Ancient meteorite could reveal the origins of life on Earth

A 4.6-billion-year-old meteorite found in the laying in the imprint of a horseshoe is likely a remnant of cosmic debris left over from the birth of the solar system and could answer questions about how life began on Earth.

It was discovered by Derek Robson, of the East Anglian Astrophysical Research Organisation (EAARO), in a Gloucestershire field, in February, after travelling more than 110 million miles from its primordial home between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter in the Asteroid Belt.

Now, scientists at Loughborough University are analyzing the small charcoal-colored space rock to determine its structure and composition in a bid to answer questions about the early Universe and possibly our own origins.

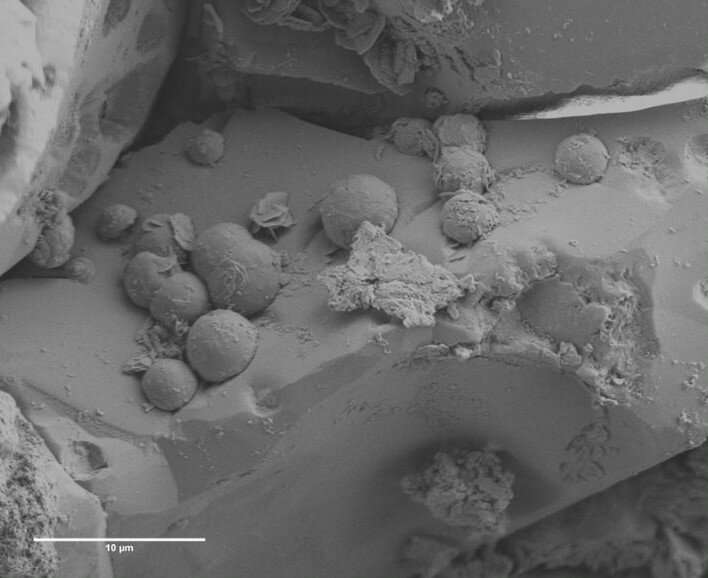

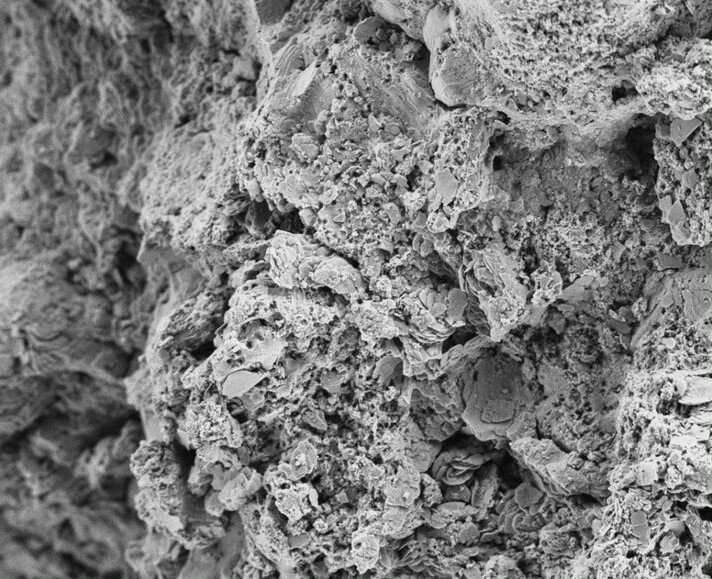

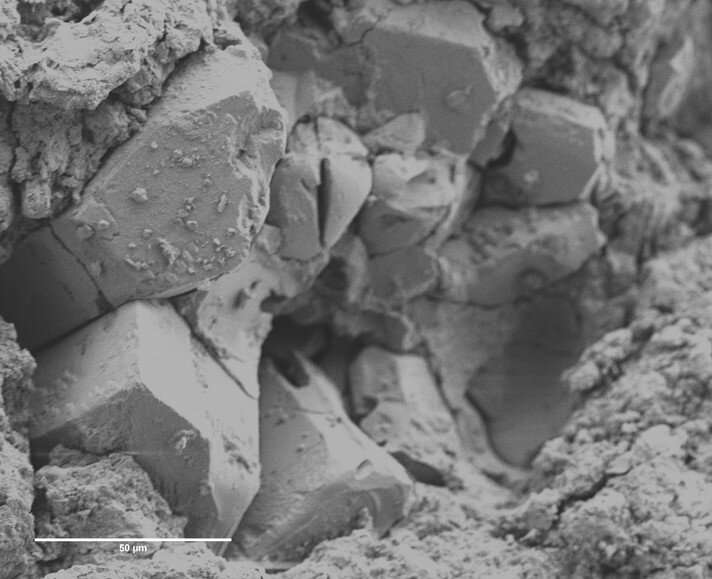

Along with colleagues from EAARO, researchers are using techniques such as electron microscopy to survey the surface morphology at the micron and nanometer scale; and vibrational spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction, which give detailed information about chemical structure, phase and polymorphism, crystallinity and molecular interactions, to determine the structure and composition.

So far, they have found that the incredibly delicate sample, which resembles loosely held-together concreted dust and particles, never underwent the violent cosmic collisions that most ancient space debris experienced as it smashed together to create the planets and moons of our solar system.

"The internal structure is fragile and loosely bound, porous with fissures and cracks," said Shaun Fowler—a specialist in optical and electron microscopy at the Loughborough Materials Characterisation Centre (LMCC).

"It doesn't appear to have undergone thermal metamorphosis, which means it's been sitting out there past Mars, untouched, since before any of the planets were created meaning we have the rare opportunity to examine a piece of our primordial past.

"The bulk of the meteorite is comprised of minerals such as olivine and phyllosilicates, with other mineral inclusions called chondrules, which, for example, can be minerals such as magnetite or calcite.

"But the composition is different to anything you would find here on Earth and potentially unlike any other meteorites we've found—possibly containing some previously unknown chemistry or physical structure never before seen in other recorded samples."

The ancient rock is a rare example of a carbonaceous chondrite, a type of meteorite which often contains biological material. Fewer than 5% of meteorites which fall to Earth belong to this classification.

Identifying organic compounds would support the idea that early meteorites carried amino acids—the building blocks of life—to supply the Earth's primordial soup where life first began.

"Carbonaceous chondrites contain organic compounds including amino acids, which are found in all living things," said Director of Astrochemistry at EAARO Derek Robson who found the meteorite and who will soon join Loughborough University as an academic visitor for collaborative research.

"Being able to identify and confirm the presence of such compounds from a material that existed before the Earth was born would be an important step towards understanding how life began."

Professor Sandie Dann, of the Chemistry Department in the School of Science, first worked with Derek in 1997 and has kept in touch with him regularly since.

She said: "It's a scientific fairy-tale. First your friend tracks a meteorite, then finds it and then gifts a bit of this extra-terrestrial material to you to analyze.

"At this stage, we have learned a good deal about it, but we've barely scratched the surface.

"There is huge potential to learn about ourselves and our solar system—it's an amazing project to be part of."

Jason Williams, Managing Director of EAARO, added: "One of EAARO's primary objectives is to open the doors of science and technology to those who may not get the opportunity.

"Derek and I felt our new find could help us further these objectives by opening up research opportunities in meteoritical science.

"We carefully chose Loughborough, along with University of Sheffield, a number of commercial partners, and a handful of overseas specialists to work with us on this exciting project as we continue to excite and inspire people young and old by promoting and encourage space research and STEM subjects to a wider community."