The History of Systemic Racism that CRT

Opponents Prefer to Hide

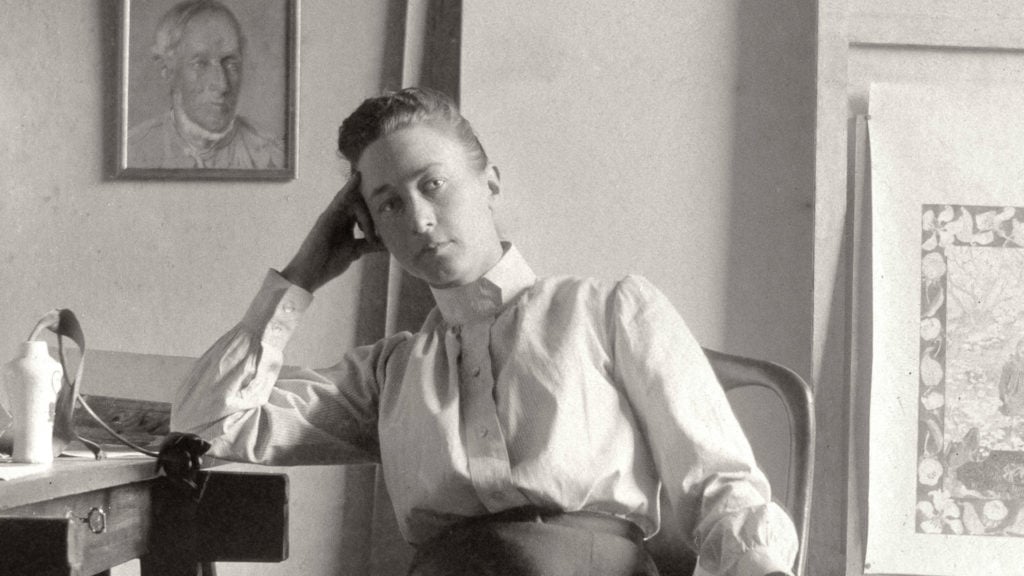

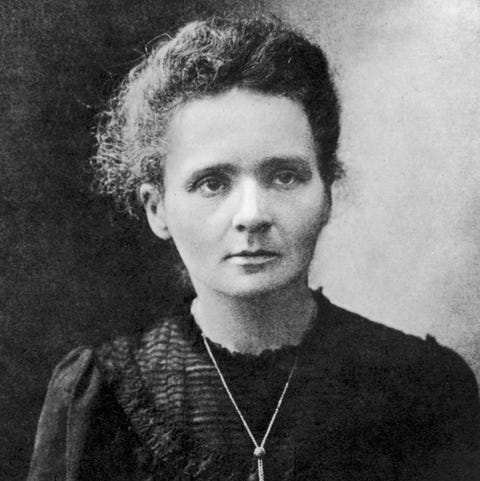

Illustration of the importation of captive Africans at Jamestown in 1619, Howard Pyle, 1910. Library of Congress.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has become a lightning rod for conservative ire at any discussion of racism, anti-racism, or the non-white history of America. Across the country, bills in Republican-controlled legislatures have attempted to prevent the teaching of CRT, even though most of those against CRT struggle to define the term. CRT actually began as a legal theory which held simply that systemic racism was consciously created, and therefore, must be consciously dismantled. History reveals that the foundation of America, and of systemic racism, happened at the same time and from the same set of consciously created laws.

Around the 20th of August, 1619, the White Lion, an English ship sailing under a Dutch flag, docked off Old Point Comfort (near present-day Hampton), in the British colony of Virginia, to barter approximately 20 Africans for much needed food and supplies. The facts of the White Lion’s arrival in Virginia, and her human cargo, are generally not in dispute. Whether those first Africans arriving in America were taken by colonists as slaves or as indentured servants is still debated. But by the end of the 17th century, a system of chattel slavery was in place in colonial America. How America got from uncertainly about the status of Africans, to certainty that they were slaves, is a transition that highlights the origins of systemic racism.

Three arguments have been put forth about whether the first Africans arriving in the colonies were treated as indentured servants or as slaves. One says that European racism predisposed American colonists to treat these Africans as slaves. Anthony and Isabella, for example, two Africans aboard the White Lion, were acquired by Captain William Tucker and listed at the bottom of his 1624/25 muster (census) entry, just above his real property, but below white indentured servants and native Americans.

A second argument counters that racism was not, at first, the decisive factor but that the availability of free labor was. “Before the invention of the Negro or the white man or the words and concepts to describe them,” historian Lerone Bennett wrote, “the Colonial population consisted largely of a great mass of white and black [and native] bondsmen, who occupied roughly the same economic category and were treated with equal contempt by the lords of the plantations and legislatures.”

In this view, slavery was not born of racism, but racism was born of slavery. Early colonial laws had no provisions distinguishing African from European servants, until those laws began to change toward the middle of the 17th century, when Africans became subject to more brutal treatment than any other group. Proponents of this second argument point to cases like Elizabeth Key in 1656, or Phillip Corven in 1675, Black servants who sued in different court cases against their white masters for keeping them past the end of their indentures. Both Key and Corven won. If slavery was the law, Key and Corven would have had no standing in court much less any hope of prevailing.

Still, a third group stakes out slightly different ground. Separate Africans into two groups: the first generation that arrived before the middle of the 17th century, and those that arrived after. For the first generations of Africans, English and Dutch colonists had the concept of indefinite, but not inheritable, bondage. For those who came after, colonists applied the concept of lifetime, inheritable bondage. Here, the 1640 case of John Punch, a Black man caught with two other white servants attempting to run away, is often cited. As punishment, all the men received thirty lashes but the white servants had only one-year added to their indentures, while John Punch was ordered to serve his master “for the time of his natural life.” For this reason, many consider John Punch the first real slave in America. Or was he the last Black indentured servant?

Clearly these cases show the ambiguity, or “loopholes,” of the system separating servitude from slavery in early America. What is also clear is that one by one these loopholes were closed through conscious intent of colonial legislatures. In this reduction of ambiguity over the status of Africans, the closure of loopholes between servitude and slavery, are the roots of systemic racism.

Maryland enacted a first-of-its-kind law in 1664, specifically tying being Black to being a slave. “[A]ll Negroes or other slaves already within the Province And all Negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the Province shall serve Durante Vita.” Durante Vita is a Latin phrase meaning for the duration of one’s life.

Another loophole concerned the status of children. Colonial American law was initially derived from English common law, where the status of child (whether bound or free) followed the status of the father. But adherence to English common law posed problems in colonial America, such as revealed in the 1630 case of Hugh Davis, a white man sentencing to whipping “for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a negro...” Whipping proved no deterrent for such interracial unions between a free European and a bound African. If English common law was followed, then the child of such a liaison would be free. So, in the years following Davis’ whipping the legislatures in Maryland and Virginia enacted statutes that the status of the child, whether slave or free, followed that of the mother.

But closing this loophole assumes that only the sexual exploits of European men needed containing. The famous, and well-documented case of Irish milkmaid, Molly Welsh, who worked off her indentures in Maryland, shows the reverse actually happened as well. Welsh purchased a slaved named Banna Ka, whom she eventually freed, then married. They had a girl named Mary, who was free. Mary married a runaway slaved named Thomas, and they had a boy named Benjamin, who was also free. And Benjamin Banneker, a clockmaker, astronomer, mathematician, and surveyor, became an important figure in African American history, having authored a letter to Thomas Jefferson lamenting the lofty ideals of liberty and equality contained in the nation’s founding documents were not extended to all citizens regardless of color.

Closing the religious exemption was another way in which colonial legislatures sought to separate Blacks from whites, and force slavery only on people of African descent. One of the reasons Elizabeth Key prevailed in court was that she asserted she could not be held in slavery as a Christian. In fact, there was a widespread belief in early America that Christians holding other Christians in slavery went against core biblical teachings.

Most first generation Africans in colonial America came from the Angola-Congo region of West Africa, first taken there by the Portuguese. Christianity was well-known, and practiced by Africans in these regions as early as the 15th century. So, many Africans destined for slavery, or indentured servitude in America, were already baptized, or were christened by priests aboard Portuguese slave trading vessels.

Colonial legislatures got busy. Maryland updated the 1664 law, cited above, with a 1671 statute that specifically carved out a religious exception for people of African descent. Regardless of whether they had become Christian, or received the sacrament of baptism, they would “hereafter be adjudged, reputed, deemed, and taken to be and remain in servitude and bondage” forever. Acts like this led to a tortured, convoluted American Christianity, developed to support slavery, and this legacy of racism within American Christianity continues to this day.

Apprehension of runaway servants and slaves was still another area in which colonial legislatures targeted people of color for differential, oppressive treatment. While granting masters the right to send a posse after runaways, a 1672 Virginia statute called “An act for the apprehension and suppression of runawayes, negroes and slaves,” granted immunity to any white person who killed or wounded a runaway person of color while in pursuit of them. It read:

“Be it enacted by the governour, councell and burgesses of this grand assembly, and by the authority thereof, that if any negroe, molatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, runaway and shalbe persued by warrant or hue and crye, it shall and may be lawfull for any person who shall endeavour to take them, upon the resistance of such negroe, mollatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, to kill or wound him or them soe resisting.”

Acts like this became the basis for slave patrols, and for the police forces that arose from them. Today, we still deal with the consequences of “qualified immunity,” stemming from ideas like these enacted in 1672, which shield police from prosecution in cases of violence and brutality, especially against people of color.

Protection of southern rights even found its way into the Constitution. The Second Amendment protects the right of militias (a polite term for “slave patrols”) to organize and bear arms. The Fugitive Slave Clause (never repealed) guaranteed southern slaveholders that their slaves apprehended in the North would be returned. Even the Interstate Commerce Clause allowed Southerners traveling North with their slaves assurances those slaves would not automatically become free by setting foot in states that outlawed slavery.

Though enacted centuries ago, the laws cited above are representative of the many laws that came to define American jurisprudence, and have at their core, the repression and oppression of Black Americans, and other people of color. This is why Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, writing for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857, handed down a 7-2 verdict in the Dred Scott case, with the words that Blacks had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” This is why critical race theory states that systemic racism was consciously created, as these laws and their enforcement show they were.

But this is also why Republican legislators and their supporters lump anything and everything having to do with diversity, equity, and inclusion into the box of critical race theory, then try to keep it out of schools and public institutions. They’re afraid of Americans being told the truth: that the foundation of America, and of systemic racism, happened at the same time and from the same consciously created laws. In this way, these individuals are actually living proof of the validity of critical race theory, because they seek to consciously enact laws today which perpetuate the racial inequality established by laws enacted hundreds of years ago.