The creation of a human–long-tailed macaque hybrid embryo roiled the internet. We asked experts what this means

By MATTHEW ROZSA

APRIL 16, 2021

Depending on your point of view, the creation of an embryo that is part-human and part-monkey is either a great opportunity for medical experts to create organs and tissues for human transplantation; or, the starting point of a horror movie.

Either way, that premise is now a reality.

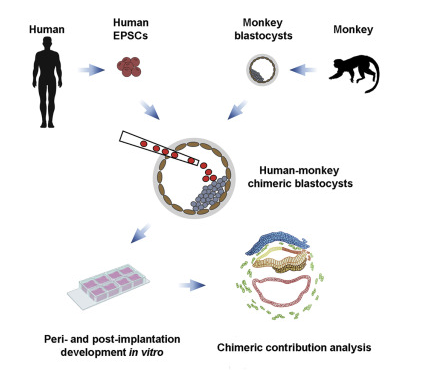

Per a new study published in the scientific journal "Cell," a team of scientists led by Dr. Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of California's Salk Institute for Biological Studies created the first embryo to contain both human cells and those of a non-human primate — in this case, those of long-tailed macaques. This type of creation is known as a "chimera," or an organism that contains genetic material from two or more individuals.

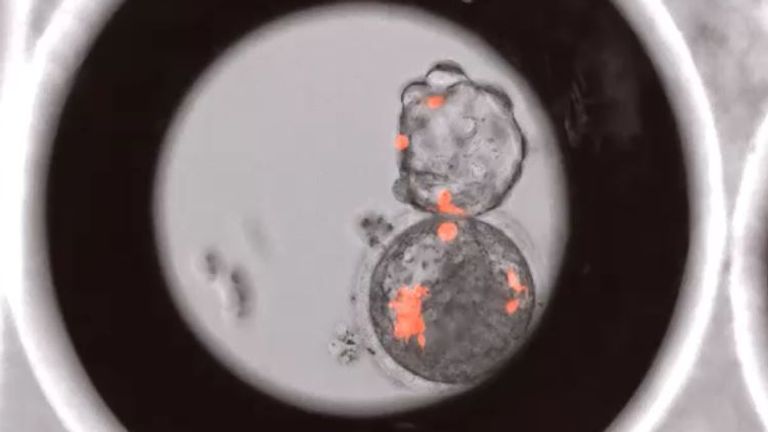

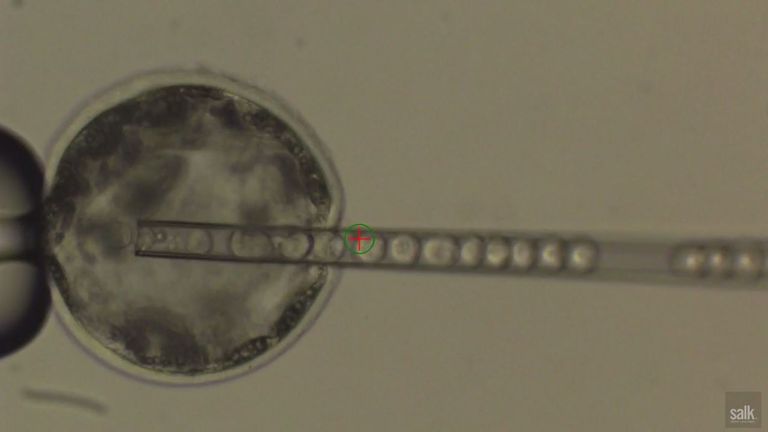

Izpisua Belmonte's team injected 25 human cells known as induced pluripotent stem cells (or iPS cells generally, and hiPS cells when they come from humans) into the embryos of long-tailed macaque monkeys. Human cells were able to grow inside 132 of the embryos and the scientists were able to study the results for up to 19 days. Many sources report this as the first half-human half monkey embryo, although The Guardian claims that the same team actually developed one in 2019. Salon reached out to Izpisua Belmonte to clarify and will update the story if or when he responds.

This chimera experiment wasn't the product of mad scientists testing ethical limits: it had real scientific purpose and value. Indeed, with more research and a bit of luck, scientists could use the knowledge from these experiments to grow human organs in other animals.

"This knowledge will allow us to go back now and try to re-engineer these pathways that are successful for allowing appropriate development of human cells in these other animals," Izpisua Belmonte told NPR.

The embryo in question is not the first chimera to be created by scientists: For instance, Izpisua Belmonte and the Salk Institute were marginally effective in creating human-pig chimeras in 2017, the same year that researchers in Portugal created a chimera virus (in their case, a mouse virus with a human viral gene). There are also chimeras that occur naturally, such as twins who absorb some of their sibling's DNA. American singer Taylor Muhl says that a large section of skin on her torso is darker because it comes from her fraternal twin's genetic material.

The potential advantage of creating human-monkey chimeras is significant. It is often difficult for doctors to have enough organs to provide transplants to patients who desperately need them, and creating successful chimeras could allow scientists to manufacture organs rather than depending on donors. As Izpisua Belmonte told NPR, "This is one of the major problems in medicine — organ transplantation. The demand for that is much higher than the supply."

Julian Koplin, a research fellow with the Biomedical Ethics Research Group, Murdoch Children's Research Institute and Melbourne Law School at the University of Melbourne, pointed out in an email to Salon that the bigger concern about chimeras is when they lead to live-born creatures. These were just in the early embryonic stage, but if scientists are eventually able to develop human-pig chimeric animals for organ transplants, things could become ethically questionable.

"Most people think that humans have much greater moral status than (say) a pig," Koplin explained. "However, a human-pig chimera would straddle these categories; it is neither fully a pig nor fully human. How, then, should we treat this creature?"

Indeed, the chimeric embryo experiment already entered some ethical gray areas. As Koplin noted, "in many jurisdictions, human embryo research is subject to the '14-day rule' (which limits research to the first 14 days of embryo development.) These chimeric embryos were cultured until some reached 19 days post-fertilization. Should the study have stopped at 14 days? Arguably not, since only a small proportion of their cells were human. But how many human cells are too many? At what stage should a chimeric embryo be treated like a human embryo?"

Dr. Daniel Garry, a professor at the University of Minnesota who has written extensively about the science and ethics of chimeras, broke down the issues with Salon by email. He noted that ethical concerns against the technology include fears of human cells contributing to "off-target" organs such as the brain, although he added that he and his colleagues "recently showed that this contribution does not occur." Likewise, he feared the possibility that a human embryo could wind up being inadvertently developed in a large animal.

Moreover, Garry said that with chimera research in general, ethics issues abound regarding the humans who contribute cells to such research. In the case of the monkey-human chimera embryo experiment, humans who contributed cells that were reprogrammed were aware and gave consent to have that happen.

Advertisement:

Garry added that there are also questions about "whether some organs might be appropriate but others not — for example, generating a pancreas or heart is OK, but having a monkey or a pig with human skin or human hair may not be OK for some." He also noted that there are usually ethical arguments that arise whenever there is a "paradigm shifting discovery" from people who are that "leery of scientific advances."

At the same time, Garry said that there are a number of strong ethical arguments in favor of chimeras. He pointed to how there are many terminal chronic diseases which do not have curative therapies and whose patients would benefit from the biotechnology created by chimera research. It could reduce healthcare costs, increase the supply of transplant organs and potentially reduce or eliminate the need for drugs to prevent an adverse immune system response.

Koplin said such chimera studies could advance medical science.

"As I understand it, the aim of this study was to help improve techniques for creating human-animal chimeras," Koplin explained. "Chimeric animals could be used for disease modelling or to generate transplantable human organs. These advances could save lives — which is an important moral reason to pursue them."

Henry T. Greely, a professor for the Center for Law and the Biosciences at Stanford University who wrote about the ethical questions pertaining to chimeras in "Cell," told Salon that defining what counts as a chimera is "tricky."

"Every time a person gets an organ transplant, the result is an intra-species chimera: an organism made up of cells from two members of the same species," Greely noted. "Another example is the way that some pregnant women end up permanently carrying cells from their fetus. When a human gets a pig heart valve, she becomes an inter-species chimera. When a mouse gets human cells, for example to test to see how committed they are to a development path (whether or not they are "pluripotent"), that's a chimera." He also noted that scientists might put human brain tissue into a rat's brain to study the human cells in a way that would not be ethical to do in other people, since they eventually need to kill the test subject and study its brain slices.

Researchers say the work could help tackle transplant shortages, but experts warn such hybrid organisms pose major challenges.

Friday 16 April 2021

Human cells have been grown in monkey embryos by scientists in the US, sparking ethical concerns and warnings that it "opens a Pandora's box".

Those behind the research say their work could help tackle the severe shortage of transplant organs as well as enable better overall understanding of human health, from the development of disease to ageing.

But some experts in the UK have highlighted the significant ethical and legal challenges posed by the creation of such hybrid organisms and called for a public debate.

Concerns have been raised after researchers from the Salk Institute in California produced what is known as monkey-human chimeras.

This involved human stem cells - special cells that have the ability to develop into many different cell types - being inserted in macaque embryos in petri dishes in the lab.

The aim is to understand more about how cells develop and communicate with each other.

Chimeras are organisms whose cells come from two or more individuals.

In humans, chimerism can naturally occur following organ transplants, where cells from the organ start growing in other parts of the body.

Professor Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, who is leading the research, said: "These chimeric approaches could be really very useful for advancing biomedical research not just at the very earliest stage of life, but also the latest stage of life."

In 2017, he and his team created the first human-pig hybrid, where they introduced human cells into early-stage pig tissue but found the environment provided poor molecular communication.

As a result, the researchers decided to investigate lab-grown chimeras using a more closely related species.

The human-monkey chimeric embryos were monitored in the lab for 19 days before being destroyed.

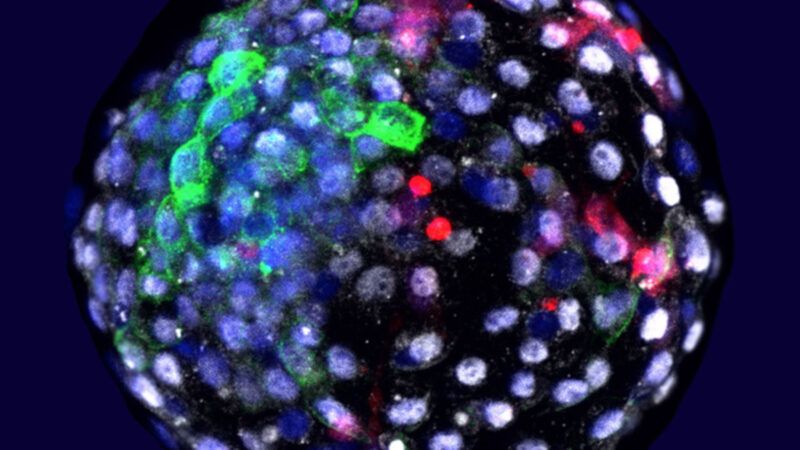

According to the scientists, the results, published in the journal Cell, showed human stem cells "survived and integrated with better relative efficiency than in the previous experiments in pig tissue".

The team said understanding more about how cells of different species communicate with each other could provide an "unprecedented glimpse into the earliest stages of human development" as well as offer scientists a "powerful tool" for research on regenerative medicine.

Insisting that their research has met current ethical and legal guidelines, Prof Izpisua Belmonte said: "As important for health and research as we think these results are, the way we conducted this work, with utmost attention to ethical considerations and by coordinating closely with regulatory agencies, is equally important.

"Ultimately, we conduct these studies to understand and improve human health."

Responding to the research, Dr Anna Smajdor, lecturer and researcher in biomedical ethics at the University of East Anglia's Norwich Medical School, said: "This breakthrough reinforces an increasingly inescapable fact: biological categories are not fixed - they are fluid.

"This poses significant ethical and legal challenges."

She added: "The scientists behind this research state that these chimeric embryos offer new opportunities, because 'we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans'.

"But whether these embryos are human or not is open to question."

Prof Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, University of Oxford, said: "This research opens Pandora's box to human-nonhuman chimeras.

"These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans. That is one of the long-term goals of this research.

"The key ethical question is: what is the moral status of these novel creatures? Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed."

Some bioethicists have expressed concerns about the research.

"My first question is: Why?" asked Kirstin Matthews, a fellow for science and technology at Rice University's Baker Institute, when interviewed by NPR. "I think the public is going to be concerned, and I am as well, that we're just kind of pushing forward with science without having a proper conversation about what we should or should not do."

One often-mentioned worry is that human neurons could possibly get installed into an animal's brain and somehow make its consciousness more humanlike. Another fear is that human cells that produce sperm and eggs could migrate into the testes and ovaries of monkeys, who might then mate and create a human fetus. Surely such possibilities require further ethical reflection, but the mixed cells in these experiments got nowhere near such possibilities.

As the researchers conclude, "this line of fundamental research will help improve human chimerism in species more evolutionarily distant that for various reasons, including social, economic, and ethical, might be more appropriate for regenerative medicine translational therapies." Translation: This research aims to help scientists figure out how to grow fully human organs in other animals, such as pigs and sheep, that are not as evolutionarily close to us as monkeys. Given the ongoing and persistent transplant organ shortage, let's hope this work succeeds.

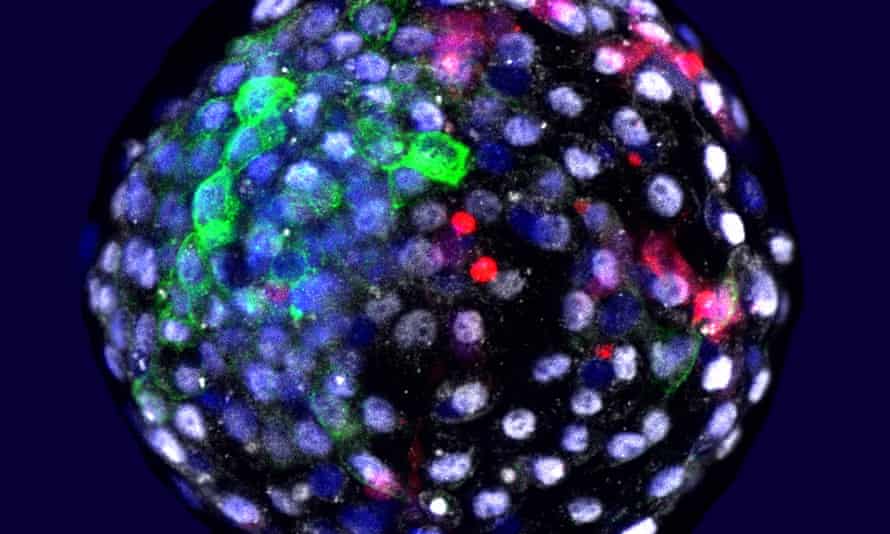

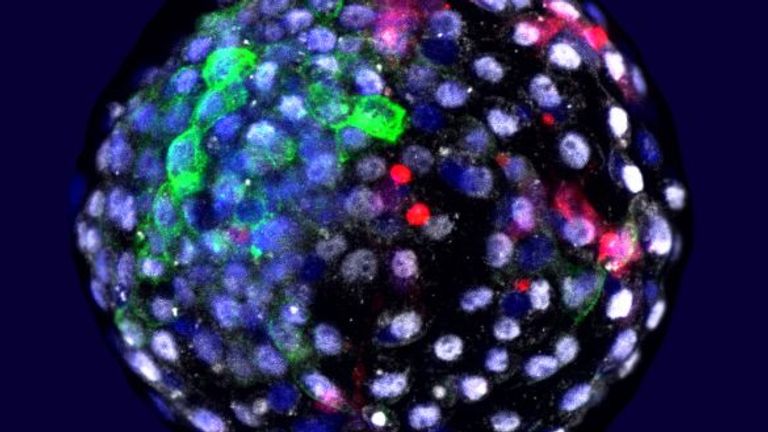

A human-monkey blastocyst, an early stage of embryo development

Weizhi Ji, Kunming University of Science and Technology

Researchers have grown human cells in monkey embryos with the aim of understanding more about how cells develop and communicate with each other.

Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte at the Salk Institute in California and his colleagues have produced what are known as human-monkey chimeras, with human stem cells – special cells that have the ability to develop into many different cell types – inserted in macaque embryos in petri dishes in the lab.

However, some ethicists have raised concerns, saying this type of work “poses significant ethical and legal challenges”.

Chimeras are organisms whose cells come from two or more individuals. In humans, chimerism can naturally occur following organ transplants, where cells from that organ start growing in other parts of the body.

Izpisua Belmonte says the team’s work could pave the way in addressing the severe shortage in transplantable organs, as well as help us understand more about early human development, disease progression and ageing. “These chimeric approaches could be really very useful for advancing biomedical research not just at the very earliest stage of life, but also the latest stage of life,” he said.

In 2017, Izpisua Belmonte and his colleagues created the first human-pig chimera, where they incorporated human cells into early-stage pig tissue but found that human cells in this environment had poor molecular communication. So the team decided to investigate lab-grown chimeras using a more closely related species: macaques.

Read more: Exclusive: Two pigs engineered to have monkey cells born in China

The human-monkey chimeric embryos were monitored in the lab for 19 days before being destroyed. The team says the human stem cells “survived and integrated with better relative efficiency than in the previous experiments in pig tissue”.

Izpisua Belmonte says the work meets current ethical and legal guidelines. “As important for health and research as we think these results are, the way we conducted this work, with utmost attention to ethical considerations and by coordinating closely with regulatory agencies, is equally important.”

“This breakthrough reinforces an increasingly inescapable fact: biological categories are not fixed – they are fluid,” said Anna Smajdor at the University of East Anglia, UK, in a statement. “This poses significant ethical and legal challenges.”

“The scientists behind this research state that these chimeric embryos offer new opportunities, because ‘we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans’. But whether these embryos are human or not is open to question,” she said.

Julian Savulescu at the University of Oxford said in a statement: “This research opens Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras. These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans. That is one of the long-term goals of this research.”

“The key ethical question is: what is the moral status of these novel creatures?” he said. “Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed.”

Journal reference: Cell, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.020

Read more: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2274762-human-cells-grown-in-monkey-embryos-raise-ethical-concerns/#ixzz6sL74E5gQ

Cell

Cell Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe

Image source: Javier Duran/Adobe