markowitz advocated just such an action, writing: “The President possesses the constitutional authority to categorically pardon broad classes of immigrants for civil violations of the immigration laws and to thereby provide durable and permanent protections against deportation.”

Other experts say it's not so clear-cut, especially without any Supreme Court precedent on pardons for civil offenses. Some argue that a person in the United States illegally commits an ongoing violation. Pardon power may not be exercised to erase future offenses.

Markowitz conceded that executive clemency is an “imperfect solution” because, while it would protect undocumented immigrants from deportation, it would not grant them legal status or rights.

“Everybody would prefer that this type of durable protection be delivered through legislation,” Markowitz said. But if that proves impossible, clemency at least gives undocumented immigrants peace of mind that they can’t be deported.

'We knew what was coming' with Trump

Despite legal uncertainties and a likely political backlash, Markowitz suggested using pardon power for immigrants would have been worth it four years ago.

In a 2016 opinion piece, Raul A. Reyes, an immigration attorney and member of USA TODAY’s board of contributors, argued that by inviting young "Dreamers" to sign up for DACA, Democrats later exposed them to deportation under the Trump administration.

“It would be a cruel irony if Obama were to turn his back on those here illegally – through no fault of their own – after he helped expose them to risk of deportation,” he concluded.

David Leopold, immigration counsel for America’s Voice, which advocates a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, said it made sense to consider amnesty at the close of Obama’s presidency because Trump had characterized immigrants as criminals.

“We knew the extremism. We knew the xenophobia. We knew what was coming,” said Leopold, who served as a volunteer adviser in the Biden campaign.

But as Biden’s presidency begins, Leopold does not see presidential pardon power as a serious consideration because about 80% of Americans favor changes in law to protect undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children.

“The answer right now is legislative,” Leopold said. “There’s a moment in history right now when we can do it. … Hopefully, Congress will step up to the plate.”

Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, said it would be a legal and political stretch for Biden to simply pardon people who entered the United States unlawfully – a “very out-of-the-blue proposition,” as she put it.

“I’m just having a hard time figuring out how the pardon power … could be justified for that,” said Meissner, now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

Some say it's not the time to talk pardons

Ira Mehlman, media director with the Federation for Immigration Reform, which advocates for strict immigration enforcement and controls, said mass clemency would constitute a “huge overreach” by the president.

In a podcast four years ago, he noted, Cecilia Muñoz, then director of the Obama White House’s Domestic Policy Council, declared that pardons "wouldn’t protect a single soul from deportation.”

Some immigrant rights advocates also resist talk of amnesty, at least for now, for fear it would undermine the push for legislation.

Kristian Ramos of Autonomy Strategies, a communications firm specializing in Latino issues, said Biden’s executive order protecting DACA recipients and immigrants in temporary protected status has, for now, solved the most pressing problem.

“They’re protected,” Ramos said. “He has essentially provided the … reprieve that he could. There’s no real need to pardon them.”

Juliana Macedo do Nascimento, a DACA recipient from Brazil and policy manager with United We Dream, declined to address the amnesty question in a written statement.

Instead, she stressed that Biden and Democrats “have a mandate from the people” to transform America's immigration system. “President Biden must use every tool at his disposal to provide relief for as many people as possible," she said.

“We are tired and not satisfied by executive actions,” said Fernando Garcia, executive director with Border Network for Human Rights. “We need to actually change the law.”

Garcia expressed doubt that Biden would consider amnesty even if legislation fails. “I don’t think it’s realistic that any president is going to say, ‘We’re going to pardon 600,000 Dreamers or 1.2 million Dreamers,’” he said. “And I don’t believe Dreamers are guilty of any offense.”

Loweree, with the American Immigration Council, said America’s support for "Dreamers" is higher than ever, and the president has a “unique opportunity” to fulfill campaign promises beginning with announcements Tuesday.

Loweree said he doesn’t buy into claims that Biden has a debt to Hispanics who helped him get elected. “The issue here isn’t who owes anyone anything,” he said. Rather, it’s about fulfilling a promise made during the Obama administration: "'Dreamers' who came out of the shadows and signed up for DACA were told they’d be protected and allowed to work, not deported."

With that in mind, Loweree suggested talk of presidential amnesty cannot be dismissed entirely: “We expect President Biden will do everything in his power – and consider all options.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: A pardon for 'Dreamers'? Some activists tout amnesty for undocumented immigrants if Congress doesn't act

© Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) listens as Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill on December 20, 2020 in Washington, DC. A group of 120 Democrats have urged the leadership to repeal a Trump era tax cut that benefits millionaires.

© Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) listens as Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill on December 20, 2020 in Washington, DC. A group of 120 Democrats have urged the leadership to repeal a Trump era tax cut that benefits millionaires.

© Kena Betancur/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images Kena Betancur/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images

© Kena Betancur/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images Kena Betancur/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images