The Fight to Define What ‘Clean’ Energy Means

Dharna Noor

GIZMONDO

12/5/2021

Photo: Sean Gallup (Getty Images)

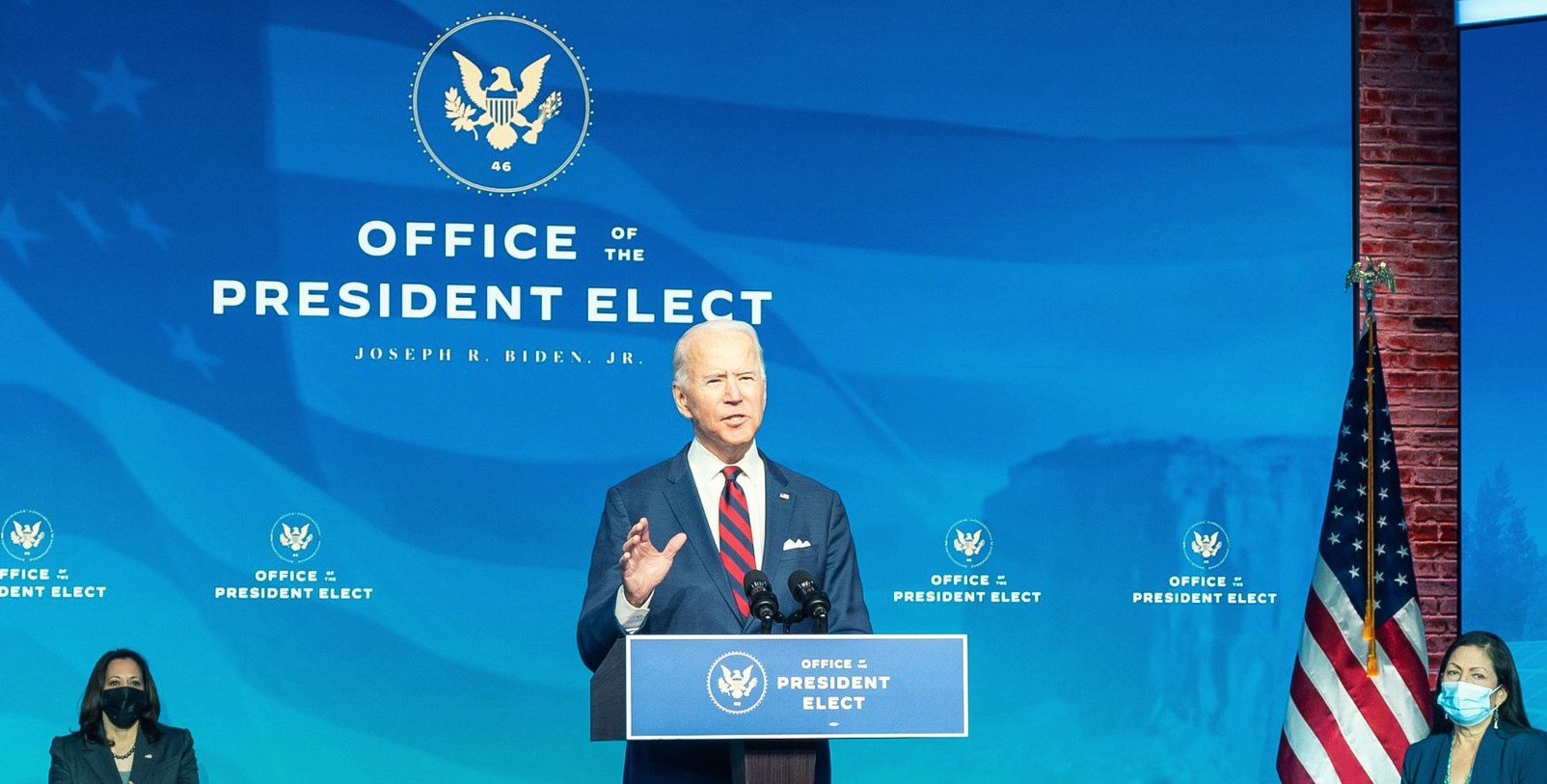

After four years of backsliding under former President Donald Trump, the U.S. is back to increasing its climate ambitions. But there’s a fight brewing over what exactly constitutes zero-carbon energy, showing that challenges decarbonization faces.

President Joe Biden has proposed a clean electricity standard to reduce emissions, and various proposals and bills would create one for the U.S. On Wednesday, though, 650 organizations including Climate Justice Alliance, Greenpeace, Food and Water Watch, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Friends of the Earth sent an open letter to Congress asking it to eschew the clean electricity standard proposals and take another route to clean energy, known as a renewable electricity standard, instead.

If you’re confused, I don’t blame you—the terms “clean” and “renewable” for energy are often used interchangeably. But in this case, while the CES defines non-polluting energy as anything that falls under a certain pollution standard, the RES simply lists out forms of energy that count. The letter calls for a bill that would require the U.S. to solely use renewable sources—defined as wind, solar, and geothermal—to meet its carbon-free electricity needs by 2030. That’s five years ahead of Biden’s current timeline in addition to the only renewables requirement.

“One of the most basic and important questions of climate policy is how you define clean energy,” said Lukas Ross, program manager at Friends of the Earth while noting that “definitions matter.”

Capitol Hill has seen a number of CES proposals. One that the letter specifically cites, the CLEAN Future Act of 2021, sets a metric of “clean” as any source that results in less than 0.82 metric tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent per megawatt hour of energy. (Carbon dioxide-equivalent is a metric that normalizes other types of greenhouse gas emissions, some of which are more potent, to carbon dioxide.) That standard would disqualify coal but allow most gas. Past legislative proposals have included standards that are twice as strict, but an analysis by Friends of the Earth found that even under those, “fewer than 1% of gas-powered facilities would be excluded from qualifying for the standard.”

Disagreements over whether a RES or CES are preferable aren’t new. In fact, CES policies came out of attempts to compromise in the late 2000s, when they were billed an alternative to a renewable portfolio standard that could include things like “clean coal” and natural gas.

Today, coal is all but dead thanks mostly to market shifts. The fight over these limits is largely one about natural gas, which while less polluting than other energy sources like coal, still results in greenhouse gas emissions when dug up and burned. It’s also the number one contributor to the increase in U.S. carbon pollution in 2019.

“A CES does not need to include fossil gas and it shouldn’t,” said Leah Stokes, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

That could, however, come with one caveat—gas producers could use carbon capture and sequestration technology to suck up their emissions. A recent report from Evergreen Action and Data for Progress that Stokes co-authored lays out a stringent CES that only gives credits to gas if it is paired with carbon capture technology. Existing forms and techniques to capture carbon suck up only 0.1% of global emissions. But technological developments could, in theory, make CCS possible. The vast majority of modeling scenarios to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) also require at least some form of CCS. Scientists also generally disagree about if the world can transition to solely renewable energy by 2030.

Yet CCS falls under what the groups opposed to the CES call “false solutions.” Among the issues are the high costs to build carbon capture facilities and the fact that it fails to address methane emissions and other forms of air pollution tied with natural gas. And further, the groups argue that the mere inclusion of natural gas of any kind in a CES would send a signal to the industry that it’s okay for it to continue writing gas expansion into its business plans.

“If you look at the at the business models that are continuing to be promoted by Shell, BP, and particularly by Exxon, those business models even to this day, show continued growth in natural gas production and consumption and the thing that makes it magically disappear, is CCS,” Caroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law, said.

There’s also, of course, the question of political viability to going 100% renewable. Even with Democrats in control of Congress and the White House, passing policies to decarbonize the grid won’t be easy, let alone a RES. With the filibuster in place, Evergreen Action and Data for Progress have argued that the best way to pass a CES is to use the complex process of reconciliation, which allows a simple majority of the Senate to pass legislation. This would still require conservative Democrats’ support, namely Sen. Joe Manchin, who’s sent mixed signals on whether or not he’d support such legislation. A CES that includes gas, with or without carbon capture, could be more likely to get him on board.

But for the RES advocates, that’s simply too big a compromise to make. Jean Su, energy justice program director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said that’s especially true for frontline communities who live in the communities where natural gas plants, carbon capture pipelines, biomass plants, or other polluting infrastructure are sited.

“We need to shift the conversation from what is feasible to what is necessary. The climate emergency is a ticking time bomb, and we have no time to embrace electricity standards that lock in decades of dangerous gas and reinforce our profoundly racist and ecocidal energy system,” she said.

Ultimately, the difference between CES advocates’ vision and that of RES advocates’ seems to be this question of compromise. While the former are concerned about acting quickly to pass something that could usher in a better yet imperfect energy system, RES advocates fear that buckling on these key issues renders the project too weak and all too easy for the fossil fuel industry to co-opt.

“We believe that Congress is basically going to have one shot at getting this done and that they need to get it done right,” Mitch Jones, policy director of Food and Water Watch, said.

After four years of backsliding under former President Donald Trump, the U.S. is back to increasing its climate ambitions. But there’s a fight brewing over what exactly constitutes zero-carbon energy, showing that challenges decarbonization faces.

President Joe Biden has proposed a clean electricity standard to reduce emissions, and various proposals and bills would create one for the U.S. On Wednesday, though, 650 organizations including Climate Justice Alliance, Greenpeace, Food and Water Watch, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Friends of the Earth sent an open letter to Congress asking it to eschew the clean electricity standard proposals and take another route to clean energy, known as a renewable electricity standard, instead.

If you’re confused, I don’t blame you—the terms “clean” and “renewable” for energy are often used interchangeably. But in this case, while the CES defines non-polluting energy as anything that falls under a certain pollution standard, the RES simply lists out forms of energy that count. The letter calls for a bill that would require the U.S. to solely use renewable sources—defined as wind, solar, and geothermal—to meet its carbon-free electricity needs by 2030. That’s five years ahead of Biden’s current timeline in addition to the only renewables requirement.

“One of the most basic and important questions of climate policy is how you define clean energy,” said Lukas Ross, program manager at Friends of the Earth while noting that “definitions matter.”

Capitol Hill has seen a number of CES proposals. One that the letter specifically cites, the CLEAN Future Act of 2021, sets a metric of “clean” as any source that results in less than 0.82 metric tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent per megawatt hour of energy. (Carbon dioxide-equivalent is a metric that normalizes other types of greenhouse gas emissions, some of which are more potent, to carbon dioxide.) That standard would disqualify coal but allow most gas. Past legislative proposals have included standards that are twice as strict, but an analysis by Friends of the Earth found that even under those, “fewer than 1% of gas-powered facilities would be excluded from qualifying for the standard.”

Disagreements over whether a RES or CES are preferable aren’t new. In fact, CES policies came out of attempts to compromise in the late 2000s, when they were billed an alternative to a renewable portfolio standard that could include things like “clean coal” and natural gas.

Today, coal is all but dead thanks mostly to market shifts. The fight over these limits is largely one about natural gas, which while less polluting than other energy sources like coal, still results in greenhouse gas emissions when dug up and burned. It’s also the number one contributor to the increase in U.S. carbon pollution in 2019.

“A CES does not need to include fossil gas and it shouldn’t,” said Leah Stokes, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

That could, however, come with one caveat—gas producers could use carbon capture and sequestration technology to suck up their emissions. A recent report from Evergreen Action and Data for Progress that Stokes co-authored lays out a stringent CES that only gives credits to gas if it is paired with carbon capture technology. Existing forms and techniques to capture carbon suck up only 0.1% of global emissions. But technological developments could, in theory, make CCS possible. The vast majority of modeling scenarios to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) also require at least some form of CCS. Scientists also generally disagree about if the world can transition to solely renewable energy by 2030.

Yet CCS falls under what the groups opposed to the CES call “false solutions.” Among the issues are the high costs to build carbon capture facilities and the fact that it fails to address methane emissions and other forms of air pollution tied with natural gas. And further, the groups argue that the mere inclusion of natural gas of any kind in a CES would send a signal to the industry that it’s okay for it to continue writing gas expansion into its business plans.

“If you look at the at the business models that are continuing to be promoted by Shell, BP, and particularly by Exxon, those business models even to this day, show continued growth in natural gas production and consumption and the thing that makes it magically disappear, is CCS,” Caroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law, said.

There’s also, of course, the question of political viability to going 100% renewable. Even with Democrats in control of Congress and the White House, passing policies to decarbonize the grid won’t be easy, let alone a RES. With the filibuster in place, Evergreen Action and Data for Progress have argued that the best way to pass a CES is to use the complex process of reconciliation, which allows a simple majority of the Senate to pass legislation. This would still require conservative Democrats’ support, namely Sen. Joe Manchin, who’s sent mixed signals on whether or not he’d support such legislation. A CES that includes gas, with or without carbon capture, could be more likely to get him on board.

But for the RES advocates, that’s simply too big a compromise to make. Jean Su, energy justice program director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said that’s especially true for frontline communities who live in the communities where natural gas plants, carbon capture pipelines, biomass plants, or other polluting infrastructure are sited.

“We need to shift the conversation from what is feasible to what is necessary. The climate emergency is a ticking time bomb, and we have no time to embrace electricity standards that lock in decades of dangerous gas and reinforce our profoundly racist and ecocidal energy system,” she said.

Ultimately, the difference between CES advocates’ vision and that of RES advocates’ seems to be this question of compromise. While the former are concerned about acting quickly to pass something that could usher in a better yet imperfect energy system, RES advocates fear that buckling on these key issues renders the project too weak and all too easy for the fossil fuel industry to co-opt.

“We believe that Congress is basically going to have one shot at getting this done and that they need to get it done right,” Mitch Jones, policy director of Food and Water Watch, said.