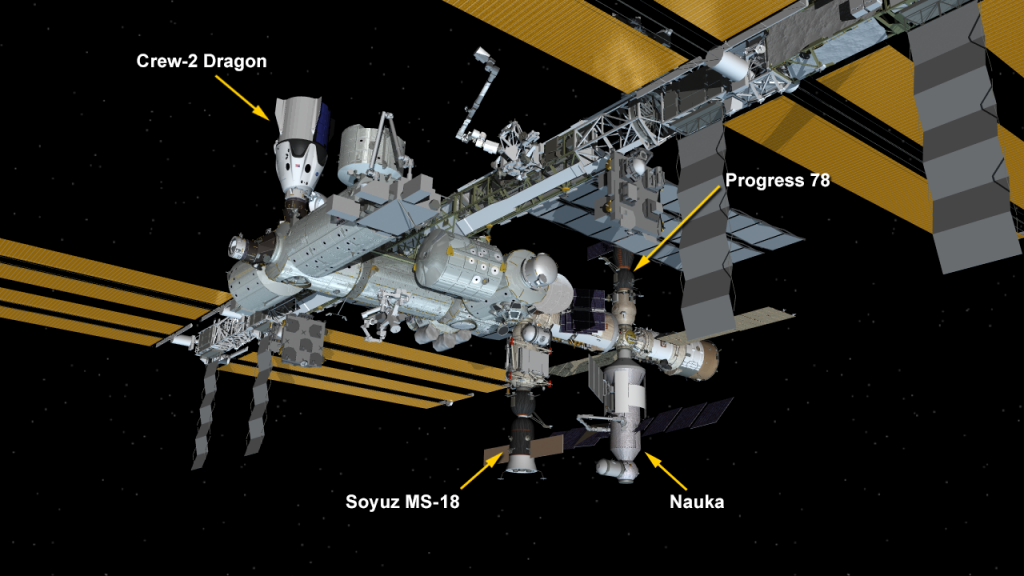

A Spanish tourist crosses a bridge over the Celeste river at Tenorio Volcano National Park in Upala March 18, 2008. The blue color of the lagoon, formed from chemical reactions of calcium carbonate and sulfur, is surrounded by an amazing rainforest that constitutes 12,819 hectares of this park. REUTERS/Juan Carlos Ulate (COSTA RICA)

Aug 4 (Reuters) - Costa Rican lawmakers this week will discuss a bill to permanently ban fossil fuel exploration and extraction, a move that would prevent future governments from pivoting on the issue as the popular eco-tourism destination country aims to decarbonize by 2050.

Costa Rica started efforts to ban fossil fuel exploration in 2002 under President Abel Pacheco. This ban was supposed to expire in 2014 but later extended until 2050. The new bill, backed by the administration of President Carlos Alvarado, would go further by permanently banning it.

"Our concern now is to remove the temptation, either today or at any time tomorrow, for there to be any current or future government who might think that returning to fossil fuels of the past century is actually a good idea for our country,” Christiana Figueres, a former U.N. climate chief and former Costa Rican government official who has publicly advocated for the bill, said in an interview with Reuters.

Only a few other countries have taken action to ban fossil fuel exploration and production, including France which aims to do so by 2040, and Belize, which prohibits exploration and drilling in all its territorial waters.

Costa Rica's rich biodiversity draws international tourists to its jungles and coastal eco-resorts, and it is considered a global model on climate change initiatives. It has never explored or extracted fossil fuels and gets 99% of its electricity from renewable sources, primarily hydropower, according to officials. The country of 5 million people aims to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

A permanent ban would "send a powerful message to the world," lawmaker Paola Vega told Reuters.

A pro-exploration movement has been trying since 2019 to garner support for a referendum on oil and gas exploration but has failed to bring about a vote. The bill for a permanent fossil fuel ban has faced opposition by some politicians who argue that the resources could help the Central American country bounce back from an 8.7% dip in GDP in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic.

Figueres, one of the architects of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, said fossil fuel extraction for economic recovery "makes absolutely no sense," as the Costa Rica's reserves have not been proven commercially viable.

"Were we to have them, we probably wouldn't see any income from them until at least 10 to 15 years from now, when the demand for oil and gas is actually going to be even less than it is now," Figueres said, adding she believes the ban has a good chance at approval.

"To have small countries actually take the lead is very important, because those of us that are actually doing the right thing, we definitely punch above our weight,” Figueres added. "Just because Costa Rica is tiny, it doesn't mean that we don't have a voice."

Lawmakers will hold discussions on the bill this week, though a vote may not come before October, according to a lawmaker involved.

Reporting by Cassandra Garrison; additional reporting by Alvaro Murillo in San Jose; Editing by David Gregorio