We have to pay the price’: Oslo’s plan to turn oil wealth into climate leadership

The mayor of the Norwegian capital argues that the ‘moral’ duty to cut emissions from burning waste can be met by carbon capture

The Fortum Oslo Varme incinerator burns 400,000 tonnes of waste a year.

Photograph: Einar Aslaksen

Jillian Ambrose

Jillian Ambrose

THE GUARDIAN

Wed 28 Jul 2021

The city of Oslo was built on wealth generated by the North Sea, which for decades has produced billions of barrels of oil and gas. But Oslo now hopes to lead Norway’s transformation from one of the world’s largest exporters of fossil fuels to a global green pioneer.

For Raymond Johansen, Oslo’s governing mayor, helping to lead global efforts to tackle the climate cisis is both a pragmatic economic response to Norway’s declining fossil fuel industries, and a moral obligation to provide solutions for a crisis it helped to create.

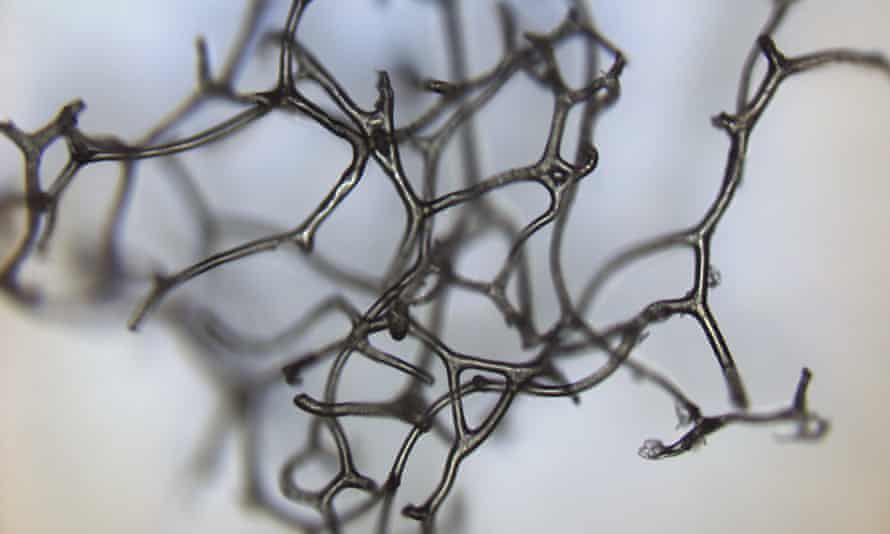

At the heart of Johansen’s plan stands an otherwise unassuming industrial waste incinerator. The Oslo Varme plant, on the outskirts of the capital, generates heat and electricity by burning rubbish and is by far Oslo’s biggest carbon polluter. But the plant was shortlisted earlier this year among schemes competing for €1bn in support from the EU’s low-carbon innovation fund. Johansen says Oslo wants to turn the incinerator into a blueprint for how cities across Europe can cut carbon emissions while tackling their waste.

“It is one of my biggest ambitions as the leader of Oslo,” says Johansen. “We are small enough and big enough at the same time to provide a test bed for western Europe.”

The city’s plan is to retrofit the waste plant with carbon capture technology to trap its emissions before they can enter the atmosphere and contribute to global heating. The plant burns 400,000 tonnes of non-recyclable waste a year, of which between 50,000 to 100,000 tonnes comes from the UK’s household rubbish. Incinerators make up 15% of Oslo’s carbon emissions.

Wed 28 Jul 2021

The city of Oslo was built on wealth generated by the North Sea, which for decades has produced billions of barrels of oil and gas. But Oslo now hopes to lead Norway’s transformation from one of the world’s largest exporters of fossil fuels to a global green pioneer.

For Raymond Johansen, Oslo’s governing mayor, helping to lead global efforts to tackle the climate cisis is both a pragmatic economic response to Norway’s declining fossil fuel industries, and a moral obligation to provide solutions for a crisis it helped to create.

At the heart of Johansen’s plan stands an otherwise unassuming industrial waste incinerator. The Oslo Varme plant, on the outskirts of the capital, generates heat and electricity by burning rubbish and is by far Oslo’s biggest carbon polluter. But the plant was shortlisted earlier this year among schemes competing for €1bn in support from the EU’s low-carbon innovation fund. Johansen says Oslo wants to turn the incinerator into a blueprint for how cities across Europe can cut carbon emissions while tackling their waste.

“It is one of my biggest ambitions as the leader of Oslo,” says Johansen. “We are small enough and big enough at the same time to provide a test bed for western Europe.”

The city’s plan is to retrofit the waste plant with carbon capture technology to trap its emissions before they can enter the atmosphere and contribute to global heating. The plant burns 400,000 tonnes of non-recyclable waste a year, of which between 50,000 to 100,000 tonnes comes from the UK’s household rubbish. Incinerators make up 15% of Oslo’s carbon emissions.

Raymond Johansen, governing mayor of Oslo.

Photograph: City of Oslo/Oslo municipality

If it succeeds the project could play a major role in Oslo’s goal to cut its carbon emissions by 95% by 2030 compared to levels in 2009, says Johansen. But it could also be the first step in developing the technology for deployment at similar waste-to-energy plants across Europe. At its most ambitious the project hopes to provide a foothold for Norway’s wider plan to create a full-scale carbon capture chain, capable of storing Europe’s emissions permanently under the North Sea.

“From both an ethical and a moral point of view, I think it’s important that we are willing to contribute [to climate efforts] on a more advanced scale and develop the new technologies we need,” Johansen says.

Norway believes that it can build on its half-century legacy of piping fossil gas from the North Sea to Europe by doing the same in reverse for carbon emissions. The Northern Lights carbon capture project plans to ship liquid CO2 from industrial sites fitted with carbon capture technology to an onshore terminal on the Norwegian west coast. From there, the liquified carbon will be transported by pipeline to a storage location under the North Sea, where it will be stored permanently.

“A rich oil- and gas-dependent country like Norway is to some extent obliged to develop such technology and make it more available to the rest of Europe. We have to do that. We have to pay that price,” Johansen says.

The €700m cost of the Oslo Varme incinerator carbon capture project would require EU funding of €300m, in addition to investments from the Norwegian government and the plant’s joint owners, the Oslo municipality and utility company Fortum. Beyond the cost, there are concerns over its climate credentials too.

Johansen says some of the scepticism derives from fears that carbon capture will make governments “more lazy when we come to recycling waste, reusing materials”. Others fear that relying on carbon capture technology – which typically traps 80-95% of emissions – will give a licence to maintain the world’s carbon-intensive status quo at the expense of pursuing cleaner alternatives.

Friends of the Earth Europe has called Norway’s carbon capture and storage plans “a spoke in the wheel of the energy transition” and warned that relying on the technology could delay a full-scale commitment to energy efficiency and renewables.

Johansen says both waste incineration and carbon capture will still be needed as “last resort” approaches to tackling pollution – even after rigorous efforts to opt for renewable and recycled materials while consuming less overall. The mayor claims that between 20% and 25% of Europe’s waste would be destined for landfill even after “quite advanced recycling”, where it would create far more carbon emissions than in an incineration plant.

For Johansen, the inevitable criticisms are dwarfed by the scale of the potential benefits in tackling the twin challenges of waste pollution and rising carbon emissions. It does not, he insists, mean that Norway can ignore the need for a more fundamental economic shift away from fossil fuels and towards sustainable growth.

“From a long-term perspective we must dismantle our own oil and gas industry,” he says. “It will take a lot of time because we are so dependent on the industry for labour. So many people work in the fossil fuel industry that it means many traditional working-class people are more and more sceptical about some of the green parties’ arguments because they feel they are taking away their jobs.”

The new industrial opportunities presented by carbon capture offer what the Johansen refers to as “normal jobs, for normal people”, which are within reach without the need for a university degree.

Johansen trained as a plumber before going into politics for Norway’s Labour party. “One of the most important things for me is to avoid the shift to green becoming a middle-class project,” he says. “We need to get all people on board, and they need to see that there is a prosperous future for them as well. It’s a new kind of industrialisation.”

If it succeeds the project could play a major role in Oslo’s goal to cut its carbon emissions by 95% by 2030 compared to levels in 2009, says Johansen. But it could also be the first step in developing the technology for deployment at similar waste-to-energy plants across Europe. At its most ambitious the project hopes to provide a foothold for Norway’s wider plan to create a full-scale carbon capture chain, capable of storing Europe’s emissions permanently under the North Sea.

“From both an ethical and a moral point of view, I think it’s important that we are willing to contribute [to climate efforts] on a more advanced scale and develop the new technologies we need,” Johansen says.

Norway believes that it can build on its half-century legacy of piping fossil gas from the North Sea to Europe by doing the same in reverse for carbon emissions. The Northern Lights carbon capture project plans to ship liquid CO2 from industrial sites fitted with carbon capture technology to an onshore terminal on the Norwegian west coast. From there, the liquified carbon will be transported by pipeline to a storage location under the North Sea, where it will be stored permanently.

“A rich oil- and gas-dependent country like Norway is to some extent obliged to develop such technology and make it more available to the rest of Europe. We have to do that. We have to pay that price,” Johansen says.

The €700m cost of the Oslo Varme incinerator carbon capture project would require EU funding of €300m, in addition to investments from the Norwegian government and the plant’s joint owners, the Oslo municipality and utility company Fortum. Beyond the cost, there are concerns over its climate credentials too.

Johansen says some of the scepticism derives from fears that carbon capture will make governments “more lazy when we come to recycling waste, reusing materials”. Others fear that relying on carbon capture technology – which typically traps 80-95% of emissions – will give a licence to maintain the world’s carbon-intensive status quo at the expense of pursuing cleaner alternatives.

Friends of the Earth Europe has called Norway’s carbon capture and storage plans “a spoke in the wheel of the energy transition” and warned that relying on the technology could delay a full-scale commitment to energy efficiency and renewables.

Johansen says both waste incineration and carbon capture will still be needed as “last resort” approaches to tackling pollution – even after rigorous efforts to opt for renewable and recycled materials while consuming less overall. The mayor claims that between 20% and 25% of Europe’s waste would be destined for landfill even after “quite advanced recycling”, where it would create far more carbon emissions than in an incineration plant.

For Johansen, the inevitable criticisms are dwarfed by the scale of the potential benefits in tackling the twin challenges of waste pollution and rising carbon emissions. It does not, he insists, mean that Norway can ignore the need for a more fundamental economic shift away from fossil fuels and towards sustainable growth.

“From a long-term perspective we must dismantle our own oil and gas industry,” he says. “It will take a lot of time because we are so dependent on the industry for labour. So many people work in the fossil fuel industry that it means many traditional working-class people are more and more sceptical about some of the green parties’ arguments because they feel they are taking away their jobs.”

The new industrial opportunities presented by carbon capture offer what the Johansen refers to as “normal jobs, for normal people”, which are within reach without the need for a university degree.

Johansen trained as a plumber before going into politics for Norway’s Labour party. “One of the most important things for me is to avoid the shift to green becoming a middle-class project,” he says. “We need to get all people on board, and they need to see that there is a prosperous future for them as well. It’s a new kind of industrialisation.”