Why We Need Stuart Hall’s Imaginative Left

Why We Need Stuart Hall’s Imaginative Left.

Why We Need Stuart Hall’s Imaginative Left.

A pioneer of cultural studies, Hall showed a generation how to meld identity and Marxism.

April 3, 2021

Jessica Loudis

THE NEW REPUBLIC

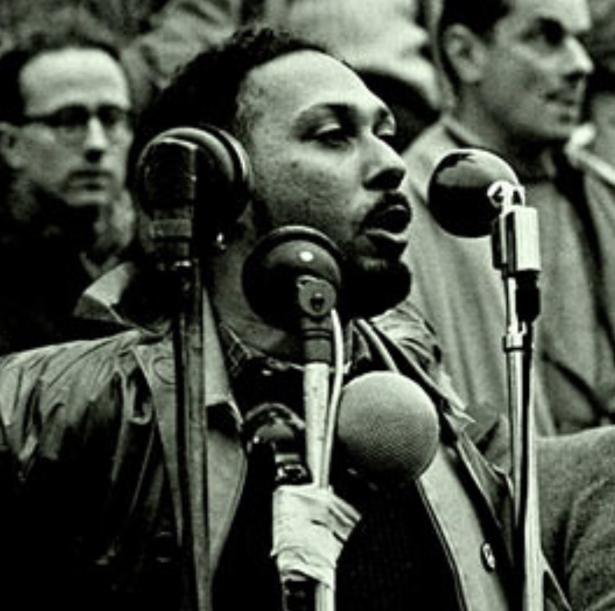

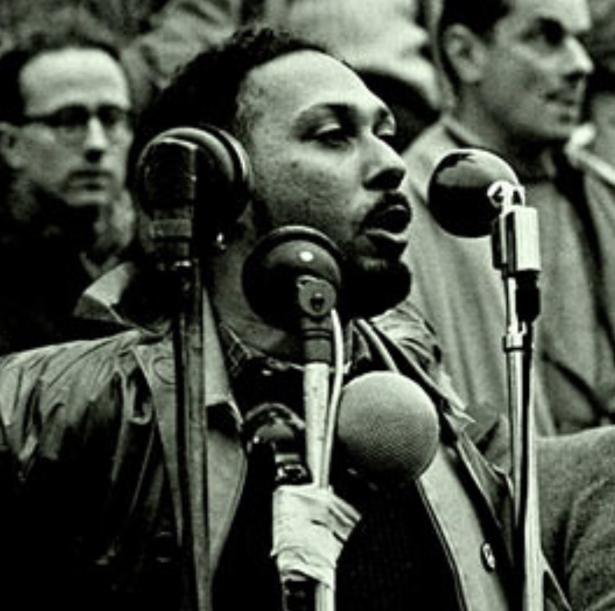

Stuart Hall, The Open University (OU) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When Stuart Hall died in 2014, he was one of England’s best-known intellectuals, celebrated for his pioneering writings in cultural studies, a field he helped invent along with Raymond Williams, and for his work as a spokesman of the New Left. Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. described him as “the Du Bois of Britain,” and The Guardian called himthe “godfather of multiculturalism.” During the six decades he lived in England, Hall appeared regularly on TV and radio (including on his own BBC series about the history of the Caribbean), popularized the term “Thatcherism,” co-wrote an influential book on race and policing, and helped found The New Left Review.

Hall took a more expansive view of popular culture than the previous generations of British leftists, who tended to deride it as a monolithic means by which the working-classes were subjected to upper-class hegemony. He saw pop culture as a field of struggle, which held the potential to bring about positive change, rather than simply oppression. As his thinking evolved, he came to insist on a larger vision of politics, one that ventured beyond traditional actors and institutions into more subjective realms. Politics, he argued, was not simply a matter of elections: Politics was everywhere, present in everything from soccer games to soap operas. “The conditions of existence,” he once remarked in an interview are “cultural, political and economic”—in that order.

Despite this reputation, Hall’s legacy was far from assured by the time he died. By 2014, his only single-author book had fallen out of print, and his essays were scattered across obscure journals and anthologies. In the London Review of Books, Terry Eagleton admonished Hall for his “frenetic recycling of theories in the realm of culture,” calling him “less an original thinker than a brilliant bricoleur, an imaginative reinventor of other people’s ideas.” Only recently have American publishers attempted to revive his legacy. Duke has launched a book series dedicated to his collected writings, edited by Catherine Hall and Bill Schwarz, as well as publishing a collection of essays by David Scott, a cultural anthropologist at Columbia who is working on a biography of Hall. Harvard is publishing a trifecta of lectures Hall delivered at the university in 1994 as The Fateful Triangle; MIT is releasing an anthology of essays about his work, and Routledge is putting out a conversation between Hall and bell hooks.

These efforts are well-timed: Hall’s work has become especially resonant as Britain has voted for a narrower identity and a more isolationist attitude to the rest of the world. Because of his own ancestry as “part Scottish, part African, part Portuguese-Jew,” Hall always saw identity as pluralistic, and rejected the notion that a person was strictly “English” or “Jamaican.” Towards the end of his life, Hall came to believe that the intransigence of cultural differences would not be able to mesh neatly with the government and conservative media’s increasing demands for “Britishness.” This was partly because of the “regressive modernization” Hall saw under Thatcher—which has echoes in Brexit and Donald Trump—but also because of the imaginative failure on the other side of the political divide; the way the left simply accepted a conservative vision of the world as the consensus on reality.

Hall was born in Jamaica in 1932 into the “brown middle class,” the child of a United Fruit worker and a light-skinned mother. His mother, whose family had once been wealthy, idealized the estate days of colonialism and prevented her son from playing with children she considered beneath them. As the darkest member of a family that insulated itself from the world of “black Jamaica,” Hall became, he writes, increasingly alienated at home and gravitated towards “the less-colour hierarchical Jamaica that was emerging.” Although independence was still decades away, Hall came of age at a time of burgeoning anti-imperialism. During his first term in high school, an older boy was suspended for throwing a book at a colonialist history teacher. That boy, Michael Manley, went on to become head of the leftist People’s National Party and, eventually, prime minister.

In 1951, Hall left Kingston for a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford. It was his first trip to England, and despite having grown up in the shadow of British Empire, he was struck by how “impenetrably English” everything seemed, how behavior was guided by a matrix of unwritten rules and social codes. Several days later, Hall’s conception of England was challenged when, passing by Paddington Station, he saw “a stream of black people spilling out into the London afternoon”—his first encounter with the Caribbean diaspora, which began arriving in England three years earlier on the SS Empire Windrush. He recalled the moment in his autobiography, Familiar Stranger:

It is hard to reconstruct the effect of seeing these black West Indian working men and women in London, with their strapped-up suitcases and bulging straw baskets, looking for all the world as if they planned a long stay. They had made extraordinary efforts within their means to dress up to the nines for the journey, as West Indians always did in those days when traveling or going to church: the men in soft-brim felt hats, cocked at a rakish angle, the women in flimsy, colourful cotton dresses, stepping uncertainly into the wind, or waiting for relatives or friends to rescue them from the enveloping strangeness. They hesitated in front of ticket windows, trying to figure out how to take another train to some equally unfamiliar place, to find people they knew who had preceded them.

As Hall would later say in interviews, he arrived in England when it was transitioning from “a class society to a mass society”: a moment marked by the influx of immigrants, the breakup of so-called “traditional” culture in favor of Americanization, and the rise of socially conservative, free-market politics.

At Oxford, that bastion of Englishness, Hall ran with the foreign students (excluding V.S. Naipaul, whom he remembers as a snob), and, though he initially aspired to be a novelist, became increasingly invested in “Third World” liberation politics. The literature department at the time was grappling with the legacy of F.R. Leavis, whose journal Scrutiny revolutionized criticism by applying it, disdainfully, to mass culture. Hall gravitated towards the Marxist scholars taking aim at Leavis’s belief that only great English novelists could save civilization from the so-called barbarians. The young critic read Raymond Williams and studied with Richard Hoggart, whose revolutionary Uses of Literacy would soon apply a literary-sociological lens to British working-class culture. At the same time, Hall began taking regular trips to London, staying with the “bearded radicals” his parents had warned him about.

Despite misgivings, Hall was on course to earn a place within the British literary establishment. He completed his undergraduate degree and started writing a doctoral thesis on Henry James, uncertain where this endeavor would lead him. Then, 1956 upended everything. As Russia invaded Hungary to crush a nascent revolution, and Britain and France invaded Egypt to stop the nationalization of the Suez Canal, Hall abandoned his thesis to become a part-time teacher and activist. While he had never been a fully committed Marxist, the events of that year, he would later write, “brought to an end a certain kind of socialist innocence.”

Out of this rude awakening, the New Left was born. The following year, as Ghana declared its independence, Hall founded a magazine called Universities and Left Review, which three years later would combine with The New Reasoner to form the New Left Review. In the interim, he set up and ran the Partisan Café in London to help fund the publication. The coffee bar became a favorite hangout for the anti-Stalinist left, attracting hundreds to its weekly meetings, including Eric Hobsbawm, Karel Reisz, Doris Lessing, John Berger, and undercover members of the police. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament also grew out of these gatherings, and Hall’s speeches for the organization helped solidify his reputation as an activist and public intellectual. Eight years later, he was recruited by Hoggart to help run the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

While Hall’s political commitments were established by the time he left Oxford, his intellectual methodology was forever shifting, moving from political sociology to media theory to structuralism—whatever proved most useful in unpacking the materials mass culture served up. Hall first gained recognition as a media theorist for his innovative work on reception theory, which analyzed how a reader’s background and experiences influenced their reading of a text. His thinking was revolutionized in the 1970s, however, when Frankfurt School and key continental European thinkers were translated into English. Suddenly, through their willingness to read politics through the lenses of institutions and popular culture, Adorno and Althusser offered new tools with which to understand the changing political climate of Britain.

Antonio Gramsci, the early twentieth-century Italian political theorist, proved especially influential. From him, Hall borrowed the notion of “conjunctures”—periods in which “different social, political, economic and ideological contradictions” come together to form distinctive historical moments. This idea would form the basis of Hall’s early approach to politics. The post-WWII consensus, in which Western Europe countries embraced cradle-to-grave welfare programs, was one such conjuncture; the rise of Thatcherism, as Hall would demonstrate, was another. Against those willing to subordinate history to sweeping global theories, Hall emphasized the distinctiveness of specific moments.

While Hall occasionally draws heavily on jargon, there is a generosity and literary imagination in his writing—a recognition that humans are complex, contradictory creatures shaped by, among other things, what they believe, where they live, how they shop, and who they sleep with. As a foreigner and a black man in England, Hall refused pious or reductionist interpretations of politics, such as dogmatic Marxism, which failed to account for people like him.

This is evident in his political essays, but it is conveyed more explicitly in a series of lectures he delivered at the University of Urbana-Champaign in the summer of 1983, recently reissued by Duke as Cultural Studies 1983, which would become the theoretical basis for the field. The lectures construct an analytic framework through borrowing from, and occasionally discarding, the ideas of Hoggart, Leavis, Durkheim, and Levi-Strauss, as well as Althusser and Gramsci. In these talks, we see Hall questioning Marxist orthodoxy, and grasping beyond it:

I wonder how it is that all the people I know are absolutely convinced they are not in false consciousness, but can tell at the drop of a hat that everybody else is. I have never understood how anybody can advance in the field of political organization and struggle by ascribing an absolute distinction between those who can see through transparent surfaces, through the complexity of social relations… Indeed, I have always undertaken to move from the opposite position, assuming that all ideologies which have ever organized men and women organically have something true about them.

Hall characterized ideology as the frameworks with which people translate and interpret society, and he saw them functioning all around him—on TV and in pubs, in classrooms and cinemas, and especially in media. As historian Frank Mort notes, while reading culture as political was groundbreaking at the time, it did draw on a history of left-leaning sociological work in Britain. (Accordingly, Hall once remarked that he wanted “to do sociology better than the sociologists.”) From the 1930s to the mid-60s, the Mass Observation movement aimed to chronicle the “everyday lives” of British people, and in the 1950s the Institute of Community Studies mapped the family structures of low-income communities in London. The Institute eventually spawned the Open University, where Hall taught for 18 years after leaving Birmingham.

By the mid-‘60s, Hall had married Catherine Barrett, a British feminist historian whose work would deeply influence his own, and had co-written The Popular Arts, one of the first books to apply serious analysis to popular film. At that point, the couple was living in the industrial English city, which, as James Vernon observes in an excellent essay on Hall and race, was riven by racial tensions. The year they moved there, Vernon writes, a “Conservative Party candidate ran an election campaign on the slogan ‘If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.’ ” Three years later, in 1968, conservative MP Enoch Powell would deliver his infamous “rivers of blood” speech in Birmingham, suggesting that a flood of immigrants would result in just that. That same year, Catherine gave birth to their daughter, the first of two children.

The late ‘60s and early ‘70s in England saw the rise of left-wing social movements, namely black power and feminism, which Catherine participated in by starting Birmingham’s first women’s liberation group. It was also the era of screaming headlines about crime and the so-called “Sus” laws, which gave police carte blanche to stop and harass “suspicious” young (black) men. This set the stage for Hall’s breakthrough work, which applied a zoom lens to the conflicted national mood. InPolicing the Crisis, Hall and his co-authors examined the explosion of news reports about the rise of “muggings” in the UK, arguing that this trend captured a moral panic about outsiders and immigrants, and generally reflected a feeling of decline as England, struggling with unemployment and an inefficient welfare state, transitioned away from a social democratic order.

Hall’s analysis, which elaborated on his earlier media studies work, was among the first to identify journalistic fearmongering and openness to austerity as the factors that would bring radical conservatives to power. In the final sentence, he predicted the continued ascent of Margaret Thatcher. Unfortunately, he was right. In 1979, the year after Crisis was published, Thatcher was elected Prime Minister.

Thatcher’s victory marked the beginning of a new historical moment. Elected by lower- and middle-class voters following England’s “winter of discontent,” Thatcher took aim at trade unions, entitlement programs, and nationalized industries—gutting the Keynesian public policy that had propped up the country for more than three decades. In its place, she offered what Hall later described as a “a deeply rooted, closed conservatism around a tiny myth of a nation with a homogenous culture… coupled with a rabid short-term individualism that is tied to the market place.”

In Thatcherism, Hall found the case study that would consume much of his work and, ironically, exemplify the kind of cultural politics he had hoped to activate on the left. His essay “The Great Moving Right Show,” written in 1979, was an attempt to dissect the phenomenon and its traction among voters. To Hall, Thatcherism reflected what Gramsci called an “organic” crisis: a moment when people cease to trust political leaders and parties, and upstart forces challenge those seeking to conserve the old order. During these periods, contradictions arise that band together disparate groups, and the very idea of what is considered “ordinary common sense” changes. Thatcher did not succeed by tricking voters, Hall posits, but rather by constructing a worldview that mapped onto their real lives and problems (if not their class identities) and advancing policies that reflected those concerns. He takes this as a reminder that “interests are not given but always have to be politically and ideologically constructed.” Hall would spend the rest of his life criticizing Thatcher, but he did credit the ingenuity of her tactics.

As the ‘80s advanced, the children of the Windrush generation took to the streets to protest the structural racism that their parents had endured in silence, and Hall turned his attention to the left’s failure in the face of Thatcherism. In his riveting 1987 essay “Gramsci and Us,” Hall blamed the Labour Party for its administrative understanding of politics, and its belief that political subjects are one-dimensional actors whose motivations can be reduced to economic interests. That year in Britain, there was no shortage of crises. Thatcher was reelected, race riots broke out in Leeds, and one person a day was dying of AIDS. Yet the left, Hall wrote,

does not seem to have the slightest conception of what putting together a new historical project entails. It does not understand the necessarily contradictory nature of human subjects, of social identities. It does not understand politics as a production. It does not see that it is possible to connect with the ordinary feelings and experiences which people have in their everyday lives, and yet to articulate them progressively to a more advanced, modern form of social consciousness. … It does not recognize that the identities which people carry in their heads—their subjectivities, their cultural life, their sexual life, their family life and their ethnic identities, are always incomplete and have become massively politicized.

Thatcher’s reality was now Britain’s, and party politics offered no answers. In light of this, Hall focused his attention on the “identities which people carry around in their heads.” Culture was now the main turf of politics, and individual identities were being negotiated on this turf. The left, despite its claims to inclusivity and social justice, had failed to provide a vocabulary that was human and specific enough for people to recognize themselves in.

Meanwhile, across England younger generations of black and Asian artists were discovering Hall’s work. This included Isaac Julien, Keith Piper, and other visual artists and filmmakers who would eventually form the British Black Arts Movement. John Akomfrah, a filmmaker whose archival documentary The Stuart Hall Project (2013) rivals Raoul Peck’s I am Not Your Negro in its intellectual and emotional depth, was among them. Describing Hall’s allure in Stuart Hall: Conversations, Projects, Legacies, Akomfrah wrote that “for a group of young people who had gone from coloured to black… and many other derogatory epithets in between in their very short lives,” Hall’s ability to move fluidly between identities, subjects and theoretical positions was precisely the appeal. In the last decades of his life, Hall became the founding chair of Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) and the photography organization Autograph ABP, both of which named their libraries in his honor, and he continued working with the British Film Institute, a relationship that extended back to the ‘60s.

Where organized politics had failed, art emerged as a way to access individual subjectivity. To see “how difference operates inside people’s heads,” Hall said in a 2007 interview, “you have to go to art, you have to go to culture—to where people imagine, where they fantasize, where they symbolize.”

Jessica Loudis is the editor of World Policy Journal.

Stuart Hall, The Open University (OU) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When Stuart Hall died in 2014, he was one of England’s best-known intellectuals, celebrated for his pioneering writings in cultural studies, a field he helped invent along with Raymond Williams, and for his work as a spokesman of the New Left. Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. described him as “the Du Bois of Britain,” and The Guardian called himthe “godfather of multiculturalism.” During the six decades he lived in England, Hall appeared regularly on TV and radio (including on his own BBC series about the history of the Caribbean), popularized the term “Thatcherism,” co-wrote an influential book on race and policing, and helped found The New Left Review.

Hall took a more expansive view of popular culture than the previous generations of British leftists, who tended to deride it as a monolithic means by which the working-classes were subjected to upper-class hegemony. He saw pop culture as a field of struggle, which held the potential to bring about positive change, rather than simply oppression. As his thinking evolved, he came to insist on a larger vision of politics, one that ventured beyond traditional actors and institutions into more subjective realms. Politics, he argued, was not simply a matter of elections: Politics was everywhere, present in everything from soccer games to soap operas. “The conditions of existence,” he once remarked in an interview are “cultural, political and economic”—in that order.

Despite this reputation, Hall’s legacy was far from assured by the time he died. By 2014, his only single-author book had fallen out of print, and his essays were scattered across obscure journals and anthologies. In the London Review of Books, Terry Eagleton admonished Hall for his “frenetic recycling of theories in the realm of culture,” calling him “less an original thinker than a brilliant bricoleur, an imaginative reinventor of other people’s ideas.” Only recently have American publishers attempted to revive his legacy. Duke has launched a book series dedicated to his collected writings, edited by Catherine Hall and Bill Schwarz, as well as publishing a collection of essays by David Scott, a cultural anthropologist at Columbia who is working on a biography of Hall. Harvard is publishing a trifecta of lectures Hall delivered at the university in 1994 as The Fateful Triangle; MIT is releasing an anthology of essays about his work, and Routledge is putting out a conversation between Hall and bell hooks.

These efforts are well-timed: Hall’s work has become especially resonant as Britain has voted for a narrower identity and a more isolationist attitude to the rest of the world. Because of his own ancestry as “part Scottish, part African, part Portuguese-Jew,” Hall always saw identity as pluralistic, and rejected the notion that a person was strictly “English” or “Jamaican.” Towards the end of his life, Hall came to believe that the intransigence of cultural differences would not be able to mesh neatly with the government and conservative media’s increasing demands for “Britishness.” This was partly because of the “regressive modernization” Hall saw under Thatcher—which has echoes in Brexit and Donald Trump—but also because of the imaginative failure on the other side of the political divide; the way the left simply accepted a conservative vision of the world as the consensus on reality.

Hall was born in Jamaica in 1932 into the “brown middle class,” the child of a United Fruit worker and a light-skinned mother. His mother, whose family had once been wealthy, idealized the estate days of colonialism and prevented her son from playing with children she considered beneath them. As the darkest member of a family that insulated itself from the world of “black Jamaica,” Hall became, he writes, increasingly alienated at home and gravitated towards “the less-colour hierarchical Jamaica that was emerging.” Although independence was still decades away, Hall came of age at a time of burgeoning anti-imperialism. During his first term in high school, an older boy was suspended for throwing a book at a colonialist history teacher. That boy, Michael Manley, went on to become head of the leftist People’s National Party and, eventually, prime minister.

In 1951, Hall left Kingston for a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford. It was his first trip to England, and despite having grown up in the shadow of British Empire, he was struck by how “impenetrably English” everything seemed, how behavior was guided by a matrix of unwritten rules and social codes. Several days later, Hall’s conception of England was challenged when, passing by Paddington Station, he saw “a stream of black people spilling out into the London afternoon”—his first encounter with the Caribbean diaspora, which began arriving in England three years earlier on the SS Empire Windrush. He recalled the moment in his autobiography, Familiar Stranger:

It is hard to reconstruct the effect of seeing these black West Indian working men and women in London, with their strapped-up suitcases and bulging straw baskets, looking for all the world as if they planned a long stay. They had made extraordinary efforts within their means to dress up to the nines for the journey, as West Indians always did in those days when traveling or going to church: the men in soft-brim felt hats, cocked at a rakish angle, the women in flimsy, colourful cotton dresses, stepping uncertainly into the wind, or waiting for relatives or friends to rescue them from the enveloping strangeness. They hesitated in front of ticket windows, trying to figure out how to take another train to some equally unfamiliar place, to find people they knew who had preceded them.

As Hall would later say in interviews, he arrived in England when it was transitioning from “a class society to a mass society”: a moment marked by the influx of immigrants, the breakup of so-called “traditional” culture in favor of Americanization, and the rise of socially conservative, free-market politics.

At Oxford, that bastion of Englishness, Hall ran with the foreign students (excluding V.S. Naipaul, whom he remembers as a snob), and, though he initially aspired to be a novelist, became increasingly invested in “Third World” liberation politics. The literature department at the time was grappling with the legacy of F.R. Leavis, whose journal Scrutiny revolutionized criticism by applying it, disdainfully, to mass culture. Hall gravitated towards the Marxist scholars taking aim at Leavis’s belief that only great English novelists could save civilization from the so-called barbarians. The young critic read Raymond Williams and studied with Richard Hoggart, whose revolutionary Uses of Literacy would soon apply a literary-sociological lens to British working-class culture. At the same time, Hall began taking regular trips to London, staying with the “bearded radicals” his parents had warned him about.

Despite misgivings, Hall was on course to earn a place within the British literary establishment. He completed his undergraduate degree and started writing a doctoral thesis on Henry James, uncertain where this endeavor would lead him. Then, 1956 upended everything. As Russia invaded Hungary to crush a nascent revolution, and Britain and France invaded Egypt to stop the nationalization of the Suez Canal, Hall abandoned his thesis to become a part-time teacher and activist. While he had never been a fully committed Marxist, the events of that year, he would later write, “brought to an end a certain kind of socialist innocence.”

Out of this rude awakening, the New Left was born. The following year, as Ghana declared its independence, Hall founded a magazine called Universities and Left Review, which three years later would combine with The New Reasoner to form the New Left Review. In the interim, he set up and ran the Partisan Café in London to help fund the publication. The coffee bar became a favorite hangout for the anti-Stalinist left, attracting hundreds to its weekly meetings, including Eric Hobsbawm, Karel Reisz, Doris Lessing, John Berger, and undercover members of the police. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament also grew out of these gatherings, and Hall’s speeches for the organization helped solidify his reputation as an activist and public intellectual. Eight years later, he was recruited by Hoggart to help run the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

While Hall’s political commitments were established by the time he left Oxford, his intellectual methodology was forever shifting, moving from political sociology to media theory to structuralism—whatever proved most useful in unpacking the materials mass culture served up. Hall first gained recognition as a media theorist for his innovative work on reception theory, which analyzed how a reader’s background and experiences influenced their reading of a text. His thinking was revolutionized in the 1970s, however, when Frankfurt School and key continental European thinkers were translated into English. Suddenly, through their willingness to read politics through the lenses of institutions and popular culture, Adorno and Althusser offered new tools with which to understand the changing political climate of Britain.

Antonio Gramsci, the early twentieth-century Italian political theorist, proved especially influential. From him, Hall borrowed the notion of “conjunctures”—periods in which “different social, political, economic and ideological contradictions” come together to form distinctive historical moments. This idea would form the basis of Hall’s early approach to politics. The post-WWII consensus, in which Western Europe countries embraced cradle-to-grave welfare programs, was one such conjuncture; the rise of Thatcherism, as Hall would demonstrate, was another. Against those willing to subordinate history to sweeping global theories, Hall emphasized the distinctiveness of specific moments.

While Hall occasionally draws heavily on jargon, there is a generosity and literary imagination in his writing—a recognition that humans are complex, contradictory creatures shaped by, among other things, what they believe, where they live, how they shop, and who they sleep with. As a foreigner and a black man in England, Hall refused pious or reductionist interpretations of politics, such as dogmatic Marxism, which failed to account for people like him.

This is evident in his political essays, but it is conveyed more explicitly in a series of lectures he delivered at the University of Urbana-Champaign in the summer of 1983, recently reissued by Duke as Cultural Studies 1983, which would become the theoretical basis for the field. The lectures construct an analytic framework through borrowing from, and occasionally discarding, the ideas of Hoggart, Leavis, Durkheim, and Levi-Strauss, as well as Althusser and Gramsci. In these talks, we see Hall questioning Marxist orthodoxy, and grasping beyond it:

I wonder how it is that all the people I know are absolutely convinced they are not in false consciousness, but can tell at the drop of a hat that everybody else is. I have never understood how anybody can advance in the field of political organization and struggle by ascribing an absolute distinction between those who can see through transparent surfaces, through the complexity of social relations… Indeed, I have always undertaken to move from the opposite position, assuming that all ideologies which have ever organized men and women organically have something true about them.

Hall characterized ideology as the frameworks with which people translate and interpret society, and he saw them functioning all around him—on TV and in pubs, in classrooms and cinemas, and especially in media. As historian Frank Mort notes, while reading culture as political was groundbreaking at the time, it did draw on a history of left-leaning sociological work in Britain. (Accordingly, Hall once remarked that he wanted “to do sociology better than the sociologists.”) From the 1930s to the mid-60s, the Mass Observation movement aimed to chronicle the “everyday lives” of British people, and in the 1950s the Institute of Community Studies mapped the family structures of low-income communities in London. The Institute eventually spawned the Open University, where Hall taught for 18 years after leaving Birmingham.

By the mid-‘60s, Hall had married Catherine Barrett, a British feminist historian whose work would deeply influence his own, and had co-written The Popular Arts, one of the first books to apply serious analysis to popular film. At that point, the couple was living in the industrial English city, which, as James Vernon observes in an excellent essay on Hall and race, was riven by racial tensions. The year they moved there, Vernon writes, a “Conservative Party candidate ran an election campaign on the slogan ‘If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.’ ” Three years later, in 1968, conservative MP Enoch Powell would deliver his infamous “rivers of blood” speech in Birmingham, suggesting that a flood of immigrants would result in just that. That same year, Catherine gave birth to their daughter, the first of two children.

The late ‘60s and early ‘70s in England saw the rise of left-wing social movements, namely black power and feminism, which Catherine participated in by starting Birmingham’s first women’s liberation group. It was also the era of screaming headlines about crime and the so-called “Sus” laws, which gave police carte blanche to stop and harass “suspicious” young (black) men. This set the stage for Hall’s breakthrough work, which applied a zoom lens to the conflicted national mood. InPolicing the Crisis, Hall and his co-authors examined the explosion of news reports about the rise of “muggings” in the UK, arguing that this trend captured a moral panic about outsiders and immigrants, and generally reflected a feeling of decline as England, struggling with unemployment and an inefficient welfare state, transitioned away from a social democratic order.

Hall’s analysis, which elaborated on his earlier media studies work, was among the first to identify journalistic fearmongering and openness to austerity as the factors that would bring radical conservatives to power. In the final sentence, he predicted the continued ascent of Margaret Thatcher. Unfortunately, he was right. In 1979, the year after Crisis was published, Thatcher was elected Prime Minister.

Thatcher’s victory marked the beginning of a new historical moment. Elected by lower- and middle-class voters following England’s “winter of discontent,” Thatcher took aim at trade unions, entitlement programs, and nationalized industries—gutting the Keynesian public policy that had propped up the country for more than three decades. In its place, she offered what Hall later described as a “a deeply rooted, closed conservatism around a tiny myth of a nation with a homogenous culture… coupled with a rabid short-term individualism that is tied to the market place.”

In Thatcherism, Hall found the case study that would consume much of his work and, ironically, exemplify the kind of cultural politics he had hoped to activate on the left. His essay “The Great Moving Right Show,” written in 1979, was an attempt to dissect the phenomenon and its traction among voters. To Hall, Thatcherism reflected what Gramsci called an “organic” crisis: a moment when people cease to trust political leaders and parties, and upstart forces challenge those seeking to conserve the old order. During these periods, contradictions arise that band together disparate groups, and the very idea of what is considered “ordinary common sense” changes. Thatcher did not succeed by tricking voters, Hall posits, but rather by constructing a worldview that mapped onto their real lives and problems (if not their class identities) and advancing policies that reflected those concerns. He takes this as a reminder that “interests are not given but always have to be politically and ideologically constructed.” Hall would spend the rest of his life criticizing Thatcher, but he did credit the ingenuity of her tactics.

As the ‘80s advanced, the children of the Windrush generation took to the streets to protest the structural racism that their parents had endured in silence, and Hall turned his attention to the left’s failure in the face of Thatcherism. In his riveting 1987 essay “Gramsci and Us,” Hall blamed the Labour Party for its administrative understanding of politics, and its belief that political subjects are one-dimensional actors whose motivations can be reduced to economic interests. That year in Britain, there was no shortage of crises. Thatcher was reelected, race riots broke out in Leeds, and one person a day was dying of AIDS. Yet the left, Hall wrote,

does not seem to have the slightest conception of what putting together a new historical project entails. It does not understand the necessarily contradictory nature of human subjects, of social identities. It does not understand politics as a production. It does not see that it is possible to connect with the ordinary feelings and experiences which people have in their everyday lives, and yet to articulate them progressively to a more advanced, modern form of social consciousness. … It does not recognize that the identities which people carry in their heads—their subjectivities, their cultural life, their sexual life, their family life and their ethnic identities, are always incomplete and have become massively politicized.

Thatcher’s reality was now Britain’s, and party politics offered no answers. In light of this, Hall focused his attention on the “identities which people carry around in their heads.” Culture was now the main turf of politics, and individual identities were being negotiated on this turf. The left, despite its claims to inclusivity and social justice, had failed to provide a vocabulary that was human and specific enough for people to recognize themselves in.

Meanwhile, across England younger generations of black and Asian artists were discovering Hall’s work. This included Isaac Julien, Keith Piper, and other visual artists and filmmakers who would eventually form the British Black Arts Movement. John Akomfrah, a filmmaker whose archival documentary The Stuart Hall Project (2013) rivals Raoul Peck’s I am Not Your Negro in its intellectual and emotional depth, was among them. Describing Hall’s allure in Stuart Hall: Conversations, Projects, Legacies, Akomfrah wrote that “for a group of young people who had gone from coloured to black… and many other derogatory epithets in between in their very short lives,” Hall’s ability to move fluidly between identities, subjects and theoretical positions was precisely the appeal. In the last decades of his life, Hall became the founding chair of Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) and the photography organization Autograph ABP, both of which named their libraries in his honor, and he continued working with the British Film Institute, a relationship that extended back to the ‘60s.

Where organized politics had failed, art emerged as a way to access individual subjectivity. To see “how difference operates inside people’s heads,” Hall said in a 2007 interview, “you have to go to art, you have to go to culture—to where people imagine, where they fantasize, where they symbolize.”

Jessica Loudis is the editor of World Policy Journal.