MAOIST CULTURAL REVOLUTION REDUX

If the others go I'll go': Inside China's scheme to transfer Uighurs into work

By John Sudworth

BBC News, Beijing

China's policy of transferring hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang to new jobs often far from home is leading to a thinning out of their populations, according to a high-level Chinese study seen by the BBC.

The government denies that it is attempting to alter the demographics of its far-western region and says the job transfers are designed to raise incomes and alleviate chronic rural unemployment and poverty.

But our evidence suggests that - alongside the re-education camps built across Xinjiang in recent years - the policy involves a high risk of coercion and is similarly designed to assimilate minorities by changing their lifestyles and thinking.

The study, which was meant for the eyes of senior officials but accidentally placed online, forms part of a BBC investigation based on propaganda reports, interviews, and visits to factories across China.

And we ask questions about the possible connections between transferred Uighur labour and two major western brands, as international concern mounts over the extent to which it is already ingrained in global supply chains.

In a village in southern Xinjiang, hay is being gathered in the fields and families are placing fruit and flatbreads on their supas, the low platforms around which Uighur family life has traditionally revolved.

But the warm wind blowing across the Taklamakan desert is bringing with it worry and change.

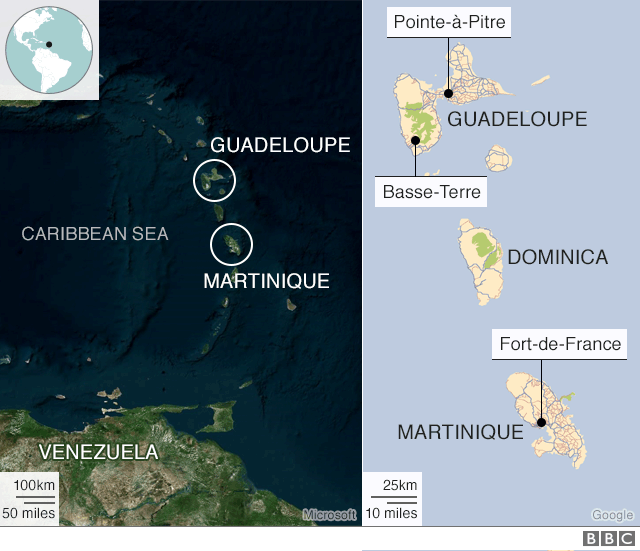

The video report, broadcast by China's Communist Party-run news channel, shows a group of officials in the centre of the village, sitting under a red banner advertising jobs in Anhui Province, 4,000km away.

After two full days, the reporter's narration says, not a single person from the village has come forward to sign up, and so the officials begin moving from house to house.

What follows is some of the most compelling footage of China's massive campaign to transfer Uighurs, Kazakhs and other minorities in Xinjiang into factory and manual labouring jobs, often considerable distances from their homes.

A 2017 TV report from China's state broadcaster illustrates how the policy works in practiceAlthough it was broadcast in 2017, around the time the policy began to be intensified, the video has not featured in international news reporting until now.

The officials speak to one father who is clearly reluctant to send his daughter, Buzaynap, so far away.

"There must be someone else who'd like to go," he tries to plead. "We can make our living here, let us live a life like this."

They speak directly to 19-year old Buzaynap, telling her that, if she stays she will be married soon and never able to leave.

"Have a think, will you go?" they ask.

Under the intense scrutiny of the government officials and state-TV journalists she shakes her head and replies, "I won't go."

Still, the pressure continues until eventually, weeping, she concedes.

"I'll go if others go," she says.

The film ends with tearful goodbyes between mothers and daughters as Buzaynap and other similarly "mobilised" recruits leave their family and culture behind.

Professor Laura Murphy is an expert in human rights and contemporary slavery at the UK's Sheffield Hallam University who lived in Xinjiang between 2004 and 2005 and has visited since.

"This video is remarkable," she told the BBC.

"The Chinese government continually says that people are volunteering to engage in these programmes, but this absolutely reveals that this is a system of coercion that people are not allowed to resist."

"The other thing it shows is this ulterior motive," she said, "that although the narrative is one of lifting people out of poverty, there's a drive to entirely change people's lives, to separate families, disperse the population, change their language, their culture, their family structures, which is more likely to increase poverty than to decrease it."

A marked shift in China's approach to its governance of Xinjiang can be traced back to two brutal attacks on pedestrians and commuters - in Beijing in 2013 and the city of Kunming in 2014 - which it blamed on Uighur Islamists and separatists.

At the heart of its response - in both the camps and the work transfer schemes - has been a drive to replace "old" Uighur loyalties to culture and the Islamic faith with a "modern" materialist identity and an enforced allegiance to the Communist Party.

This overarching goal of assimilating Uighurs into China's majority Han culture is made clear by an in-depth Chinese study of Xinjiang's job-transfer scheme, circulated to senior Chinese officials and seen by the BBC.

Based on field work conducted in Xinjiang's Hotan Prefecture in May 2018, the report was inadvertently made publicly available online in December 2019 and then subsequently taken down a few months later.

Written by a group of academics from Nankai University in the Chinese city of Tianjin, it concludes that the mass labour transfers are "an important method to influence, meld and assimilate Uighur minorities" and bring about a "transformation of their thinking."

Uprooting them and relocating them elsewhere in the region or in other Chinese provinces, it says, "reduces Uighur population density."

The report was discovered online by a Uighur researcher based overseas and an archived version (Chinese) was saved before the university realized its error.

Dr Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, has written his own analysis of the report which includes an English translation of it.

"This is an unprecedented, authoritative source written by leading academics and former government officials with high-level access to Xinjiang itself," Dr Zenz said in a BBC interview.

"The excess surplus population that somehow has to be dealt with, and labour transfers as a means to reduce the concentration of those workers in their own heartlands is, in my opinion, the most stunning admission of this report."

His analysis includes a legal opinion from Erin Farrell Rosenberg, a former senior advisor to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, that the Nankai Report provides "credible grounds" for the crimes against humanity of forcible transfer and persecution.

In a written statement, the Chinese foreign ministry said, "The report reflects only the author's personal view and much of its contents are not in line with the facts."

"We hope that journalists will use the authoritative information released by the Chinese government as the basis for reporting on Xinjiang."

The Nankai report authors write glowingly of an effort to combat poverty underwritten by a "guarantee of voluntariness" in the work placements, and with the factories allowing the workers to "leave and return freely."

But those claims are somewhat at odds with the level of detail they provide about the way the policy works in practice.

There are "targets" to be reached, with Hotan Prefecture alone - at the time the study was undertaken - having already exported 250,000 workers, one fifth of its total working age population.

There is pressure to meet the targets, with recruiting stations set up "in every village" and officials tasked to "mobilize collectively" and "visit households," just as in 19-year-old Buzaynap's case.

And there are signs of control at every stage, with all recruits put through "political thought education," then transported to the factories in groups - sometimes as many as hundreds at a time - and "led and accompanied by political cadres in order to implement security and management."

Farmers unwilling to leave their lands or herds behind are encouraged to transfer them to a centralized government scheme that manages them in their absence.

And once they arrive in their new factory jobs, workers themselves are put under the "centralized management" of officials who "eat and live" with them.

But the report also notes that the profound discrimination at the heart of the system is getting in the way of its effective functioning, with local police forces in eastern China so alarmed by the arrival of trainloads of Uighurs, that they are sometimes turned back.

In places, it even warns that China's policies in Xinjiang may have been too extreme, for example, stating that the number of people placed in the re-education camps "far exceeds" those with suspected connections to extremism.

"The entire Uighur population should not be assumed to be rioters," it says.

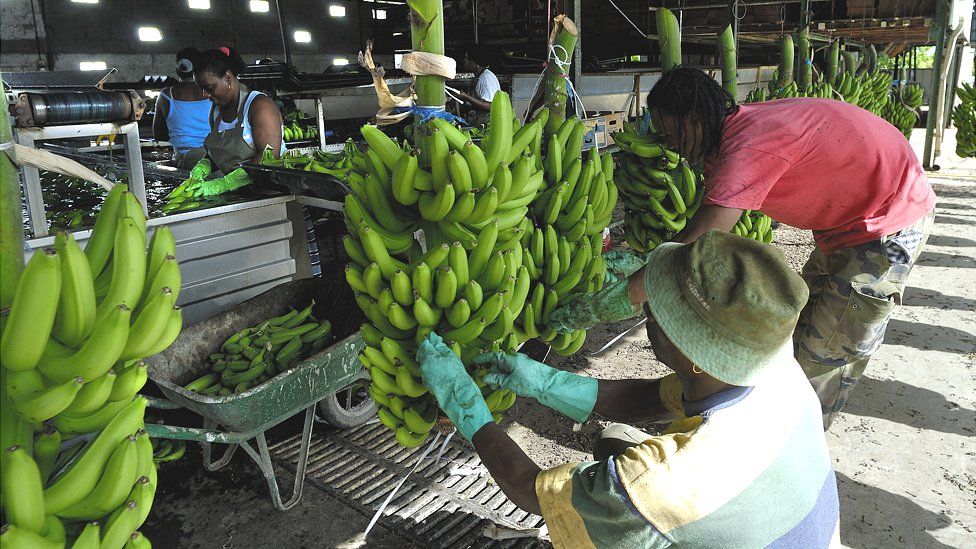

The Huafu Textile Company is located on the edge of a grey industrial estate in the city of Huaibei, in China's eastern province of Anhui.

It was to this factory that Buzaynap, featured in the state-TV report, was sent.

When the BBC visited, the separate, five-story Uighur dormitory showed few signs of habitation apart from a pair of shoes placed by an open window.

At the gate, the security guard said that the Uighur workers "have gone back home," adding that it was because of the country's Covid controls, and in a statement Huafu told us that, "the company does not currently employ Xinjiang workers."

The BBC was able to find pillowcases made with Huafu yarn on sale on Amazon's UK website, although it is not possible to confirm if the product is linked to the particular factory we visited, or one of the company's other facilities.

Amazon told the BBC that it does not tolerate the use of forced labour and that where it finds products that do not meet its supply chain standards, it removes them from sale.

The BBC worked with a group of international journalists based in China, visiting a total of six factories between us.

At the Dongguan Luzhou Shoes factory in Guangzhou Province, one worker said the Uighur employees used separate dormitories and their own canteen, and another local told reporters that the company makes shoes for Skechers.

The factory has previously been linked to the US company, with unverified social media videos purportedly showing Uighur workers making Skechers product lines, and references to a relationship in online Chinese business directories.

In a statement, Skechers said it had "zero tolerance for forced labour," but did not answer questions about whether it used Dongguan Luzhou as a supplier.

Dongguan Luzhou did not respond to a request for comment.

Interviews recorded at the scene suggest the Uighur workers were free to leave the factory during their leisure time, but at other factories visited for the research, the evidence was more mixed.

In at least two cases, reporters were told of some restrictions, and at one facility in the city of Wuhan a Han Chinese employee told the BBC that his 200 or so Uighur colleagues were not allowed out at all.

Three months after Buzaynap was shown leaving her village to begin her political education training, the Chinese state-TV crew meet her again, this time in the Huafu Textile Company in Anhui.

The theme of assimilation is, once again, central to the news report.

In one scene, Buzaynap is close to tears as she is scolded for her mistakes, but eventually, a transformation is said to be taking place.

"The timid girl who didn't speak and kept her head down," we are told, "is gaining authority at work."

"Lifestyles are changing and thoughts are changing."

Producer: Kathy Long

© Provided by Refinery29

© Provided by Refinery29