NASA Satellites Find Upper Atmosphere Cooling and Contracting Due to Climate Change

These AIM images span June 6-June 18, 2021, when the Northern Hemisphere noctilucent cloud season was well underway. The colors — from dark blue to light blue and bright white — indicate the clouds’ albedo, which refers to the amount of light that a surface reflects compared to the total sunlight that falls upon it. Things that have a high albedo are bright and reflect a lot of light. Things that don’t reflect much light have a low albedo, and they are dark. Credit: NASA/HU/VT/CU-LASP/AIM/Joy Ng

Since the mesosphere is much thinner than the part of the atmosphere we live in, the impacts of increasing greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, differ from the warming we experience at the surface. One researcher compared where we live, the troposphere, to a thick quilt.

“Down near Earth’s surface, the atmosphere is thick,” said James Russell, a study co-author and atmospheric scientist at Hampton University in Virginia. “Carbon dioxide traps heat just like a quilt traps your body heat and keeps you warm.” In the lower atmosphere, there are plenty of molecules in close proximity, and they easily trap and transfer Earth’s heat between each other, maintaining that quilt-like warmth.

That means little of Earth’s heat makes it to the higher, thinner mesosphere. There, molecules are few and far between. Since carbon dioxide also efficiently emits heat, any heat captured by carbon dioxide sooner escapes to space than it finds another molecule to absorb it. As a result, an increase in greenhouses gases like carbon dioxide means more heat is lost to space — and the upper atmosphere cools. When air cools, it contracts, the same way a balloon shrinks if you put it in the freezer.

This cooling and contracting didn’t come as a surprise. For years, “models have been showing this effect,” said Brentha Thurairajah, a Virginia Tech atmospheric scientist who contributed to the study. “It would have been weirder if our analysis of the data didn’t show this.”

While previous studies have observed this cooling, none have used a data record of this length or shown the upper atmosphere contracting. The researchers say these new results boost their confidence in our ability to model the upper atmosphere’s complicated changes.

The team analyzed how temperature and pressure changed over 29 years, using all three data sets, which covered the summer skies of the North and South Poles. They examined the stretch of sky 30 to 60 miles above the surface. At most altitudes, the mesosphere cooled as carbon dioxide increased. That effect meant the height of any given atmospheric pressure fell as the air cooled. In other words, the mesosphere was contracting.

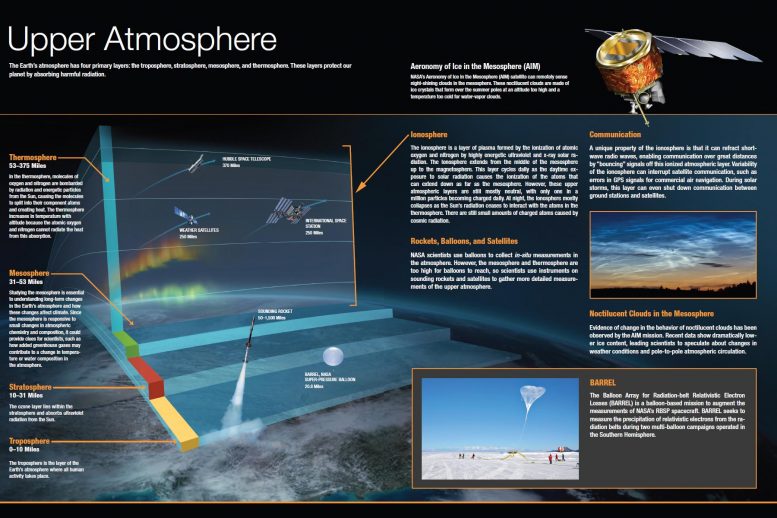

Earth’s Middle Atmosphere

Though what happens in the mesosphere does not directly impact humans, the region is an important one. The upper boundary of the mesosphere, about 50 miles above Earth, is where the coolest atmospheric temperatures are found. It’s also where the neutral atmosphere begins transitioning to the tenuous, electrically charged gases of the ionosphere.

Even higher up, 150 miles above the surface, atmospheric gases cause satellite drag, the friction that tugs satellites out of orbit. Satellite drag also helps clear space junk. When the mesosphere contracts, the rest of the upper atmosphere above sinks with it. As the atmosphere contracts, satellite drag may wane — interfering less with operating satellites, but also leaving more space junk in low-Earth orbit.

This infographic outlines the layers of Earth’s atmosphere. Click to explore in full size. Credit: NASA

The mesosphere is also known for its brilliant blue ice clouds. They’re called noctilucent or polar mesospheric clouds, so named because they live in the mesosphere and tend to huddle around the North and South Poles. The clouds form in summer, when the mesosphere has all three ingredients to produce the clouds: water vapor, very cold temperatures, and dust from meteors that burn up in this part of the atmosphere. Noctilucent clouds were spotted over northern Canada on May 20, kicking off the start of the Northern Hemisphere’s noctilucent cloud season.

Because the clouds are sensitive to temperature and water vapor, they’re a useful signal of change in the mesosphere. “We understand the physics of these clouds,” Bailey said. In recent decades, the clouds have drawn scientists’ attention because they’re behaving oddly. They’re getting brighter, drifting farther from the poles, and appearing earlier than usual. And, there seem to be more of them than in years past.

“The only way you would expect them to change this way is if the temperature is getting colder and water vapor is increasing,” Russell said. Colder temperatures and abundant water vapor are both linked with climate change in the upper atmosphere.

Currently, Russell serves as principal investigator for AIM, short for Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere, the newest satellite of the three that contributed data to the study. Russell has served as a leader on all three NASA missions: AIM, the instrument SABER on TIMED (Thermosphere, Ionosphere, Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics), and the instrument HALOE on the since-retired UARS (Upper Atmospherics Research Satellite).

TIMED and AIM launched in 2001 and 2007, respectively, and both are still operating. The UARS mission ran from 1991 to 2005. “I always had in my mind that we would be able to put them together in a long-term change study,” Russell said. The study, he said, demonstrates the importance of long-term, space-based observations across the globe.

In the future, the researchers expect more striking displays of noctilucent clouds that stray farther from the poles. Because this analysis focused on the poles at summertime, Bailey said he plans to examine these effects over longer periods of time and — following the clouds — study a wider stretch of the atmosphere.