Global emissions must peak by 2025 to keep warming at 1.5°C: We need deeds not words

FOUR YEARS BEFORE CLIMATE EXTINCTION STARTS

IN EARNEST

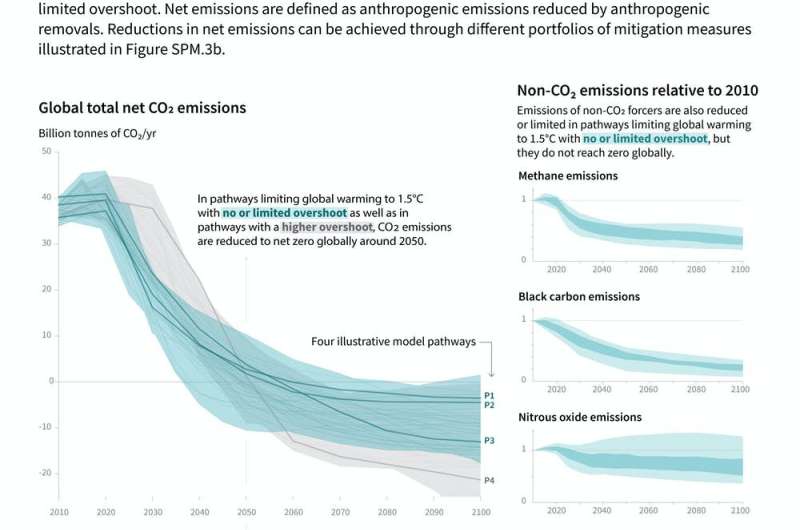

Earth could exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming—the "safe" limit for temperature rise outlined in the Paris Agreement—as soon as the early 2030s, according to a landmark report by the world's most senior climate scientists. Even in the most optimistic scenario, where the global community manages to significantly rein in greenhouse gas emissions, there is still only a 50:50 chance that global temperature rise will stop there.

The report's conclusion that staying below 2 degrees Celsius this century will only happen if emissions reach net zero by 2050 is well publicized. But there is one, rather more urgent addendum to that: global emissions must peak some time in the middle of this decade. In other words, within the next few years.

Let that sink in. It is a message which should concentrate the minds of every person on our planet. This is not "climate alarmism." It is, as far as experts can ascertain, fact.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, often referred to as the IPCC, is the international body behind the report. Established in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organisation and the United Nations Environment Programme, the IPCC provides governments at all levels with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies. It currently has 195 members and relies on thousands of scientists who volunteer their time to support its work.

After eight years of painstaking work, the panel's Working Group I report (WGI) has been published, providing a detailed assessment of the physical science underpinning past, present and future climate change. It is the definitive statement of the current levels of greenhouse gas emissions and their impact on the global climate, how they are changing, and how these figures relate to our targets for reducing them.

It will be followed in February 2022 by the WGII report, which will cover the impacts of climate change, adapting to them and how vulnerable different parts of the world are, and in March 2022 by the WGIII report outlining options for mitigating the climate crisis. Notably, it is a conservative assessment, and necessarily so because the IPCC goes to great lengths to avoid undermining the science by sounding false alarms. Which means, in IPCC terms, this is about as loud and urgent an alarm as we are likely to hear.

Extreme weather events

We can't say we weren't warned. In 2019 the IPCC published its Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5˚C. This gave us the UN's "12 years to save the planet" media soundbite—and the more urgent message that we had 18 months to decide how to do it.

The Paris Agreement commits us to limiting the average global temperature rise to 2˚C, which is based on accepting the impacts we think, with a high degree of confidence, that we can cope with. It also sets an aspirational target of 1.5˚C, which is considered the "safe" limit.

Neither limit means completely avoiding the impacts, but they minimize their disruption to our global society as we know it. Going beyond those limits increasingly risks sudden, highly disruptive and, over human timeframes, irreversible impacts.

However, recent extreme weather events such as the shocking flash floods in Germany and Belgium, the Canadian heatwave, the deluge that hit the Black Sea region and recent wildfires on the Greek island of Evia have led some scientists to conclude that what we are seeing now is "off the scale" in terms of what climate models have been predicting.

But the world has consistently failed to agree and enact concrete actions in response. This lack of action really matters because, as the IPCC report notes, any future temperature target is closely tied to the emissions up to that point. It is much easier to stop putting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it is to remove it, and the more we emit the more we degrade the ecosystems that naturally soak it up.

This urgency is leading climate scientists themselves to call for others in their field to speak out.

Deeds not words

With all eyes now turning to the COP 26 Glasgow climate summit, the Scottish "think and do" tank Common Weal has compiled a list of 21 for 21: the climate change actions Scotland needs now. Common Weal include a range of experts, many of whom, like the IPCC's scientists, contribute their time for free.

These actions largely detail the institutional changes needed in the energy sector. According to the IPCC, about 85% of CO₂ emissions come from burning fossil fuels. Naturally some are focused on Scotland, although these could be adopted elsewhere.

Drawing from more than six years of energy and climate change policy research by Common Weal, the Energy Poverty Research initiative, and the Built Environment Asset Management Centre at Glasgow Caledonian University, supported by members of other expert networks, and include:

- Introducing a law requiring the capture and recycling of waste heat

- Ending the use of coal and nuclear power

- Banning new oil and gas exploration, and divesting from fossil fuels

- Making grid-connection charges fair for all

- A legal right to work from home

- A legal right to a warm and energy-efficient home

20-minute neighborhoods, which provide all of people's need within a 20-minute walk, with links to sustainable transport and good cycling infrastructure.

Some people might worry about actions which ban or restrict the use of fossil fuels, but such is the urgency of the situation that, just like lockdowns during a pandemic, failing to taking action now will necessitate even more restrictive steps further down the line.

We need to remember that these actions will be offset by a better life for all of us—less poverty, better health, more jobs, stronger communities and better natural environments for us all to live in safely and enjoy.