Last week, President Joe Biden reaffirmed his commitment to addressing climate change by creating green energy jobs, building out a "modern and sustainable infrastructure" toward his continued goal of reaching a carbon-free energy sector in the US by 2035.

© Provided by CNN

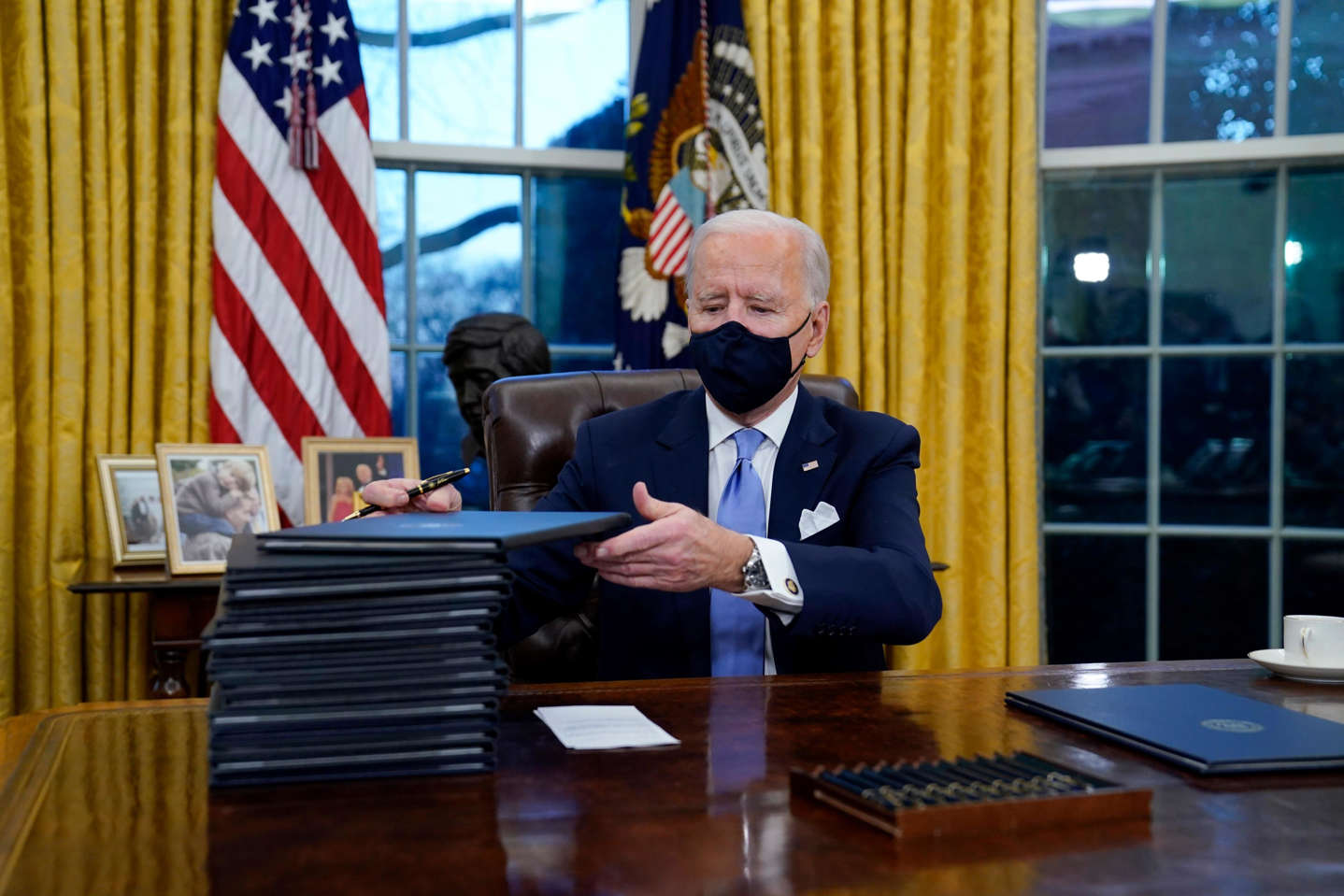

In remarks last week before signing several executive orders focused on his climate agenda, Biden tied his energy policy directly to his plans to rebuild the US economy, citing the need for new, green infrastructure that would generate millions of jobs.

"A key plank of our Build Back Better Recovery Plan is building a modern, resilient climate infrastructure," Biden said, "and clean energy future that will create millions of good-paying union jobs -- not 7, 8, 10, 12 dollars an hour, but prevailing wage and benefits."

During his campaign, Biden's climate agenda included the goal of creating 10 million new jobs related to clean energy on top of the 3 million clean energy jobs the campaign said currently exist. "If executed strategically, our response to climate change can create more than 10 million well-paying jobs in the United States," the plan says, without laying out a timeline for that jobs-creating goal.

It's certainly an ambitious goal. Measuring the feasibility of Biden's plan is quite difficult and depends on several variables, including whether Congress will pass climate legislation. Biden has proposed a $2 trillion climate plan, which includes spending on things such as green energy infrastructure overhaul across the US. Green jobs are also hard to define, with different studies varying widely on what type of jobs they choose to include. For context, it's also worth examining the climate and energy efforts of President Barack Obama, many of which were repealed under President Donald Trump, and the effect they had on green jobs.

Under the eight years of Obama's presidency, the US economy added 11.6 million total new jobs, which only adds to the steepness of Biden's challenge, if as he said during his campaign, he wants to create 10 million new clean energy jobs.

Clean energy job numbers

Measuring the feasibility of Biden's plan first requires establishing what these clean energy-related jobs are and getting good data to establish a baseline and historical trends, which isn't easy.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics studied what it called "green jobs" starting in 2010 before budget cuts stopped the study in 2013. The BLS defined these jobs broadly, in part as those "in which workers' duties involve making their establishment's production processes more environmentally friendly or use fewer natural resources."

This definition was not limited to those who directly contribute to building, installing or maintaining green energy technology but was so broad it included jobs in sewage, publishers of environmental trade publications and environment and science museums, to name a few.

In the survey for 2010, the BLS reported the US had "3.1 million green goods and services (GGS) jobs."

A 2020 report from Environmental Entrepreneurs, a non-partisan group of business leaders focused on environment and the economy, found that "[b]efore the COVID-19 crisis, nearly 3.4 million Americans worked in clean energy—solar, wind, energy efficiency, clean vehicles, and more."

Bob Keefe, executive director of Environmental Entrepreneurs, said the study was not focused on the broad category of "green jobs," but rather jobs involved in the process of clean energy.

In remarks last week before signing several executive orders focused on his climate agenda, Biden tied his energy policy directly to his plans to rebuild the US economy, citing the need for new, green infrastructure that would generate millions of jobs.

"A key plank of our Build Back Better Recovery Plan is building a modern, resilient climate infrastructure," Biden said, "and clean energy future that will create millions of good-paying union jobs -- not 7, 8, 10, 12 dollars an hour, but prevailing wage and benefits."

During his campaign, Biden's climate agenda included the goal of creating 10 million new jobs related to clean energy on top of the 3 million clean energy jobs the campaign said currently exist. "If executed strategically, our response to climate change can create more than 10 million well-paying jobs in the United States," the plan says, without laying out a timeline for that jobs-creating goal.

It's certainly an ambitious goal. Measuring the feasibility of Biden's plan is quite difficult and depends on several variables, including whether Congress will pass climate legislation. Biden has proposed a $2 trillion climate plan, which includes spending on things such as green energy infrastructure overhaul across the US. Green jobs are also hard to define, with different studies varying widely on what type of jobs they choose to include. For context, it's also worth examining the climate and energy efforts of President Barack Obama, many of which were repealed under President Donald Trump, and the effect they had on green jobs.

Under the eight years of Obama's presidency, the US economy added 11.6 million total new jobs, which only adds to the steepness of Biden's challenge, if as he said during his campaign, he wants to create 10 million new clean energy jobs.

Clean energy job numbers

Measuring the feasibility of Biden's plan first requires establishing what these clean energy-related jobs are and getting good data to establish a baseline and historical trends, which isn't easy.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics studied what it called "green jobs" starting in 2010 before budget cuts stopped the study in 2013. The BLS defined these jobs broadly, in part as those "in which workers' duties involve making their establishment's production processes more environmentally friendly or use fewer natural resources."

This definition was not limited to those who directly contribute to building, installing or maintaining green energy technology but was so broad it included jobs in sewage, publishers of environmental trade publications and environment and science museums, to name a few.

In the survey for 2010, the BLS reported the US had "3.1 million green goods and services (GGS) jobs."

A 2020 report from Environmental Entrepreneurs, a non-partisan group of business leaders focused on environment and the economy, found that "[b]efore the COVID-19 crisis, nearly 3.4 million Americans worked in clean energy—solar, wind, energy efficiency, clean vehicles, and more."

Bob Keefe, executive director of Environmental Entrepreneurs, said the study was not focused on the broad category of "green jobs," but rather jobs involved in the process of clean energy.

"[P]eople can call whatever they want a green job," Keefe said, "whether it's somebody who works in recycling or something like that. OK, fine they are green jobs. I'm talking about clean energy jobs."

According to the report from Environmental Entrepreneurs, these clean energy jobs increased by about 2% in 2019 and 4% in 2018. But for Biden to reach just a million new clean energy jobs in his first four years, there would need to be a yearly increase of 6.7% based on the figures from the Environmental Entrepreneurs report, and that's after returning to pre-Covid levels of employment.

Obama's efforts

Obama, who campaigned heavily on addressing climate change, ran into significant roadblocks everywhere from the courts, legislation dying in the Senate and ultimately having many of his administration's new environmental regulations repealed under President Donald Trump.

Obama did pass the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in February 2009 to jumpstart the economy in the midst of the recession. The Recovery Act contained grants and loans for the EPA and Department of Energy.

One study led by Syracuse Professor David Popp examined the "green" funds from the Recovery act -- focused on environment-related issues -- and found that for every $1 million spent, 10 new jobs were created a few years later.

"Almost all of those jobs were in manual labor, a lot of them were construction," Popp told CNN. "A lot of that's by design because that's where the money was targeted" through energy efficiency renovations and installing renewable energy infrastructure.

Cap and trade legislation, which would have set limits on carbon dioxide emissions for companies, died in a Senate controlled by 57 Democrats -- seven more than Biden currently has -- after the House passed the bill in 2009.

"[Obama] had this one huge setback, and then he lost control of Congress," Adam Rome, an environmental historian at the University at Buffalo, told CNN.

Despite Democrats only controlling Congress by a razor thin margin, Rome said, Biden could have the opportunity to work toward "legislative, not executive action" to address climate change.

"Biden, I think, recognizes that he has the kind of New Deal moment here," Rome said.

Biden's challenge

Biden can't accomplish his vast, $2 trillion clean energy plan without action from Congress. Right now the President would need every Senate Democrat on board to pass any legislation needed -- and he may even need Republicans signing on too if Democrats like Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema continue to oppose eliminating the filibuster.

The current pandemic also creates limitations on what Biden can currently accomplish in Congress, with most members focused on a Covid-19 economic stimulus package. And if the President is unable to pass a stimulus package, it's extremely unlikely his climate agenda would.

Even if Biden passes his energy plan, through a Senate with strong disagreements over environmental policies, experts disagree on whether his goal of millions more clean energy jobs is attainable.

"If the question is, do I think that the Biden plans are going to create millions of jobs, the answer is yes," Keefe told CNN. "Is it 10 million? Is it 20 million? I think that's to be determined."

Keefe noted that some of these future jobs are already being planned, with General Motors announcing that by 2035 it would only be producing emission free vehicles.

Benjamin Zycher, a resident scholar focused on energy and environmental policy at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank, told CNN that "more expensive energy means less employment. It's just that simple."

"The best you could hope for," Zycher said, "is merely an employment shift out of other sectors into green sectors, however that's defined."

© Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) listens as Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill on December 20, 2020 in Washington, DC. A group of 120 Democrats have urged the leadership to repeal a Trump era tax cut that benefits millionaires.

© Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) listens as Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill on December 20, 2020 in Washington, DC. A group of 120 Democrats have urged the leadership to repeal a Trump era tax cut that benefits millionaires.