COPENHAGEN (Reuters) - Greenland's main opposition party, which opposes a rare earth mining project, has become the biggest in parliament after securing more than a third of votes in a snap election.

The election result, closely watched by international mining companies wanting to exploit Greenland's vast untapped minerals resources, casts doubt on a mining complex at Kvanefjeld in the south of the Arctic island which holds one of the world's biggest deposits of rare earth metals.

With nearly all votes counted, the left-wing Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) party took 37% of votes, unseating the ruling social democratic Siumut party which secured 29% of votes, according to official results.

IA leader Mute Egede, 34, will be first to try to form a new government.

Though not opposed outright to mining, his party has a strong environmental focus. It has campaigned to halt the Kvanefjeld project, which aside from rare earths including neodymium - which is used in wind turbines, electric vehicles and combat aircraft - also contains uranium.

While most Greenlanders see mining as an important path towards independence, the Kvanefjeld mine has been a contention point for years, sowing deep divisions in the government and population over environmental concerns.

The island of 56,000 people, which former U.S. President Donald Trump offered to buy in 2019, is part of the Kingdom of Denmark but has broad autonomy.

The largely ice-covered island has the world's largest undeveloped deposits of rare-earth metals, according to geologists.

SKY NEWS

Wednesday 7 April 2021

A major mining project in Greenland aimed at exploiting the Arctic island's huge untapped mineral resources has been thrown into doubt following a snap election.

The main opposition Inuit Ataqatigiit (Community of the People) party, which is against the scheme at Kvanefjeld that holds one of the world's largest deposits of rare-earth metals, has become the biggest in parliament following the poll.

It took 37% of the votes, unseating the ruling social democratic Siumut party which secured 29%, official data showed.

Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) leader Mute Egede, 34, will be first to try to form a new government.

The election was triggered in the semi-autonomous Danish territory after the ruling coalition in the national assembly, the 31-seat Inatsisartut, collapsed due to a political split over the proposed mining project in southern Greenland.

Supporters saw the Kvanefjeld mine scheme as a potential source of jobs and economic prosperity.

The outgoing prime minister Kim Kielsen had pushed to give the green light to mine owner Greenland Minerals, an Australia-based company with Chinese ownership, to start operation.

One of the initial arguments for granting a mining license to Greenland Minerals was that the proceeds from the project would strengthen the island's economy and help the campaign to breakaway completely from Denmark through independence.

But Greenland resident Lise Svenningsen told Danish TV: "In the past, I was very preoccupied with the fact that, of course, we must be independent. And so will we one day.

"But I think that we should focus much more on the conditions of the population, and that politicians should try to act on things they promise year after year."

The largely ice-covered island has the world's largest undeveloped deposits of rare-earth metals, according to the US Geological Survey.

Estimates show the Kvanefjeld mine could hold the largest deposit of rare-earth metals outside China, which currently accounts for more than 90% of global production.

Rare-earth metals are used in a wide number of industries and products, including smartphones, wind turbines, microchips, batteries for electric cars and weapons systems.

In 2019, then US President resident Donald Trump floated an idea to buy Greenland from Denmark for strategic reasons.

The move sparked uproar in Copenhagen and was dismissed as absurd.

Climate change: An A-Z glossary

However, international interest in Greenland has continued as major powers - the US, China and Russia - race to establish their presence in the Arctic.

Washington opened a US consulate in Nuuk, Greenland's capital, last year as part of a new Arctic strategy adopted by the Trump administration.

Under a 1951 deal, NATO member Denmark has allowed the US to build bases and radar stations on Greenland.

Greenland, the world's largest island that is not a continent, has its own government and parliament, and relies on Denmark for defence, foreign and monetary policies.

April 7, 2021, 12:49 AM MDT

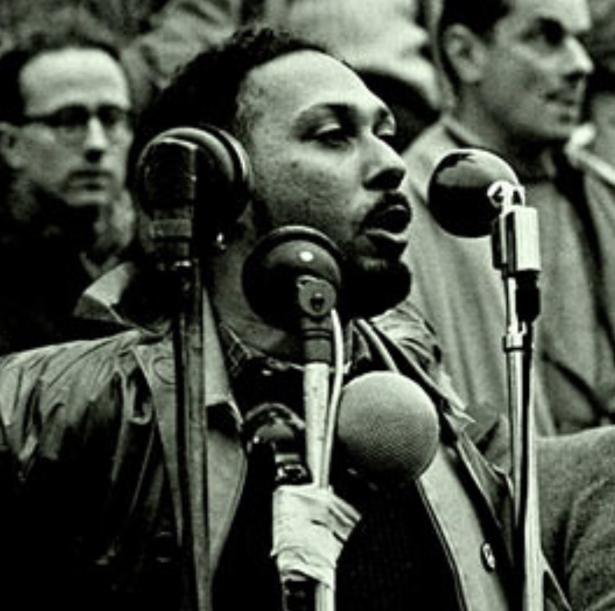

Members of the Inuit Ataqatigiit party celebrate following exit poll results in Nuuk, Greenland on April 6.

Photographer: Emil Helms/AFP/Getty Images

The people of Greenland have voted to oust a government that was planning to welcome foreign companies eager to tap the island’s rare-earth metals.

According to an early vote count of Tuesday’s parliamentary election, Greenland’s opposition Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) was set to become the biggest in the 31-seat chamber, garnering 37%, though the final result has yet to be announced. Siumut, the party of outgoing Prime Minister Kim Kielsen, was set to get about 29%, according to local broadcaster KNR.

Despite its tiny population of just 56,000, Greenland has grabbed international headlines in recent years, not least because of former U.S. President Donald Trump’s sudden interest in buying it back in 2019. Though he was rebuffed, the island’s geographic location and significant untapped natural resources have made it a continual target of international interest.

Javier Arnaut, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Greenland, said politics in the island nation tend to hover around the theme of attracting investments that might help it gain economic independence from Denmark. IA campaigned on a pledge to help break away from Denmark, which still oversees Greenland’s foreign, defense and monetary policies. But its program threatens to cut off investment.

IA, which now needs to build a coalition, has signaled it will shelve plans to allow a mining project at Kuannersuit near the southern tip of Greenland. It’s a decision that will hit Greenland Minerals, an Australian company in which Shenghe Resources Holding Ltd of China holds roughly a 10th.

The area is thought to have one of the world’s largest deposits of rare-earth minerals, which is increasingly regarded as a matter of national security because of its role in the production of high-tech products such as electric vehicles and semiconductors. Gaining access to such resources is one of the many arm wrestles between the U.S. and China.

About two-thirds of Greenlanders are against letting the mining project go ahead, mainly amid concerns about the environment, according to a poll published in the Sermitsiaq AG newspaper on Monday.

“The project is controversial,” Arnaut said. But ultimately, “Greenland is in a dilemma, choosing between protecting the environment and economic diversification and this time it looks like the environment is going to win.”.

“But mining for rare-earth minerals is going to be an ongoing topic,” he said

MORNING BRIEF

Greenland’s Rare-Earth Election

The outcome of today’s vote could decide whether the island bucks environmental concerns and embraces its potential as a rare-earth powerhouse.

Here is today’s Foreign Policy brief: Greenland votes in key legislative elections

Greenland’s Big Little Election

Voters in Greenland head to the polls today in legislative elections with uncharacteristically critical geopolitical implications.

At issue is a decision on whether to follow through on a rare-earth and uranium mine that would greatly boost the island’s economy. As Sam Dunning wrote in Foreign Policy in March, the mine already caused the government to fall in February, when a junior coalition partner quit after the majority Siumut party proposed halting public consultations for the mine’s extraction permit.

With the world’s largest undeveloped deposits of rare-earth minerals, Greenland has the potential to become a world leader in producing the materials essential to high-demand products like smartphones and military hardware like the F-35 fighter jet.

Geopolitical hotspot. Greenland is of interest to the United States and its allies as they have watched China race ahead as a rare-earth leader. Beijing now accounts for two-thirds of rare-earth mining and 90 percent of global production. Such is China’s dominance, the Quad nations of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States have begun talks on a rare-earth supply chain partnership.

The companies behind the proposed mine reflect international interest in the metals. An Australian company, Greenland Minerals, has been preparing the site for the past 15 years, while a Chinese firm, Shenghe Resources—itself part-owned by the Chinese government—is Greenland Minerals’ main investor.

Mining the Future, a special report by FP Analytics, is the first systematic and comprehensive assessment of China’s accumulation of control and influence over a range of critical metals and minerals and the supply chains on which the future of the high-tech industry depends. Read it now.

The mine has nationalistic appeal for the island, where independence from Denmark has been a long-sought goal. Although Greenland is largely autonomous, Denmark still currently pays half of the island’s budget, so any opportunity to build economic independence remains an attractive proposition.

Environmental concerns over radioactivity and pollution seem to be winning out among the country’s voters; however, polls currently favor the opposition Inuit Ataqatigiit, a democratic socialist party opposed to the mine.

What pandemic? Voters will cast ballots today in an atmosphere largely free of the coronavirus fears that have plagued the rest of the world. To date, Greenland has had no COVID-19 deaths nor related hospitalizations. Its total case count is 31, which, even considering its tiny population of 56,000, ranks it among the best performers in the world in taming the virus.

Wintry woes. Even so, all is not rosy in Greenland. Incidents of violence have skyrocketed over the past few years, jumping 46 percent from 2018 to 2020. Suicide rates in Greenland are the highest in the world. And rapid migration from periphery towns to the capital, Nuuk, has also triggered an increase in homelessness, as new housing fails to keep up with demand.

All of these problems require long-term, intergenerational solutions, Steven Arnfjord, the head of the social sciences department at the University of Greenland, told Foreign Policy, which is something that a mine and its associations with independence can’t remedy. “If you’re going to be dependent on mining rare-earths, that’s a 25 to 30 year spectrum. Then it’s drained out,” Arnfjord said. “Of course, mining can be a good deal, but I’ve yet to see a multinational mining company really doing it for the benefit of the country that they’re in.”

Polls close in Greenland election closely watched by global mining industry

Reuters

COPENHAGEN (Reuters) -Voting stations closed in Greenland on Tuesday evening in a snap election that could unseat the ruling party and help decide the fate of vast deposits of rare earth metals that international companies want to exploit.

The Arctic island of 56,000 people, which former U.S. President Donald Trump offered to buy in 2019 only to be told it was not for sale, is part of the Kingdom of Denmark but has broad autonomy.

International companies are watching the election closely as they compete for the right to develop Greenland's untapped deposits of rare earth metals including neodymium, which is used in wind turbines, electric vehicles and combat aircraft.

Global warming and melting ice have made Greenland more attractive for investment as access by sea has become easier. Trump's offer for Greenland was intended to help address Chinese dominance of rare earth supplies.

But concern in Greenland is mounting about the potential environmental impact of plans to build a large mining complex at Kvanefjeld in the south of the island, a site that contains uranium as well as neodymium.

A junior party withdrew from the coalition government in February as opposition to the project grew, prompting the decision to call Tuesday's election to the 31-seat parliament.

MINING POTENTIAL

Opinion polls before the election showed the social democratic Siumut Party, which has led all governments since 1979 except for one period from 2009-2013, trailing the main opposition party, Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA).

Support from Siumut helped secure preliminary approval for the Kvanefjeld project, which is licensed to Australia's Greenland Minerals Ltd , in which China's Shenghe Resources Holding Co Ltd is the biggest shareholder.

If IA can form a coalition to govern, it could raise questions about the project. IA has a zero-tolerance policy for uranium and has criticised the project.

Polling stations closed at 8 p.m. (2200 GMT) and deputies will be elected for four years. Authorities hope to announce final results before 1 a.m. Wednesday (0300 GMT), local media reported.

No preliminary results had so far been made public.

Apart from mining, campaign issues have included housing, the fishing industry and efforts to gain more autonomy.

Greenland's mining potential is widely seen as vital to its prospects of achieving more economic independence, as its $3 billion economy and large public sector are heavily reliant on grants from Denmark.

A majority of Greenlanders view independence from Denmark as a long-term goal but say economic development is needed first.

(Reporting by Nikolaj Skydsgaard; Editing by Gareth Jones and Peter Cooney)

BACKGROUNDERS

Mining — and independence — at the heart of Greenland's election

Dispute over controversial rare earths mine collapsed former government

Greenlanders will head to the polls Tuesday in an election partly defined by bitter disputes over the future of resource development in the Arctic nation.

The April 6 election was called after a controversial mining project in southern Greenland sparked an internal spat within the ruling coalition.

The project, in an area known as Kannersuit near the community of Narsaq, would see an Australian-listed mining company, backed partly by Chinese investors, mine for rare earth metals and uranium in a pristine region used by fishermen, shepherds and tourist guides.

But the governing party's push for the mine has also been closely tied to the country's push for independence from Denmark, as it seeks to gradually reduce its dependence on a roughly $700 million annual transfer from the former colonial power.

"This is a project that probably really would make a difference, in terms of providing jobs and a healthy dose of income to the national purse," said Ulrik Pram Gad, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies.

"But it's also a very controversial project, in the sense that … it's really [about], should we sacrifice this beautiful spot and the kind of life that people live there, for the sake of the greater good — in this case, inching towards national independence?"

Protests and death threats

Just five kilometres from Narsaq is a mountain home to one of the world's largest unexploited deposits of rare earth metals, an important strategic resource currently mined almost exclusively in China.

The proposed mine would see neodymium, used for wind turbines and combat aircraft, mined alongside uranium, the mining of which was banned on the island until 2013.

The project was backed by the ruling Siumut party, which has governed Greenland for all but one term since 1979. But as the government began public hearings on the project, support within the governing coalition eroded in the face of outrage from local residents.

Hearings in Narsaq were greeted by grassroots environmental protests and even death threats aimed at cabinet ministers who supported the project. Hundreds of NGOs signed an open letter asking that the area be deemed an Arctic sanctuary instead.

Many fear the mine will negatively impact not only fishing, the core of Narsaq's economy, but tourism and the region's budding agriculture industry as well.

But others see the project, and others like it, as key steps toward Greenland's financial independence.

A boost to the treasury

Currently, Denmark pays for two-thirds of the Greenland government's budget, according to Maria Ackrén, a professor of political science at Ilisimatusarfik (University of Greenland).

But royalties from the mine could cover as much as 15 per cent of public expenditures, Reuters reports — roughly $250 million per year.

"It is clear that the economy should be diversified," she said. "Those parties that are in favour see this as … a step toward independence."

That puts Inuit Ataqatigiit, Siumut's left-wing opposition, on tricky footing. As outspoken critics of the Kannersuit project, they stand to see their vote increase in southern Greenland, where Pram Gad says Siumut normally performs strongly.

But they are also a party that strongly supports independence. Objecting to resource projects puts them further from that goal, and makes it harder to form coalitions in government, Ackrén said.

That may explain the party's so-far muted opposition to a neighbouring rare earths project, called Tanbreez, that some believe poses fewer risks to the environment.

"I think there are lots of compromises to be made," said Ackrén.

Unclear who will lead

Siumut, the original proponents of the project, could also stand to gain from opposition to the project. That's because the party's internal fight over the mine is still unresolved.

Erik Jensen ousted Kim Kielsen as party leader last year over his government's support for the mine. But in a rejection of convention, Kielsen remained on as premier.

That means, no matter who wins, it's not clear who will lead the government.

"It's unclear how this will play out in the election," said Martin Breum, a Danish journalist covering the election.

The candidate with the most votes typically wins the right to form a government. But if Kielsen were to outperform Jensen on April 6, it's hard to say who would be in charge.

"He might say, 'I would like to run the government,' and then it would be hard for … the new chairman of the party to refuse him that privilege," Breum said.

"It is very, very hard to predict."

All politics is local

All this means significant uncertainty for the mineral resources companies hungrily eyeing the island nation.

Reuters has quoted the acting minister of resources, Vittus Qujaukitsoq, saying that in deciding on the Kannersuit project, the "credibility of the whole country is at stake."

But voters are unlikely to be moved by the anxiety of international investors.

"Development, when seen bottom up, is primarily about services," said Pram Gad. "There are these places [in Greenland] where very basic services don't really exist."

Pram Gad and other experts say, for most of Greenland, commitments to housing, social services and spreading the wealth generated by fisheries are more likely to sway votes than a party's position on the Kannersuit mine.

All to say, while the fate of Kannersuit may be attracting election-watchers from around the world, as always in politics, all issues are local.

With files from Reuters

Why Greenland's election matters

Greenland heads to the polls on Tuesday in snap elections which could have major consequences for international interests in the Arctic.

The vast territory, which belongs to Denmark but is autonomous, lies between North America and Europe and has a population of just 56,000.

Greenland's economy relies on fishing and and Danish subsidies, but melting ice and a planned mine could change the course of the vote - and the territory's future.

Here's what you need to know

What's at stake

Disagreement over a controversial mining project in the south of Greenland has split the government and paved the way for this week's election.

The company that owns the site at Kvanefjeld says the mine has "the potential to become the most significant western world producer of rare earths", a group of 17 elements used to manufacture electronics and weapons.

The rush to claim an undersea mountain range

The Simuit (Forward) Party supports the development, arguing that it would provide hundreds of jobs and generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually over several decades, which could lead to greater independence from Denmark.

But the opposition Inuit Ataqatigiit (Community of the People) party has rejected the proposal, amid concerns about the potential for radioactive pollution and toxic waste.

The future of the Kvanefjeld mine is significant for a number of countries - the site is owned by an Australian company, Greenland Minerals, which is in turn backed by a Chinese company.

Why is Greenland important?

Greenland has hit the headlines several times in recent years, with then-President Donald Trump suggesting in 2019 that the US could buy the territory.

Denmark quickly dismissed the idea as "absurd", but international interest in the territory's future has continued.

China already has mining deals with Greenland, while the US - which has a key Cold War-era air base at Thule - has offered millions in aid.

US announces millions in aid for Greenland

Could Greenland become China's Arctic base?

Denmark has itself acknowledged the territory's importance: in 2019 it placed Greenland at the top of its national security agenda for the first time.

And in March this year, one think tank concluded that the UK, the US, Australia, Canada and New Zealand - known collectively as the Five Eyes - should focus on Greenland to reduce their dependency on China for key mineral supplies.

Mining isn't Greenland's only issue, however.

The territory is on the front line of global warming, with scientists reporting record ice loss last year. This in turn has significant implications for low-lying coastal areas around the world.

But it is the retreating ice that has both increased mining opportunities and allowed ships to navigate waters more easily through the Arctic, which could reduce global shipping times.

Greenland is therefore an attractive prospect for western countries seeking to counter Russia's military build-up in the Arctic.

HELSINKI — Greenland is holding an early parliamentary election Tuesday focused in part on whether the semi-autonomous Danish territory should allow international companies to mine the sparsely populated Arctic island's substantial deposits of rare-earth metals.

Lawmakers agreed on a snap election after the centre-right Democrats pulled out of Greenland's three-party governing coalition in February, leaving the government led by the centre-left Forward party with a minority in the national assembly, the 31-seat Inatsisartut.

One of the main reasons the Democrats withdrew was a deep political divide over a proposed mining project involving uranium and rare-earth metals in southern Greenland. Supporters see the Kvanefjeld mine project as a potential source of jobs and prosperity.

Outgoing Prime Minister Kim Kielsen pushed to give the green light to mine owner Greenland Minerals, an Australia-based company with Chinese ownership, to start operation. Erik Jensen — Kielsen’s recent successor as Forward party leader — is more hesitant and has been opposed to granting outright a mining license to the company.

Recent election polls showed the left-leaning Community of the People party (Inuit Ataqatigiit), a staunch opponent of the mine project, in position to become the largest party in the Greenlandic Parliament.

The opposition party has claimed that a majority of Greenland’s 56,000 inhabitants, most of them indigenous Inuit people, are against the project, largely for environmental reasons.

Observers stress political surveys in Greenland have proved to be uncertain, and the over 30% support level enjoyed by the Community of the People party in pre-election polls may not necessarily hold.

“A third of the voters decide at the last minute, and the support for (Community of the People) is overestimated,” said political scientist Leander Nielsen at the University of Greenland, as quoted by the Norwegian news agency NTB.

One of the Forward's party's initial justifications for granting a mining license to Greenland Minerals was that the proceeds from the project would strengthen Greenland’s economy and thus help in efforts to disengage the island completely from Denmark through independence — an ambition nurtured by Forward, the Community of the People and some other parties.

“In the past, I was very preoccupied with the fact that, of course, we must be independent. And so will we one day,” Greenland resident Lise Svenningsen told the Danish public broadcaster DR. “But I think that we should focus much more on the conditions of the population, and that politicians should try to act on things they promise year after year.”

The mining proposal is relevant beyond Greenland. The largely ice-covered island has the world’s largest undeveloped deposits of rare-earth metals, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Estimates show the Kvanefjeld mine could hold the largest deposit of rare-earth metals outside China, which currently accounts for more than 90% of global production.

Rare-earth metals are used in a wide array of sectors and products, including smartphones, wind turbines, microchips, batteries for electric cars and weapons systems.

In 2019, former President Donald Trump floated an idea to buy Greenland for the United States from Denmark for strategic reasons. The initiative was met with uproar in Copenhagen and dismissed as an absurd idea. However, international interest in Greenland has continued as major powers — the U.S., China and Russia — are racing to establish their presence in the Arctic.

Washington opened a U.S. consulate in Nuuk, Greenland's capital, last year as part of a new Arctic strategy adopted by the Trump administration.

Under a 1951 deal, NATO member Denmark has allowed the U.S. to build bases and radar stations on Greenland. The U.S. Air Force currently maintains one base in northern Greenland, Thule Air Force Base, 1,200 kilometres (745 miles) south of the North Pole.

Greenland, the world’s largest island that is not a continent, has its own government and Parliament, and relies on Denmark for defence, foreign and monetary policies.

Voting in Tuesday's election is set to end at 2200 GMT. Initial results are expected on Wednesday.

Jari Tanner, The Associated Press