by Maritsa Georgiou

Friday, November 1st 2019

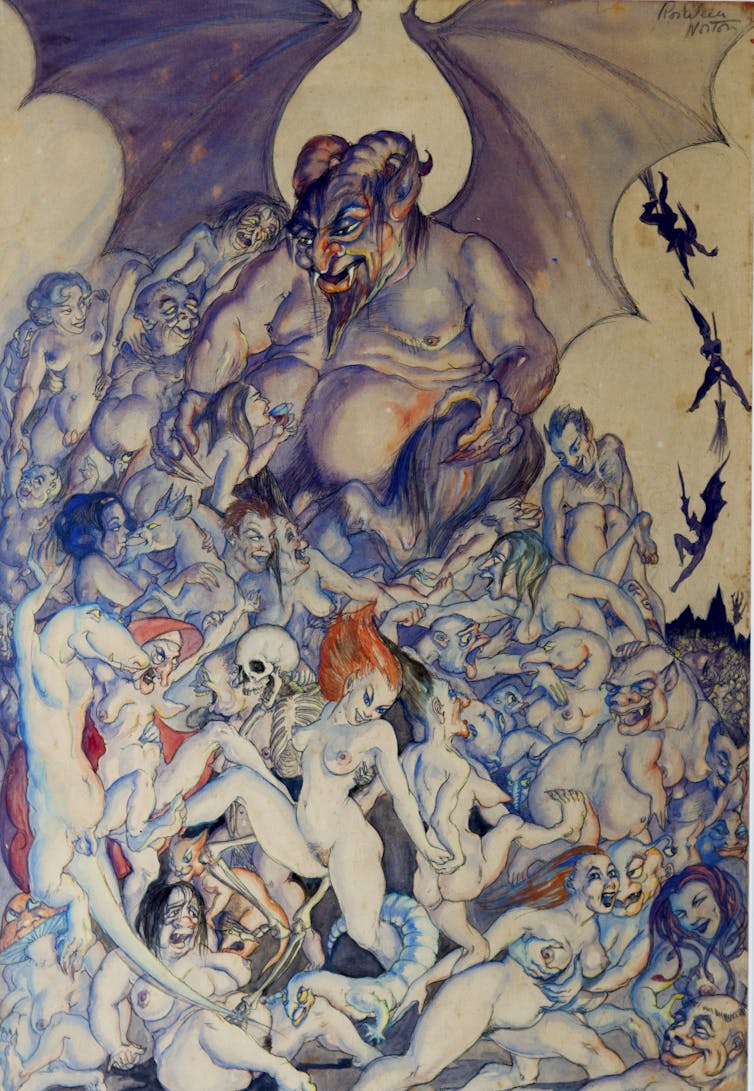

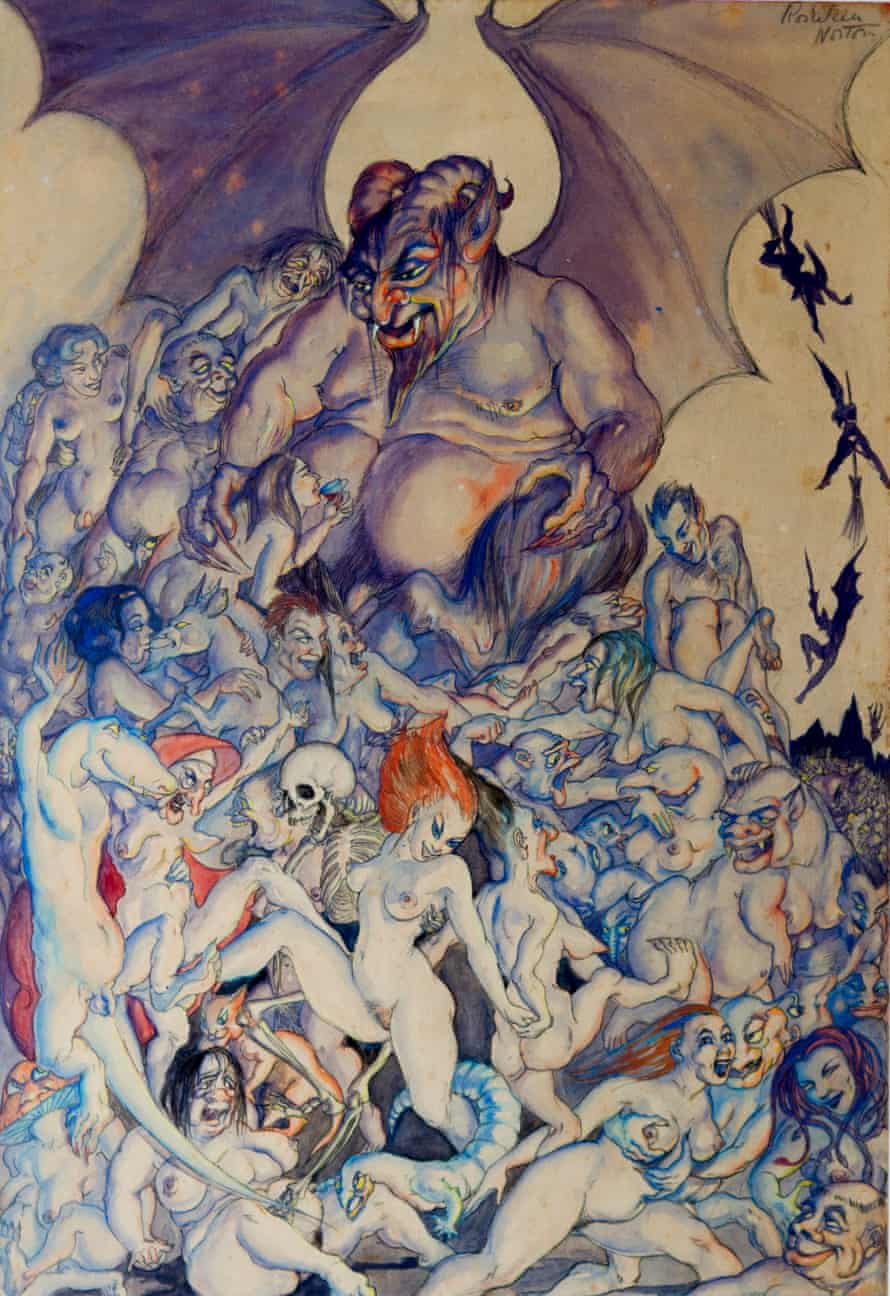

A Sasquatch warning sign hangs in the forest at the Montana Vortex, where several people have reported seeing Bigfoot. Photo: NBC Montana

COLUMBIA FALLS, Mont. — On any given day in a forest in the Pacific Northwest, you can find people searching for proof of a mysterious creature.

“Yes, I do believe in Bigfoot.” That’s what Joe Hauser told us on a late summer day at the Montana Vortex and House of Mystery outside Glacier National Park. GLACIER IS SHARED WITH CANADA, WE CALL IT WATERTON NATIONAL PARK, BIGFOOT IS A CANADIAN TOURIST FROM HARRISON, BC

Hauser walks the grounds every day. He bought the property to study the electromagnetic anomaly. He’s the first to tell you weird things happen there.

“A lot of people come in totally skeptical, and then they leave and go, ‘I don’t know what’s going on here, but there’s definitely something going on here,’” Hauser said.

And people like Hauser say they’ve seen Bigfoot appear out of nowhere in the very woods surrounding the Montana Vortex.

You can find Bigfoot reminders everywhere at the tourist attraction, including what believers say is real evidence of footprints.

“You can see they’re all different just like our feet are all different,” Hauser explained, showing off casts of the footprints. “That was from Bluff Creek by Roger Patterson -- and that’s where the Patty video was actually done in California.”

That Patty video is possibly the most controversial and known footage of what some say is Bigfoot. It was shot in 1967, and it’s what first piqued Hauser’s interest.

“I remember watching that on the news with my parents and grandparents -- and my grandfather and dad and uncle, they had an experience in Colorado where they found large tracks in the 1930s.”

Hauser’s first encounter took place goldmining in California in 1983.

“We heard some really big loud screams and whoops. It was like a howler monkey on steroids. And I turned to my partner and said, ‘What the heck is that?’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s Bigfoot. Haven’t you heard him yet?’”

It took 22 more years before Hauser says he actually saw a Sasquatch -- at the ever popular Avalanche Lake in Glacier Park with his son.

“He looks across the lake and goes, ‘Hey Dad, there’s two Bigfoot walking across that snow field there.’ And sure enough -- big strides, great big arm swings, arms down to their knees. And we had about a 5-minute sighting walking across the snow field.”

Hauser’s most recent sighting took place last fall on a trail at the Vortex, where tourists also reported seeing them. Hauser says Bigfoot will knock on his house at night and leave signs on his walkways after he's raked them.

Joe Hauser, Bigfoot enthusiast and Montana Vortex owner, talks everything Sasquatch with Maritsa Georgiou.{https://nbcmontana.com/news/local/mythical-or-mysterious-search-for-bigfoot-alive-among-montana-believers }

A Sasquatch warning sign hangs in the forest at the Montana Vortex, where several people have reported seeing Bigfoot. Photo: NBC Montana

COLUMBIA FALLS, Mont. — On any given day in a forest in the Pacific Northwest, you can find people searching for proof of a mysterious creature.

“Yes, I do believe in Bigfoot.” That’s what Joe Hauser told us on a late summer day at the Montana Vortex and House of Mystery outside Glacier National Park. GLACIER IS SHARED WITH CANADA, WE CALL IT WATERTON NATIONAL PARK, BIGFOOT IS A CANADIAN TOURIST FROM HARRISON, BC

Hauser walks the grounds every day. He bought the property to study the electromagnetic anomaly. He’s the first to tell you weird things happen there.

“A lot of people come in totally skeptical, and then they leave and go, ‘I don’t know what’s going on here, but there’s definitely something going on here,’” Hauser said.

And people like Hauser say they’ve seen Bigfoot appear out of nowhere in the very woods surrounding the Montana Vortex.

You can find Bigfoot reminders everywhere at the tourist attraction, including what believers say is real evidence of footprints.

“You can see they’re all different just like our feet are all different,” Hauser explained, showing off casts of the footprints. “That was from Bluff Creek by Roger Patterson -- and that’s where the Patty video was actually done in California.”

That Patty video is possibly the most controversial and known footage of what some say is Bigfoot. It was shot in 1967, and it’s what first piqued Hauser’s interest.

“I remember watching that on the news with my parents and grandparents -- and my grandfather and dad and uncle, they had an experience in Colorado where they found large tracks in the 1930s.”

Hauser’s first encounter took place goldmining in California in 1983.

“We heard some really big loud screams and whoops. It was like a howler monkey on steroids. And I turned to my partner and said, ‘What the heck is that?’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s Bigfoot. Haven’t you heard him yet?’”

It took 22 more years before Hauser says he actually saw a Sasquatch -- at the ever popular Avalanche Lake in Glacier Park with his son.

“He looks across the lake and goes, ‘Hey Dad, there’s two Bigfoot walking across that snow field there.’ And sure enough -- big strides, great big arm swings, arms down to their knees. And we had about a 5-minute sighting walking across the snow field.”

Hauser’s most recent sighting took place last fall on a trail at the Vortex, where tourists also reported seeing them. Hauser says Bigfoot will knock on his house at night and leave signs on his walkways after he's raked them.

Joe Hauser, Bigfoot enthusiast and Montana Vortex owner, talks everything Sasquatch with Maritsa Georgiou.{https://nbcmontana.com/news/local/mythical-or-mysterious-search-for-bigfoot-alive-among-montana-believers }

And he's not alone.

“Most people don’t talk about it, because there’s kind of a stigma to it, and people think you’re crazy because you saw a Bigfoot or you heard something,” Hauser said.

But some people do talk about it. You can find thousands of reports on the Bigfoot Field Research Organization website, which is run by reality show personality Matt Moneymaker of “Finding Bigfoot” fame. It includes photos and audio recordings and descriptions of sightings, including hundreds of Montana sightings from Missoula to Malta.

The BFRO has collected reports since 1995. Once you report a sighting, a BFRO investigator will likely do a follow-up report. The database shows 22 of Montana's 56 counties don't have any sightings. Missoula County has the most official reports to the BFRO at 17. Flathead comes in second with 13, and Gallatin County ranks third with 10 reports. But there are many more sightings you won’t find on the site.

“We have lots of sightings here; they’re just not reported,” Hauser said. “We take reports in here almost every week. And this is all over Montana. Georgetown Lake, Anaconda, and people have been having experiences down there for years. Glacier Park has a lot of sightings up there.”

There's no doubt Bigfoot has made a comeback in pop culture. Montana filmmaker Adam Pitman wrote his first screenplay in 1999, a psychological thriller about Bigfoot. It came after his dad recounted a strange sighting.

“He was on a jog, and up ahead of him this guy walked out across the road, but it wasn’t a guy,” Pitman said. “He was much taller, pure black and long arms. Very long arms that reached down to his knees.”

Pitman researched the legend at length, but added, “I’m not a believer. No. I’ve heard countless stories, but I want to see. And during my research I’ve gone through so many pictures and so many stories and nothing is definitive or caught me, like, how could that be explained?”

“There’s thousands of sightings and people are hearing whoops and screams and stuff like that,” Hauser said. “So we either have thousands of delusional liars out there, or something is really going on.”

So where's the evidence?

“There’s been bones that have been found; there’s been DNA studies that have been done,” Hauser explained. “There’s another DNA study being done right now.”

He couldn’t comment on the studies, but said they’re being done at reputable universities. He says some of that DNA was collected at his Vortex.

“They like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and if you put double-faced tape on the outside and they pick up the bowl it leaves hair and skin follicles,” Hauser said. “And then if you put a different variety of food in there, they’ll sample it. They don’t like Skittles or M&Ms, so they’ll put it in their mouth and then spit it back out in the bowl, and there’s saliva. There are DNA tests being done right now.”

Until those test results come back, the questions remain.

“All of those out there searching for Bigfoot, good luck,” Pitman said, addressing the camera. “Find him. I want to believe!”

“If you ever have a Bigfoot experience, once you have that experience it changes your life,” Hauser said.

And with every experience, the legend lives on, and so do the searches through our Montana forests.

Even in the camp of believers, there are a lot of debates on topics like why the creatures are so elusive and so on.

Hauser says there’s been an increase in scientific interest in recent years, and he hopes more evidence comes out of that.