Anatomy of an earthquake series

An international team led by scientists at GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, in collaboration with colleagues by Spanish, Italian and US institutions, is publishing a new scientific work on induced seismicity in Europe in the Journal Nature Communications.

The study focuses on the 2013 seismic sequence at the Castor platform of a former oil field, about 20 km offshore the coast of Valencia, Spain. During the initial phase of the development of a gas storage facility in the former oil field, thousands of earthquakes with magnitudes below 4.1 took place after the injection of gas into the depleted layers of the reservoir. While similar gas storage operations worldwide are typically not stimulating substantial seismicity, the Castor sequence remains to date the most significant case of seismicity related to this type of industrial operations in Europe.

The new study employs a combination of advanced seismological techniques applied to an enhanced waveform dataset to better understand the seismogenic process and the geometry of activated fault, which remained to date debated.

The new analysis identifies about 3,500 earthquakes, which took place at shallow depth between September and early October in the vicinity of the Castor injection platform. The study reveals for the first time three phases of the crisis. The first phase, accompanying gas injection from early to mid-September, was characterized by weak seismicity, progressively growing in magnitude. The injection stop marks the beginning of a second phase, which will last until end of September, where seismicity slowly migrated towards SW, driven by pore-pressure diffusion. The third phase, lasting until early October, saw a fast, backward migration, with the occurrence of all largest earthquakes as the failure of loaded asperities. Seismicity mostly affected a secondary fault, located close below the reservoir, and dipping opposite from the reservoir bounding fault.

The study demonstrates that a detailed view of the dynamics of seismic sequences can be resolved even in the lack of a dense local monitoring network, offering a benchmark for similar future studies elsewhere.

The insights are important also in the light that the Castor project has been abandoned after the occurrence of the earthquakes and the question of predictability of the risks and responsibility for such types of events are under public debate.Earthquakes continued after COVID-19-related oil and gas recovery shutdown

More information: Simone Cesca et al, Seismicity at the Castor gas reservoir driven by pore pressure diffusion and asperities loading, Nature Communications (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-24949-1

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres

Nathan Howes

Digital Reporter

Tuesday, August 10th 2021- The University of Utah seismograph stations recorded 1,008 earthquakes at Yellowstone Nationl Park in July, with the strongest tremor registering a 3.6 magnitude, says the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

July was fairly active seismically for Yellowstone National Park, which recorded a figure not seen since June 2017, according to a recent report from the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

The University of Utah seismograph stations recorded 1,008 tremors, but all of them registered as minor magnitudes. The strongest earthquake had a 3.6 magnitude, occurring at a depth of 17.7 km beneath Yellowstone Lake.

SEE ALSO: Yellowstone's Old Faithful geyser might stop erupting, here's why

"This number is preliminary and will likely increase, since dozens more small earthquakes from July 16 require further analysis. This is the most earthquakes in a month since June 2017, when [more than] 1,100 earthquakes were located," the USGS said.

A swarm of 764 earthquakes occurred beneath Yellowstone Lake, beginning on July 16. The pack consisted of four earthquakes in the magnitude 3 range and 85 in the magnitude 2 range.

IS AN ERUPTION FORTHCOMING?

Yellowstone is adored for its picturesque scenery and known for its distinctive geothermal features, such as Old Faithful and its caldera complex. The latter is referred to by many as a supervolcano.

With the high number of earthquakes last month, does the tally indicate an imminent eruption at Yellowstone? Rest assured, the answer is no. The USGS says this level of seismicity is not unprecedented and it doesn’t reflect magmatic activity, as no other indicators were found.

"Earthquakes at Yellowstone are dominantly caused by motion on pre-existing faults and can be stimulated by increases in pore pressure due to groundwater recharge from snow melt. If magmatic activity were the cause of the quakes, we would expect to see other indicators, like changes in deformation style or thermal/gas emissions, but no such variations were detected," USGS said in the report.

The Yellowstone area experiences anywhere from 700 to 3,000 earthquakes every year, according to the National Park Service.

Although most are too small to be felt, the quakes are an indication of the state of the Yellowstone region -- one of the most seismically active areas in the United States. Each year, multiple tremors registering with magnitudes 3 or 4 are felt by people within the park.

THE CHANCES OF ANOTHER MASSIVE ERUPTION

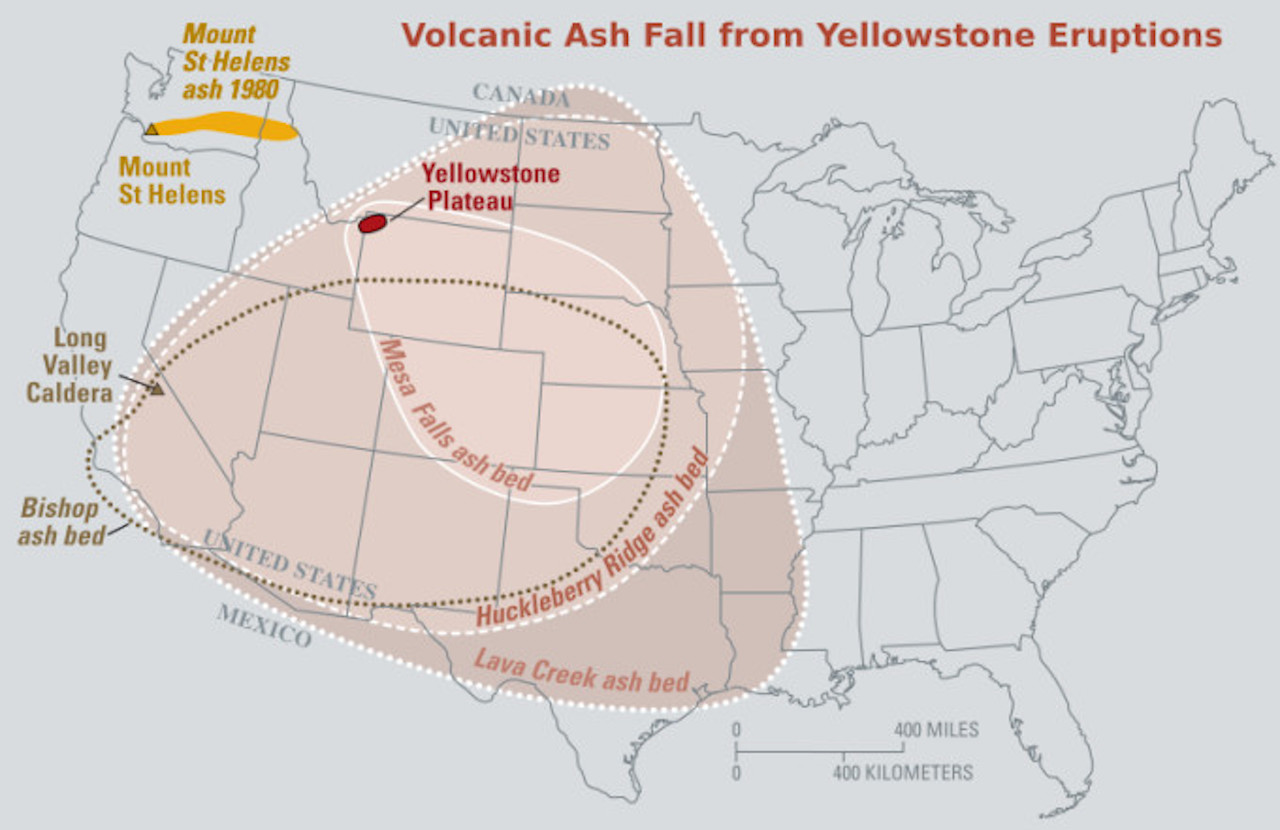

Yellowstone has produced three extremely large volcanic eruptions (caldera-forming eruptions) in the past 2.1 million years, according to the USGS. In each cataclysmic event, large volumes of magma exploded at the surface and were sent into the atmosphere as mixtures of red-hot pumice, volcanic ash, and gas that disperse as pyroclastic flows in all directions.

Data from the agency suggests that the Yellowstone caldera system erupts approximately every 730,000 years, with the most recent explosion occurring 640,000 years ago.

The last eruption created a 56-kilometre-wide, 80-kilometre-long Yellowstone caldera. Pyroclastic flows from the discharge left thick volcanic deposits known as the Lava Creek Tuff, which comprises the north wall of the caldera. Vast volumes of volcanic ash skyrocketed into the atmosphere, and some of it can still be found in places as far from Yellowstone as Iowa, Louisiana and California.

If another catastrophic eruption from Yellowstone were to happen, the effects would be worldwide, the USGS says. Thick ash deposits would bury extensive areas of the United States, and huge volumes of volcanic gases would be shot into the atmosphere. It would likely affect the global climate and have "enormous effects on human activity, especially agricultural production, for many years."

"Fortunately, the Yellowstone volcanic system shows no signs that it is headed toward such an eruption. The probability of a large caldera-forming eruption within the next few thousand years is exceedingly low," the USGS said.

It added that a more likely scenario to occur is the eruption of a lava flow, which would be "far less" devastating than a large explosive, caldera-forming blast.

VIDEO: SUPERVOLCANO COULD ERUPT CAUSING ASH TO FALL OVER THE ENTIRE GLOBE

Thumbnail courtesy of Videoblocks.

With files from Isabella O'Malley.

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.

The answer is: Probably not.

By Brandon Specktor - Senior Writer

The Earth is rumbling beneath Yellowstone National Park again, with swarms of more than 1,000 earthquakes recorded in the region in July 2021, according to a new U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) report. This is the most seismic activity the park has seen in a single month since June 2017, when a swarm of more than 1,100 rattled the area, the report said.

Fortunately, these earthquakes were minor ones, with only four temblors measuring in the magnitude-3 range (strong enough to be felt, but unlikely to cause any damage) — and none of the quakes signal that the supervolcano underneath the park is likely to blow, park seismologists said.

"While above average, this level of seismicity is not unprecedented, and it does not reflect magmatic activity," according to the USGS report. "If magmatic activity were the cause of the quakes, we would expect to see other indicators, like changes in deformation style or thermal/gas emissions, but no such variations were detected."

Related: Rainbow Basin: Photos of Yellowstone's colorful grand prismatic hot spring

Throughout July 2021, the University of Utah Seismograph Stations, which are responsible for monitoring and analyzing quakes in the Yellowstone park region, recorded a total of 1,008 earthquakes in the area. These quakes came in a series of seven swarms, with the most energetic event occurring on July 16. According to the USGS, at least 764 quakes rattled the ground deep below Yellowstone Lake that day, including a magnitude-3.6 earthquake — the single largest of the month.

The month's remaining six swarms were all smaller, including between 12 and 40 earthquakes apiece, all measuring below magnitude 3, the report said.

These quakes are nothing to worry about, the USGS added, noting that the earth-shaking is likely the result of motion on preexisting faults below the park. Fault movements can be stimulated by melting snow, which increases the amount of groundwater seeping under the park and increases pressure levels underground, the researchers said.

Yellowstone is one of the most seismically active regions in the U.S.; the area is typically hit by anywhere from 700 to 3,000 earthquakes a year, most of which are imperceptible to visitors, according to the National Park Service. The biggest quake on record in Yellowstone was the magnitude-7.3 Hebgen Lake quake, in 1959.

Why so shaky? The park sits atop a network of fault lines associated with an enormous volcano buried deep beneath the ground (this volcano last erupted about 70,000 years ago, according to the USGS). Earthquakes occur as the region's fault lines stretch apart, and as magma, water and gas move beneath the surface. These features also feed the park's reliable geysers and steamy hot springs.

The Yellowstone volcano has erupted several times in the past, with gargantuan eruptions occurring every 725,000 years or so. If this schedule is accurate, the park is due for another big eruption in about 100,000 years. Such an eruption would devastate the entire United States, clogging rivers with ash across the continent and causing widespread drought and famine, Live Science previously reported.

RELATED CONTENT

—Yellowstone National Park: The early years (photos)

—In Photos: Best national parks to visit during winter

—Yellowstone's grizzly bear trapping photos

Originally published on Live Science.