On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog!

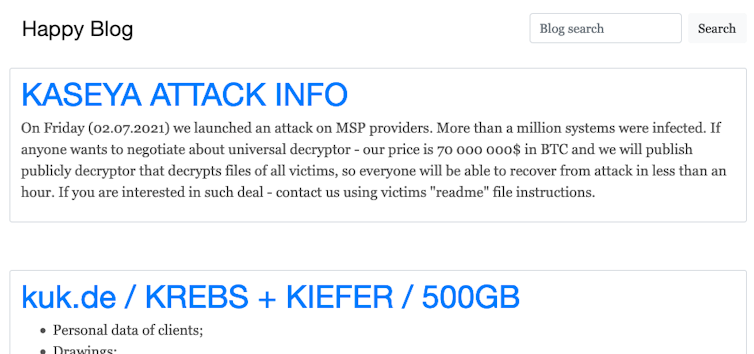

These words from Peter Steiner’s famous cartoon could easily be applied to the recent ransomware attack on Florida-based software supplier Kaseya.

Kaseya provides software services to thousands of clients around the world. It’s estimated between 800 and 1,500 medium to small businesses may be impacted by the attack, with the hackers demanding US$50 million (lower than the previously reported US$70 million) in exchange for restoring access to data being held for ransom.

The global ransomware attack has been labelled the biggest on record. Russian cybercriminal organisation REvil is the alleged culprit.

Despite its notoriety, nobody really knows what REvil is, what it’s capable of or why it does what they does — apart from the immediate benefit of huge sums of money. Also, ransomware attacks often involve vast distributed networks, so it’s not even certain the individuals involved would know each other.

Ransomware attacks are growing exponentially in size and ransom demand — changing the way we operate online. Understanding who these groups are and what they want is critical to taking them down.

Here, we list the top five most dangerous criminal organisations currently online. As far as we know, these rogue groups aren’t backed or sponsored by any state.

DarkSide

DarkSide is the group behind the Colonial Pipeline ransom attack in May, which shut down the US Colonial Pipeline’s fuel distribution network, triggering gasoline shortage concerns.

The group seemingly first emerged in August last year. It targets large companies that will suffer from any disruption to their services — a key factor, as they’re then more likely to pay ransom. Such companies are also more likely to have cyber insurance which, for criminals, means easy moneymaking.

DarkSide’s business model is to offer a ransomware service. In other words, it carries out ransomware attacks on behalf of other, hidden perpetrator/s so they can lessen their liability. The executor and perpetrator then share profits.

Groups that offer cybercrime-as-a-service also provide online forum communications to support others who may want to improve their cybercrime skills.

This might involve teaching someone how to combine distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) and ransomware attacks, to put extra pressure on negotiations. The ransomware would prevent a business from working on past and current orders, while a DDoS attack would block any new orders.

REvil

The ransomware-as-a-service group REvil is currently making headlines due to the ongoing Kaseya incident, as well as another recent attack on global meat processing company JBS. This group has been particularly active in 2020-2021.

In April, REvil stole technical data on unreleased Apple products from Quanta Computer, a Taiwanese company that assembles Apple laptops. A ransom of US$50 million was demanded to prevent public release of the stolen data. It hasn’t been revealed whether or not this money was paid.

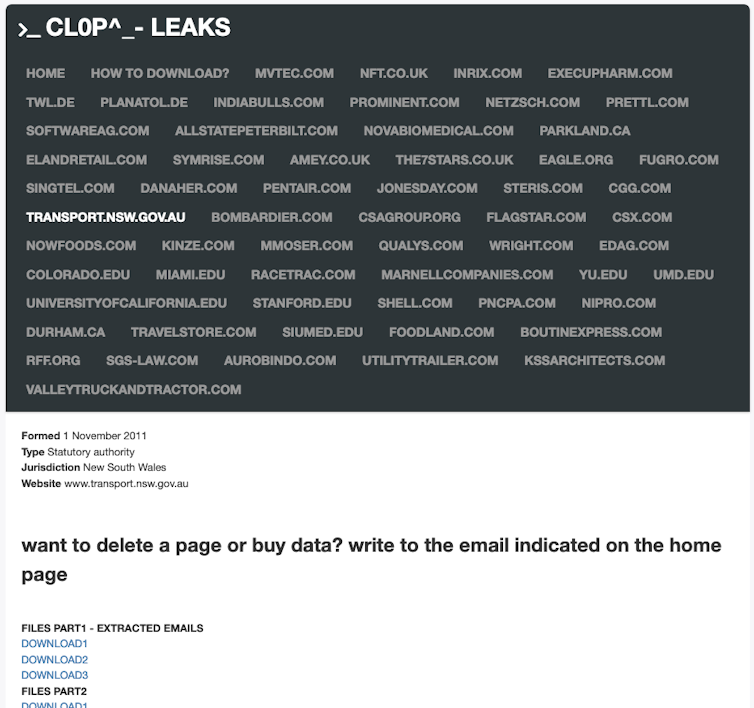

Clop

The ransomware Clop was created in 2019 by a financially-motivated group responsible for yielding half a billion US dollars.

The Clop group’s speciality is “double-extortion”. This involves targeting organisations with ransom money in exchange for a decryption key that will restore the organisation’s access to stolen data. However, targets will then have to pay extra ransom to not have the data released publicly.

Historical examples reveal that organisations which pay a ransom once are more likely to pay again in the future. So hackers will tend to target the same organisations again and again, asking for more money each time.

Syrian Electronic Army

Far from a typical cybercrime gang, the Syrian Electronic Army has been launching online attacks since 2011 to promote political propaganda. With this motive, they have been dubbed a hactivist group.

While the group has links with Bashar al-Assad’s regime, it’s more likely made up of online vigilantes trying to be media auxiliary for the Syrian army.

Their technique is to distribute fake news through reputable sources. In 2013, a single tweet sent by them from the official account of the Associated Press, the world’s leading news agency, had the effect of wiping billions from the stock market.

The Syrian Electronic Army exploits the fact that most people online have a tendency to interpret and react to content with an implicit sense of trust. And they’re a prime example of how the boundaries between crime and terror groups online are less distinct than in the physical world.

FIN7

If this list could contain a “super villain”, it would be FIN7. Another Russian-based group, FIN7 is arguably the most successful online criminal organisation of all time. Operating since 2012, it mainly works as a business.

Many of its operations have been undetected for years. Its data breaches have exploited cross-attack scenarios, wherein the data breach serves multiple purposes. For example, it may enable extortion through ransom while also allowing the attacker to use data against victims, such as by reselling it to a third party.

In early 2017, FIN7 was alleged to be behind an attack targeting companies providing filings to the US Security and Exchange Commission. This confidential information was exploited and used to obtain ransom which was then invested on the stock exchange.

As such, the groups made huge sums of money by trading on confidential information. The insider trading scheme facilitated by hacking went on for many years — which is why it’s not possible to quantify the exact amount of economic damage. But it’s estimated to be well over US$1 billion.

Organised crime vs organised criminals

When it comes to complex criminal organisations, techniques evolve and motives vary.

The way they organise themselves and commit crimes online is very different from your local offline gang. Ransomware can be launched from anywhere in the world, so it’s very difficult to prosecute these criminals. Matters are made even more complicated when several parties coordinate across borders.

It’s no wonder the challenge for law enforcement agencies is significant. It’s crucial that authorities investigating an attack are sure it was indeed perpetrated by who they suspect. But to know this, they need all the help they can get.

Research fellow, Edith Cowan University

Lecturer, Ethical Hacking and Defense, Edith Cowan University

Associate Dean (Computing and Security), Edith Cowan University

Disclosure statement

![Demonstrators clash with police during anti-government protests in Medellin on June 28, 2021 [File: Santiago Mesa/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-06-29T144121Z_857375548_RC2T9O9BOOG0_RTRMADP_3_COLOMBIA-PROTESTS.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

![Plumes of smoke rise from a container ship anchored in Dubai's Jebel Ali port as emergency services try to contain the fire, in Dubai, UAE [WAM/Handout via Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-07T215438Z_1246588380_RC2XFO975QFU_RTRMADP_3_EMIRATES-DUBAI-BLAST.jpg?resize=770%2C513)