EIGHTIES CULT DEPROGRAMMING ORIGINS

Troubled US teens left traumatised by tough love camps

By Kelly-Leigh Cooper

BBC News

As one of the most famous faces of the 2000s, people think they know the story of Paris Hilton. So, when the 40-year-old released a YouTube documentary about her life last year, many were shocked to learn about her decades-long struggle with trauma.

Hilton tearfully recounted how she was woken up by strangers in her bedroom in the middle of the night as a teenager and forcibly taken across the country. She said her unanswered cries for help repeatedly play out in nightmares which make it difficult to sleep.

Her story, though shocking, is not unique. Hilton is one of thousands of American children sent every year by their parents into a private network of "tough love" residential programmes and schools marketed at reforming their behaviour.

No-one knows how many for sure, because nobody is keeping track.

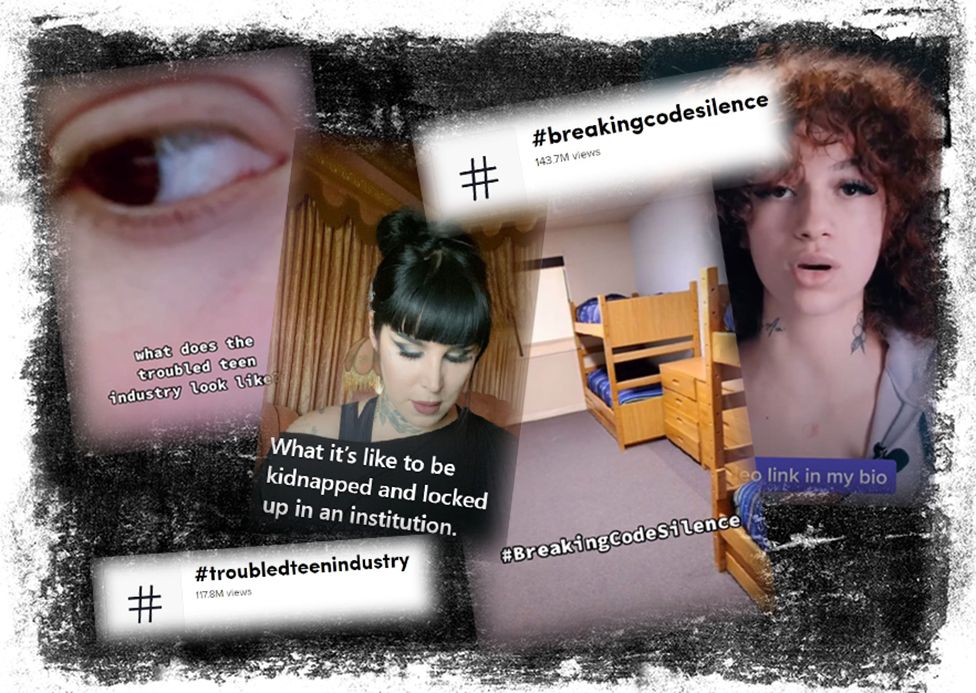

"My parents got me kidnapped and dropped off in the middle of the mountains," 21-year-old Daniel says in a TikTok video watched more than a million times.

As a teenager, Daniel suffered anxiety and depression. He was 15 and had recently come out as gay when he self-harmed so severely that he required hospital care. It was in hospital that he was shaken awake in the middle of the night by two men. They told him the process could be easy or hard - depending on how much he resisted. With little fight left in him, Daniel went with the pair. But when he asked a stranger if he could use a telephone to call his parents on a brief stop for food, he says the escorts threatened him with handcuffs.

Daniel was sent to a wilderness programme in Utah where he spent 77 days living outdoors, hiking miles a day on rations. He vividly remembers feeling cold, hungry and dirty for weeks on end and witnessing others attempt to run away and try to take their own lives. Like many others sent to wilderness programmes, he was then enrolled directly into a long-term facility - this time in Montana - where he would spend another 15 months.

The Troubled Teen Industry (TTI) has become an umbrella term for a wide scope of private residential programmes like these aimed at modifying adolescent behaviour. From boot camps to boarding schools, these facilities are marketed as treatment for a broad range of behavioural and mental health issues including eating disorders, drug use and defiance.

The people who took Hilton and Daniel were from companies specially marketed to families concerned about how their children might react to being enrolled in a programme. These youth transportation services are well-advertised and often come recommended, with parents typically paying a few thousand dollars to have their children taken from their beds and securely dropped off across the country.

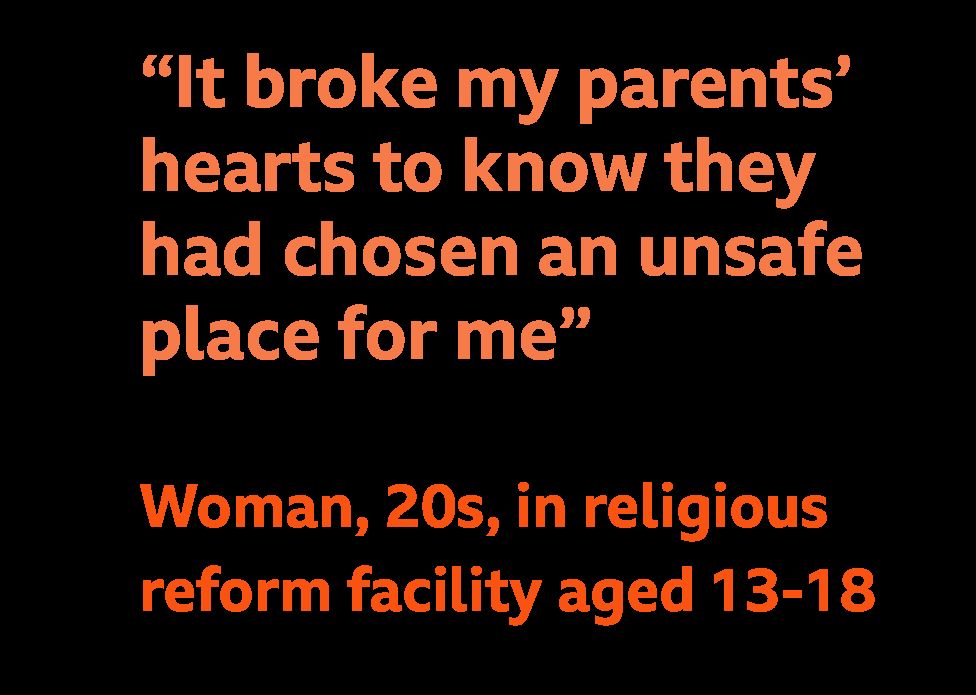

Parents are sometimes referred to the industry by third parties after feeling they have exhausted other means of getting their children help. Programmes sell themselves on high levels of anecdotal success, with testimonials from families and students on their marketing materials and in online reviews describing them as transformative and even life-saving.

But for years, other former residents have been painting a very different picture of their time within these facilities, including in lawsuits and criminal complaints, alleging emotional and physical abuse.

The BBC has spoken to 20 people who identify as troubled teen survivors, aged from 20 to their late 40s, about their experiences within the industry over the last few decades.

Although their individual backgrounds and reasons for being sent away differ, patterns emerge across their accounts and the hundreds more shared in TTI survivor support networks online.

The size of the industry and its yearly turnover of teenagers across the US remains elusive because there is no federal regulator monitoring it.

The US Government Accountability Office was tasked with investigating allegations of neglect and abuse across the industry in 2007, but found it difficult to grasp the national picture due to irregular licensing rules at the state level and ambiguity surrounding the labels facilities use to describe themselves - like boot camps or therapeutic boarding schools.

Their investigators found thousands of allegations of abuse and examined a number of deaths at behavioural programmes across the US and in American-owned businesses operating abroad. Their reports raised concerns about the level of training required of staff as well as what they described as deceptive and questionable marketing practices aimed at parents.

Subsequent hearings in Congress saw parents whose children died within the industry testify.

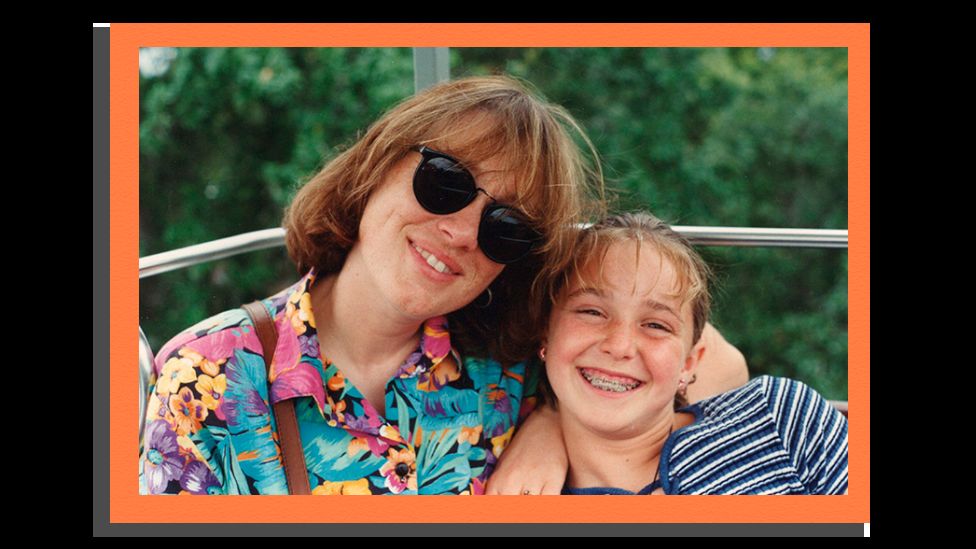

Cynthia Clark Harvey was one of them. Her daughter Erica was just 15 when she died of heatstroke and dehydration on her first full day in a wilderness programme in Nevada in 2002.

Cynthia remembers her daughter as a bright, thoughtful and athletic young girl who had always done well academically until she began suffering from mental health problems aged 14. Her struggles led her to become suicidal and begin experimenting with illegal drugs. When Erica was admitted to hospital and excluded from school, the family felt frightened and out of their depth.

At the time, the situation felt drastic. Erica had been doing better but her psychiatrist recommended that residential treatment could help her path to recovery.

The programme her family chose was well-known and accredited. They felt reassured Erica was in safe hands and would grow from the experience. After weeks of deliberation and planning, they travelled to Nevada under the guise of a family trip with her younger sister. When the deception was revealed, Erica became scared and angry and refused to get out of the car. After a turbulent hours-long group therapy session with other families, she and the other children were taken away.

This was the last time Cynthia and her husband ever saw their daughter alive. By the time they got back home to Arizona the following evening, there was already a message waiting on their answering phone telling them to call. They were told Erica had an accident and staff were performing CPR.

"I don't remember the time frame, but at that point she probably had been dead already for quite some time," Cynthia says.

Erica's obituary could only say that she died hiking in Nevada. Her parents would not find out her cause of death for weeks - and it took years and a lawsuit for them to get records and find out the truth of what happened that day.

Cynthia says they eventually settled with the programme for an undisclosed amount on the condition they could speak freely about the circumstances of their daughter's death. She learned Erica had been pushed to keep hiking as her condition worsened throughout the day. She later testified to Congress about how her daughter's distress had been mistaken for teenage belligerence by staff. Even after Erica fell off the trail into brush and rocks, she did not receive medical help for almost an hour.

The remote location of the trek and a series of blunders in calling help to their location meant it took hours more for an emergency helicopter to arrive and take her to hospital where she was officially declared dead, long past the point her life could have been saved.

Cynthia continues to grapple with regret and grief over what happened and came to connect with other parents who found themselves in the same unimaginable position. No criminal charges were ever filed over her daughter's death but 19 years on, Cynthia continues to speak publicly in favour of industry-wide reform.

The National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (Natsap) - the largest membership association of its kind - appeared on behalf of the industry in the congressional hearings, where it was grilled by lawmakers about the protections and checks in place.

Natsap's website today says it and the industry have changed over time. It emphasises that it has ethical standards in place and requires members to be licensed by their appropriate state agency or a national accrediting body and have therapeutic services overseen by a qualified clinician, though it does not accredit facilities themselves.

Campaigners argue that current levels of oversight are not enough. They say the lack of cohesive national monitoring has allowed bad actors to move around the industry and can enable facilities to rebrand under new names and distance themselves from complaints.

In online networks they have built, people who identify as survivors of the industry connect and offer support across the country - pooling information and resources to track alleged abuses and a revolving door of programmes and staff. One Reddit forum on the topic has more than 20,000 members alone.

While a number of the more controversial programmes and organisations have closed down in recent years, allegations continue to plague the industry. A lot of the stories and experiences former residents recounted to the BBC had a lot in common - whether they got out decades ago or within the last couple of years.

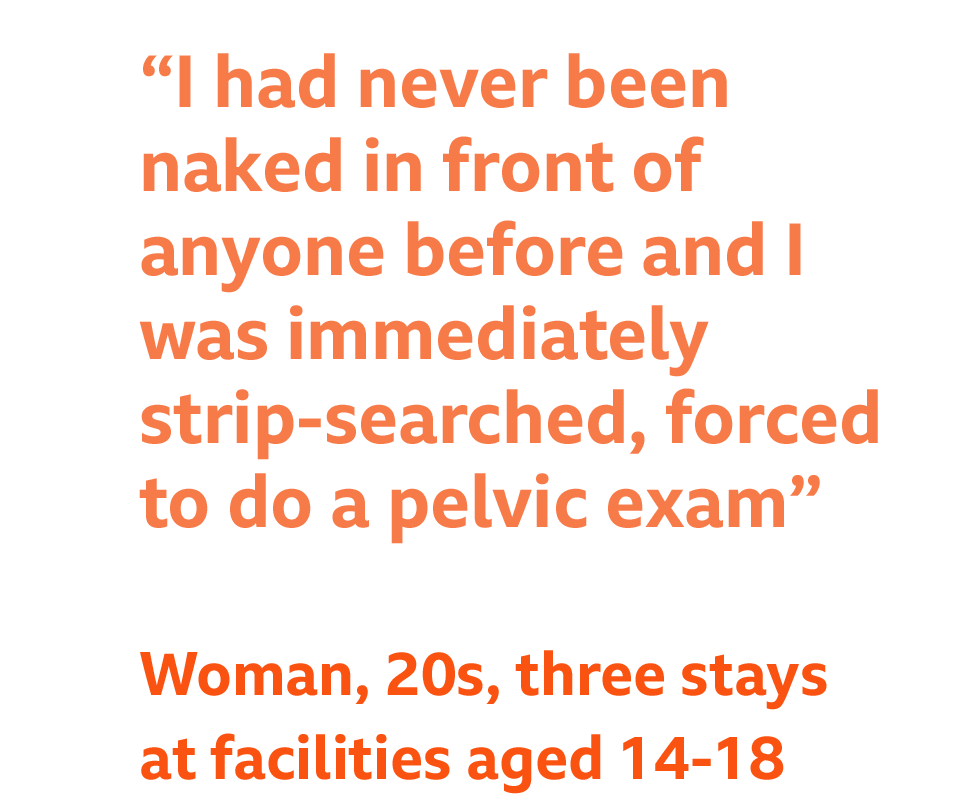

Many described arrival processes that left them feeling degraded and dehumanised. Those taken by transport companies described the process as disorienting and frightening. Some, including sex abuse victims, complained of invasive strip searches and examinations. One person, who was sent due to struggles with depression stemming from gender dysphoria, recounted undergoing a smear test as a virgin aged 14. Others described having their heads shaved and having blood and drugs testing despite having no history of substance abuse themselves.

Some claim to have witnessed and experienced practices like isolation and restraint and say they were also expected to punish and restrain others. Many of the systems they described were based on levels where active participation, including in "attack therapy" sessions where group members are expected to confront and criticise one another, was required to progress and gain basic privileges. Others described arbitrary physical labour, collective punishments and periods of mandated silence which could last weeks.

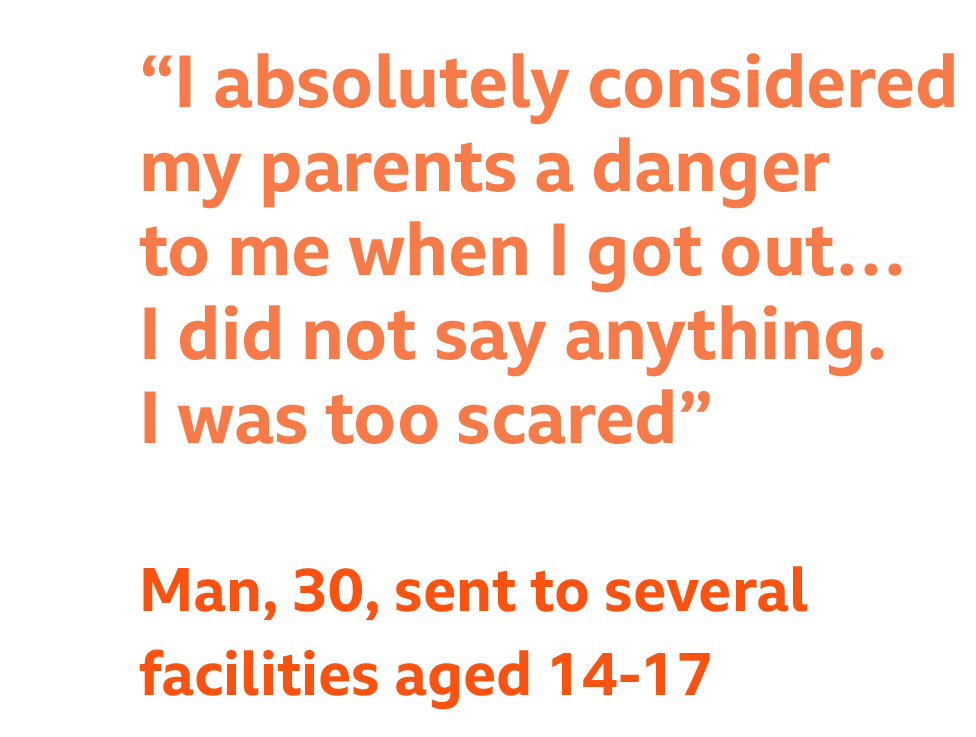

They all described repressive environments with extreme limits and censorship of their contact with the outside world. Many believe their parents were misled about the reality of the programmes they enrolled them in, and describe rules that seeded mistrust between them and their families. Some recounted ongoing damage to relationships and enduring fears of opening up about their experiences, even after leaving, for fear of being sent back or not being believed.

Some told the BBC they witnessed physical violence, self-harm and suicide attempts and many know other residents who took their own lives after leaving. Others have subsequently been diagnosed with conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder and say they continue to suffer long-term social difficulties, including in trusting in others, because of their experience.

In 2006, journalist Maia Szalavitz wrote a book that urged parents to seek evidence-based treatment for children instead of resorting to behavioural modification facilities. Her book traces the origins of many of the methods used in the industry, including confrontational group therapy, to controversial and discredited programmes from decades ago.

Advocates for change say the teenage "tough love" industry, which first began to take off in the 1980s, has been able to endure decades of controversy in part because of social stigma surrounding the issues why parents seek help. It is not uncommon for teenagers to spend years within the system and monthly tuition, sometimes in the thousands, can mount up fast.

Many, including Szalavitz, believe those referring families can exploit or exaggerate fears children will end up dead or incarcerated because of issues like drug abuse. Both her and Dr Kate Truitt, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist who works with former residents, say the trauma experienced at these facilities can actually perpetuate or lead to long-term battles with addiction and abusive relationships.

Many ex-residents, including some the BBC spoke to, say they initially viewed their treatment as justified and even advocated for others to send their children. Some took years to change their opinion of their programme after they reflected on their experiences.

Dr Truitt compares the trauma she has seen in some former residents to that experienced by former members of cults or prisoners of war. She points out that their experiences can be particularly damaging as adolescence is such a critical time for development.

"And because of the type of specific trauma they've endured, most survivors don't feel safe seeking out treatment, because the people who were the treatment providers are the perpetrators," she tells the BBC.

Paris Hilton revealed she had already run away from a number of other placements before she was taken to Provo Canyon in Utah and kept for almost a year before she turned 18.

The documentary This is Paris shows her reuniting with classmates as they go public with their ongoing trauma from alleged experiences of emotional and physical abuse there, including allegations of punishments like solitary confinement.

Provo Canyon remains open. A statement pinned to the top of their website says it was sold to new owners in 2000 and it cannot comment on operations or patient experiences before this time. They also say they do not use methods like seclusion or mechanical restraint now.

Hilton's documentary has been watched almost 30 million times and she has continued vocal advocacy since its release.

This role marks a drastic departure from the persona she built her celebrity brand and business empire around. Although her teenage history was already known among those who went through the same systems, they say having someone as high-profile come forward has helped bring credibility and awareness to the issue.

People within the community say the documentary has empowered some to speak out about their experience for the first time. or has been used to help others, including parents, understand what they went through.

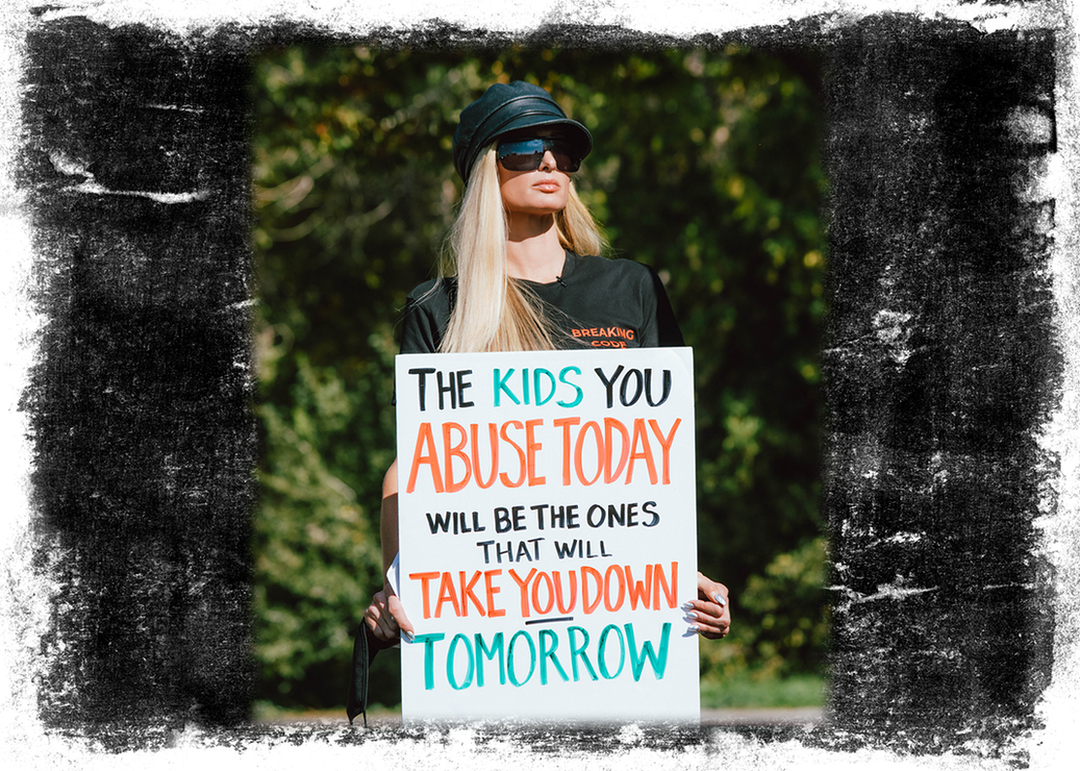

Some former residents have united under the idea of #BreakingCodeSilence, in reference to the periods of mandated social isolation used as a punishment and as a method of control in some facilities.

"One of the rules in many of these programmes is that you couldn't take anyone's phone number or name when you left. So, we were never meant to connect," Katherine McNamara, who went to Provo with Hilton, says about the groups that have emerged on social media. She and some others are now working together on a non-profit to help raise awareness, support those who identify as survivors and advocate for change.

Other celebrities, including Paris Jackson and tattoo artist Kat von D, have been inspired by the documentary to come forward.

Rapper Bhad Bhabie, real name Danielle Bregoli, has called for television personality Dr Phil to apologise for sending her and other teenagers to troubled teen facilities on his popular US show.

It came after another former guest filed a lawsuit alleging she had been punished for reporting an alleged sexual assault by a staff member at the same therapeutic boarding ranch Bregoli was sent to. The facility, which the BBC contacted for a response, has previously denied the allegations against it and disputed their accounts.

Phil McGraw said in an interview he was sad to hear of Bregoli's alleged bad experience but distanced himself and his show from her claims.

K

Younger people, once isolated from their teenage peers because of their experience, are using social media to try and break the stigma. Some have gained huge followings on platforms like TikTok from telling their stories. But none of this is not without personal risk - the BBC has seen legal letters sent to one content creator after they spoke publicly.

Daniel has gained more than 240,000 followers and millions of likes since he started telling his and other people's stories last year. He now gets dozens of messages every day from others who went through similar situations and has had parents contact him to say they've reconsidered plans to send their children away after seeing his videos.

"If my 15-year-old self knew that people were out there fighting for me, I would have felt so relieved," he says about the movement.

In some cases, social media has been a tool for tangible change. One woman, Amanda Householder, used TikTok to spread awareness of allegations surrounding her parents' treatment of girls at a religious boarding ranch they were running in Missouri. Millions viewed her videos and eventually officials closed the school.

Prosecutors later filed more than 100 charges of physical and sexual abuse against the pair, which they have denied.

All this attention has coincided with a cascade of state-level legislative reform.

Householder testified to end religious exemptions in the state of Missouri that stopped even basic oversight of conditions at private religious facilities like the one her parents ran. She described the experience to the BBC as "very cathartic… knowing that maybe in the future kids won't have to go through what we went through" and says she hopes to give evidence in their criminal case.

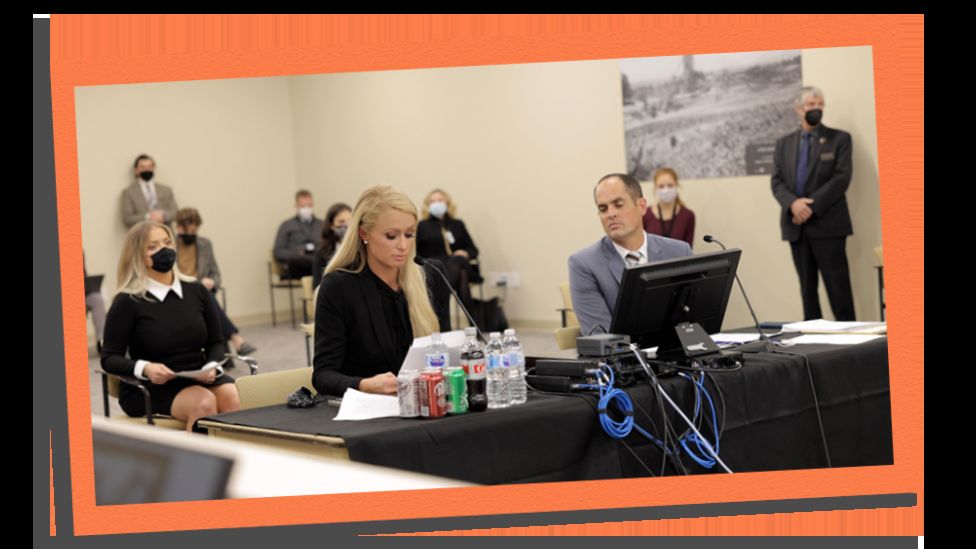

Hilton was part of a group who spoke at a hearing to convince lawmakers to introduce better protections in Utah - the state thought to have the biggest density of troubled teen facilities in the US.

"I don't know if my nightmares will ever go away, but I do know that there are hundreds of thousands of kids going through this, and maybe if I stop their nightmares, it will help me stop mine," she testified.

But for her and others, the real end goal is national change.

Previous attempts to push for federal oversight and regulation have repeatedly faltered in Congress.

But a spokesperson for Democratic Congressman Adam Schiff's office confirmed to the BBC that he is working to update and re-introduce legislation aimed at prohibiting and ending abuse at residential treatment centres and increasing national oversight of such facilities.

Today, Erica Harvey should be in her mid-30s.

"It doesn't get better as the years go on, because it's just more milestones that go by," Cynthia reflects.

It's been well over a decade since she took part in hearings pushing for federal regulation. But against all odds, she remains hopeful.

Cynthia has been emboldened by the momentum building over the last year as more and more have come forward.

"When I first started doing my work after Erica's death, there were survivors out there, but they were not being listened to. And now they're starting to get listened to."