(Monty Rakusen/Getty Images)

CARLY CASSELLA

27 APRIL 2021

Humans around the world are consuming far more natural resources than our planet can continue to sustain, condemning the majority of people to ecological poverty, according to new research.

When researchers tried to put a number on our natural resource deficit for the year 2017, they found our global population of over 7.5 billion people had spent 173 percent of the world's total biocapacity that year.

This is obviously a major overshoot, and it's part of a trend that has gotten much worse in recent decades. In 1980, humanity was using only 119 percent of the world's biocapacity.

Much of the surge in demand since then has been driven by wealthier nations, requiring higher and higher standards of living, even if they have to buy resources from elsewhere.

Today, nearly three quarters of all people live in nations with lower-than-average incomes and a scarcity of natural resources, which means they simply can't compete.

Clearly, the path we are on today cannot be trod forever. If the world is truly serious about eradicating poverty, then experts say we cannot keep ignoring the limiting factor that is Earth's resources.

Dividing the world's countries into four categories, based on their gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and their local ecological deficit, researchers have illustrated an unsustainable shift in humanity's demand for resources.

If we don't seek to rapidly improve resource security - through conservation and restoration, fossil fuels cuts, sustainable development, and shifting consumption patterns - the authors argue our natural capital will be unable to recover, and our hope for a more equal future will be wholly undermined.

In the year 1980, 57 percent of the global population lived in a country with the "double curse" of a below-average income and a deficit in biological resources, the researchers found. In 2017, that number had jumped to 72 percent.

On the other hand, higher income countries with resource deficits make up only 14 percent of the world population, but this minority demands an astonishing 52 percent of the planet's biocapacity.

Switzerland and Singapore are two notable nations that fall into this latter category, which means they are shielded from resource insecurity because they have the money to buy what they need from other places.

To live in a truly sustainable way, scientists think we should be using no more than half our planet's resource capacity, but if everyone in the world lived like those in higher income, low resource countries, like Switzerland, we would need roughly 3.67 planet Earths to meet global demand.

"If the development patterns of these cities or territories are not replicable, there is only one way for such entities to avoid their own demise: they must be certain that they can financially outcompete everybody else on this planet forever to secure their resource metabolism," the authors conclude.

"Requiring such a strategy to succeed is precarious for regions at any income level."

But it's especially dangerous for lower income regions, who cannot compete for resources at the same level. Without assistance from wealthier nations, there's really not a lot these nations can do.

In fact, researchers argue lower income countries currently face a catch-22. Continuing with the status quo will no doubt make their current resource crisis worse, but making rapid changes to human resource consumption will also cost a lot of money, which many simply cannot afford.

What's more, because wealthier nations consume many more resources than are absolutely necessary to live, they have much more wiggle room in the face of future disaster.

In an economic downturn, for instance, a loss of resources isn't as catastrophic for Spain as it would be for Niger or Kenya, where such a rapid loss could erode food and energy security for many more people, putting their very lives at risk.

"This paper strengthens the case that biological resource security is a far more influential factor contributing to lasting development success than most economic development theories and practices would suggest," the authors conclude, "and shows how unevenly it affects distinct human populations."

Clearly, we are spending more than humanity or our planet can afford.

The study was published in Nature Sustainability.

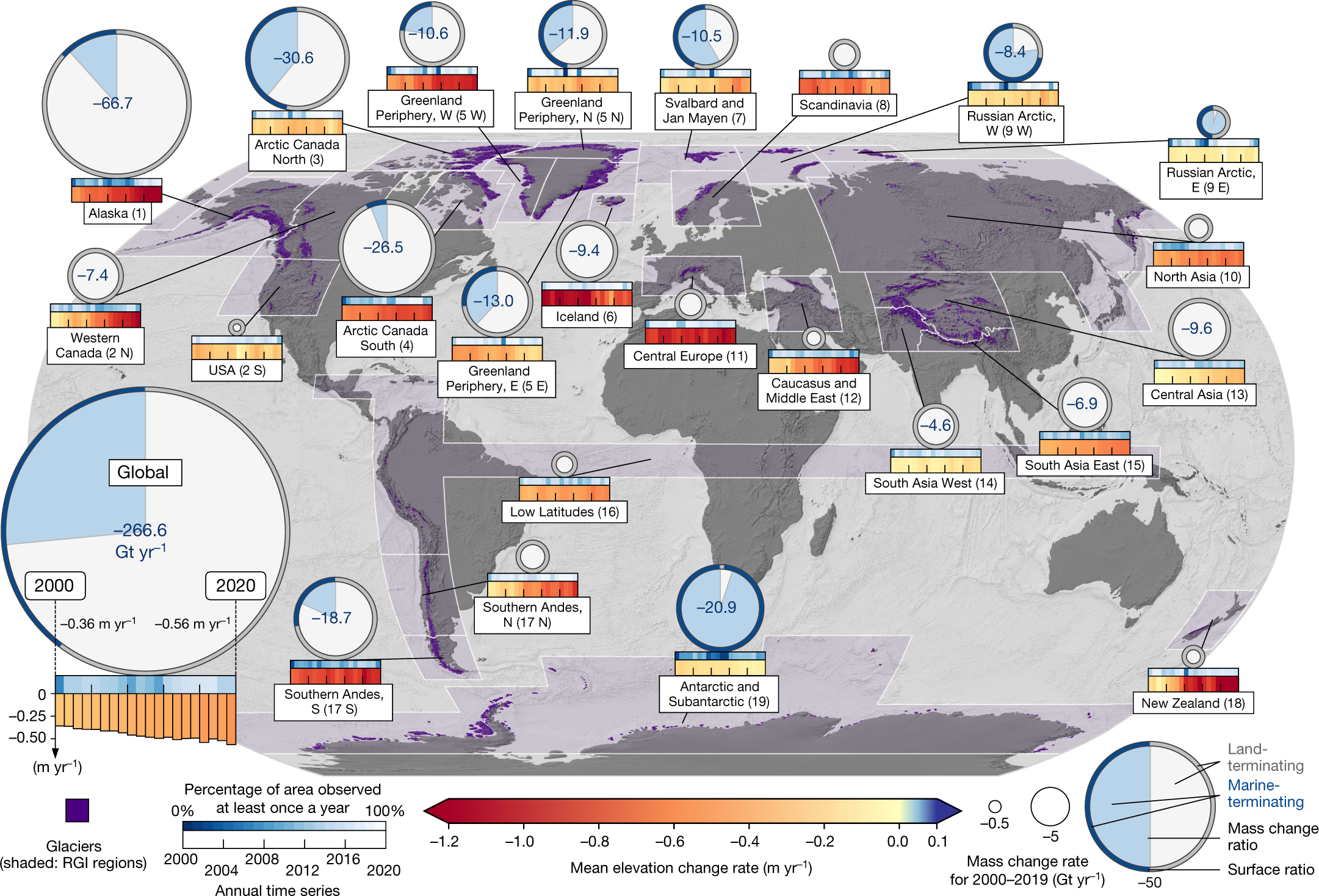

Regional and global mass change rates with time series of mean surface elevation change rates for glaciers. (

Regional and global mass change rates with time series of mean surface elevation change rates for glaciers. (