Hundreds of workers are on strike at the Frito-Lay plant in Topeka, Kansas. Many of them are working 12-hour days, seven days a week, and some haven’t had a day off in five months — conditions that are literally killing them.

At the Frito-Lay plant in Topeka, Kansas, production has only increased during the pandemic. (Justice for Frito Lay)

At the Frito-Lay production plant in Topeka, Kansas, workers are subjected to something called “suicides,” shifts in which they come in for eight hours, are forced to work four more hours, and then are called in four hours early, leaving them only eight hours off between shifts. This is how the company forces overtime to the point that many of those workers say they work twelve hours a day, seven days a week, with some not having had a day off in five months, weekends included.

“The company recently sent us a letter saying those shifts are called ‘squeeze shifts,’ but none of us has heard that term before,” says Samuel Huntsman, who has worked at the plant for three years. “I think they’re just trying to make it sound better.”

What prompted the letter was workers’ willingness to speak out about the anxiety that pervades their shop, one of the reasons that they are now on a strike that is entering its third week. The plant employs some 850 people, and workers have spoken of the deleterious effects of such inhumane working conditions.

As Mark McCarter, a fifty-nine-year-old palletizer and union steward at the plant who has worked there for thirty-seven years, told Vice, “It seems like I go to one funeral a year for someone who’s had a heart attack at work or someone who went home to their barn and shot themselves in the head or hung themselves.”

“Forced overtime interferes with your health and your household,” explains Huntsman. It leads to fights on the shop floor, too, he adds, with workers “getting in arguments because they are so cranky and mad and tired.” Others at the plant have spoken of divorces caused by the schedules, in addition to the suicides. Workers say they have urged Frito-Lay to hire new workers to lighten the load, but that the company hasn’t budged.

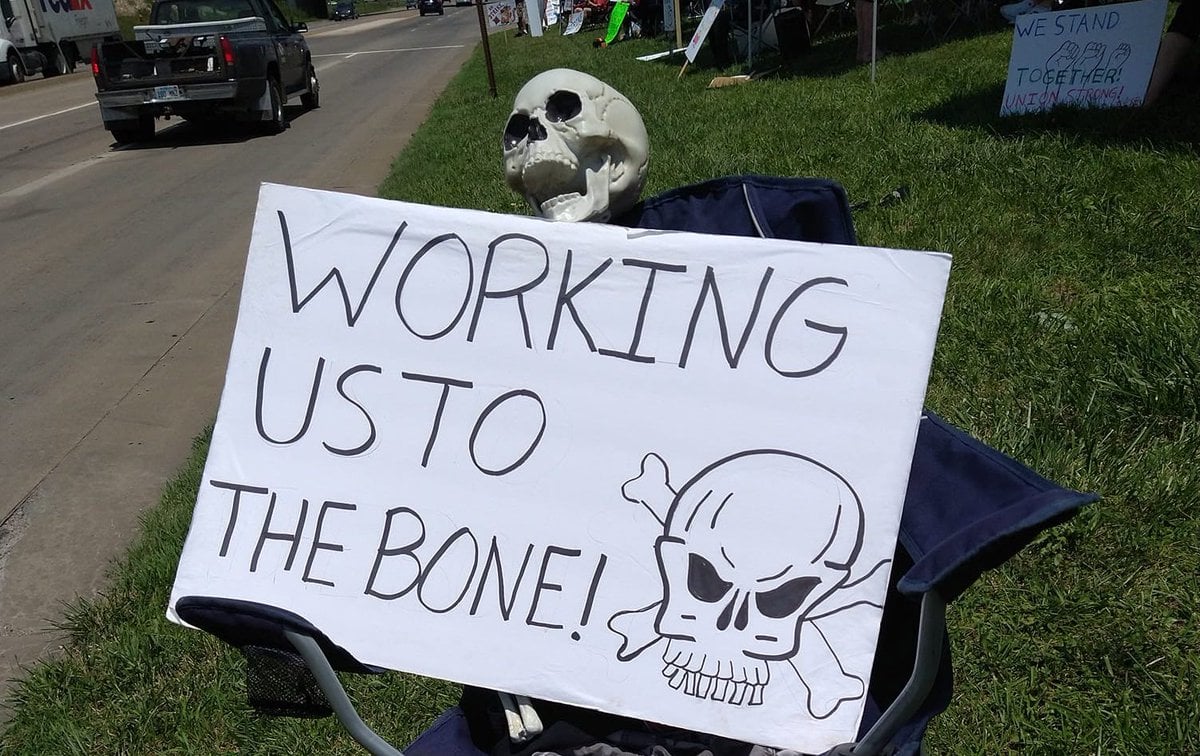

And workers’ mental health isn’t their only concern. “When a coworker collapsed and died, you had us move the body and put in another coworker to keep the line going,” writes Cherie Renfro, one of the striking workers, in an open letter to Frito-Lay. The company says it “wholly rejects” that allegation, but Renfro is not the only one who has raised it. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is currently investigating an incident that took place in May at the facility, and has previously fined the plant for cases involving amputation and vehicular accidents. No wonder workers set up a skeleton on the picket line with a sign that reads, “Working us to the bone.”

At the Topeka plant, production has only increased during the pandemic; whereas people were used to working overtime around holidays, they say they are now being pushed to their limits year-round as people across the United States upped their intake of the products made, packaged, and shipped out of Topeka: Lay’s potato chips, Tostitos, Cheetos, SunChips, Fritos, Doritos. The result for the workers was misery; for the company, it was more than $4.2 billion in sales, partially responsible for a 14 percent spike in revenue for its parent company, PepsiCo, a Fortune 500 company with a rising stock.

Despite such good fortune, the company continues to treat workers with less care than it treats its machines — there is no concern for upkeep, only for wringing every last bit of labor from their bodies, even if it kills them. To be worked to death to produce potato chips — it is hard to imagine something so insulting and cruel.

The company’s latest proposed contract offers a mere 2 percent wage increase this year and caps the number of hours someone can be forced to work at sixty per week. It is not nearly enough. Many of the workers make under $20 an hour and haven’t seen a raise in a decade — the company prefers small bonuses that keep the pay scale from rising. Among the growing number of manufacturing facilities and warehouses in the area — Home Depot and Target distribution centers, a Goodyear tire plant, a Mars chocolate facility, and a Bimbo bread bakery among them — pay at the Frito-Lay plant is low, and turnover is high. As Mark Benaka, business manager for Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers (BCTGM) Local 218, which represents some six hundred of the Topeka workers, tells Labor Notes, “Between all those industries, Frito-Lay sits at the bottom of the ladder as far as wage scales.” This is why the workers are demanding a minimum of $1 to $2-an-hour raises.

Recent matters have only intensified the problems at the plant. For instance, while management could stay home during the pandemic, workers could not. Some say they received no hazard pay or bonuses, while others speak of receiving a meager extra $100 a week, but only for a few weeks. Now, during a particularly hot summer, the plant lacks air-conditioning. According to McCarter, “At 7 a.m., our warehouse is 100 degrees. We don’t have air conditioning. We have cooks in the kitchen on the fryers that are 130 or 140 degrees, making chips and sweating like pigs. Meanwhile, the managers have AC.”

These conditions are what led workers, after holding informational pickets and voting down previous contract offers, to withdraw their labor. In late June, workers voted 353 to 30 in favor of authorizing a strike. The work stoppage began at midnight on July 5.

Mandatory overtime is an issue at other shops represented by BCGTM, which has some seventy-thousand members; workers elsewhere say they, too, are being forced to work every day, and over sixty hours a week. While some workers want to work more hours to make an overtime rate, mandatory hours of this sort are unconscionable. It is always hard to organize in a right-to-work state, but it is shameful that a union shop has reached this state, and a situation that suggests, at best, internal tensions within BCGTM over how to win on this issue.

In a statement on the strike, BCGTM president Anthony Shelton, who took over the position after the previous president, David Durkee, passed away last year, said that workers at the Frito-Lay plant “do not have enough time to see their family, do chores around the house, run errands, or even get a healthy night’s sleep. This strike is about working people having a voice in their futures and taking a stand for their families.” “The union has repeatedly asked the company to hire more workers, and yet despite record profits, Frito-Lay management has refused this request,” he added.

As the strike enters its third week, workers say it has strong support, both in the community and, as it gains attention, nationally — but most importantly, among the shop’s workforce. Around half the workforce is out on strike — around six hundred of the workers in the right-to-work state are Local 218 members — a number Huntsman says is growing by the day. Although the company says production continues, some workers say that is a ruse.

“It’s psychological warfare — they’re trying to demoralize and dispirit the men and women of the union in the hopes we’ll come groveling back for whatever crumbs they offer us,” Monk Drapeaux-Stewart, a box-drop technician at the plant, tells Labor Notes. “There’s been no smoke, no steam, no nothing, no sign of production at all” coming from the plant either, he adds. Huntsman estimates the company began getting enough scab labor — out-of-town workers, workers from other Frito-Lay plants, and bosses from the company — late last week to start running one or two of the plant’s kitchens at reduced hours, but he believes production remains far below the usual level.

While the local hasn’t issued a formal call for a boycott, some workers at the Topeka plant are calling for exactly that. Per McCarter, the palletizer: “We would rather nobody buy any Frito-Lay products — Fritos, Doritos, Tostitos, Funyuns, Cheetos, all those — while we’re on strike. We make all of those in Topeka, Kansas. We also would rather nobody buys PepsiCo products while we’re on the line. PepsiCo is the owner of Frito-Lay.” With support for such a call present on the picket line, anyone concerned with the ability of their fellow human being to survive should abide by that request; these workers are fighting for their lives, and they need all the support they can get. Workers are also asking the public to call PepsiCo’s board of directors to urge them to bargain a fair and reasonable contract. A local magazine, 785, has also set up a fund to help pay strikers’ water-utility bills.

Negotiations resumed today, the first bargaining session since the strike began two weeks ago. Workers are hopeful but firm about what they need. Aside from their demands for a significant raise, caps on forced overtime, and a change in disciplinary procedures, Huntsman hopes the workers can win paid paternity leave. While Frito-Lay offers paid leave to workers at its nonunion shops, it does not do so at the Topeka plant. As for why that is, the reason is obvious.

“They’re punishing us because they want the union gone,” says Huntsman. In other words, the company wants to convince workers that only without a union can they win maternity and paternity leave, an insidious strategy for undermining collective power used by employers to push workers to decertify their union and, in doing so, give up their seat at the table.

But with support for the strike growing, the workers in Topeka are undaunted. As Reyna Corpus, one of the striking Frito-Lay workers, explains in displaying her sign on the picket line, which shows a black boot looming over people: “The boot represents Frito-Lay, and under the boot is the people standing, which is us, the workers, the union.” “We can stop the boot,” she says, “with the help of the community, with all the people in the union — yeah, we can do it, we can stop the boot.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alex N. Press is a staff writer at Jacobin. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Vox, the Nation, and n+1, among other places.