By Alex BoydCalgary Bureau

Sun., Aug. 15, 2021

Corb Lund is not enjoying this interview.

The lanky Juno-winning musician, known for his playful lyrical takes on rural life on the Prairies, is calling while on his way home to southern Alberta after a stint in studio in Edmonton working on some new music. But he hasn’t phoned to talk about his latest project, or even the one before it, an album released to critical acclaim in the middle of a pandemic.

Instead, he’s stolen time from his primary gig to talk about a side project that has recently rebranded him as an emerging, albeit reluctant, advocate: stopping a controversial plan to open up the Rocky Mountains to coal mining.

“I would rather be playing music, frankly,” says Lund, sounding exasperated.

“I blame the government. I don’t even blame the coal companies, because coal companies are going to coal-company, right? That’s what they do. It’s the government allowing them to do it.”

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/08/15/how-his-plan-to-open-the-canadian-rockies-to-coal-mining-set-albertas-jason-kenney-against-country-music-stars/_1_corb_lund.jpg)

Last spring, the Alberta government set off a firestorm with the quiet removal of a 44-year-old policy preventing most open pit coal mining in the iconic mountain range. At a time when pandemic polarization seems to have split Albertans into warring camps on just about everything, coal mining might be one of the few areas of common ground.

In short, most people are mad.

The provincial government maintains that a new plan is required because the old coal policy was “largely made obsolete through more modern oversight,” Jennifer Henshaw, press secretary to Energy Minister Sonya Savage, said in an email. The old one doesn’t even mention climate change, she points out.

The mines would also bring in revenue at a time when the province is struggling to recover from the double whammy of the pandemic and plummeting oil revenue — in 2017, the Alberta government collected $15.7 million from coal production on publicly owned land.

But the anger is such that the current government, which flaunts big trucks and cowboy hats with an enthusiasm that’s notable, even for Albertan politicians — Premier Jason Kenney is preparing for a tour of the province in his signature blue pickup truck — is facing pushback from what might seem like an unexpected source: country music stars.

Alberta’s conservative history can tempt outsiders to paint the whole province with the same political brush, an impression reinforced by the current government, which has embraced the rural parts of the province as its base.

But its coal plans have united environmentalists, many conservatives and several First Nations as well as big country names, exposing the many shades of grey in terms of how Albertans think of political allegiance, resource development and even the future of their province.

“I know that some of the current politicians tried to frame this as a bunch of urban busybodies but honestly, I know more rural people against it,” Lund says.

“It’s a very wide coalition of people.”

A rising chorus

Over the past six months, a movement of sorts has coalesced around Lund, who, in addition to speaking out in interviews and online, has hosted a horse ride and a protest concert in the sprawling ranch country located in the mountain foothills south of Banff National Park. He’s even publicly mused about attempting a referendum under new government legislation that allows private citizens to put issues to the ballot.

One by one, other members of Canadian country royalty have joined the chorus.

Paul Brandt, whose hit songs include “Alberta Bound,” once used as a soundtrack for Ford commercials, tweeted that “Corb Lund is right,” alongside photos of him fishing in a gleaming stream. Terri Clark tweeted that the Canadian Rockies are “part of my soul” and linked to Lund’s Facebook page.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/08/15/how-his-plan-to-open-the-canadian-rockies-to-coal-mining-set-albertas-jason-kenney-against-country-music-stars/paul_brandt.jpg)

In a video posted online, Terry Grant, otherwise known as “Mantracker,” from the show of the same name in which he used tracking skills and a horse to hunt down contestants, came out strongly against the mine. “I grew up down there, chasing cows and cowboying, guiding and hunting. It’s amazing country.”

Of course, there will always be critics who argue that entertainers should stay out of politics.

Corb Lund is usually one of those critics.

“I don’t normally speak about stuff like this,” he says. “A lot of times when people in positions of notoriety or celebrity or whatever speak out about stuff, they don’t really know what they’re talking about. They’re kind of stupid, and I didn’t want to be that guy.”

To that end, in the past few months, he’s taken on a crash course in coal, speaking to politicians, coal lobbies, scientists and conservationists.

The Rockies are iconic to Albertans, and the opposition is built on concerns that mines will open up vast pits to extract the coal beneath, and at the same time pollute the water, harm wildlife and knit access roads and rail lines across land that is in many ways undisturbed.

Before a long weekend in May

The furor began over a year ago, with an email sent to media on the Friday afternoon before the May long weekend. In it, the government announced it was replacing the “outdated” 44-year-old coal policy that had prohibited much mining in the Rockies.

Instead, the government was bringing in what it called “modern regulatory processes, integrated planning and land use policies.” While the government said sensitive land in the eastern slopes, for example, would continue to be protected, coal companies would be able to apply to develop new projects.

“Government is placing a strong focus on creating the necessary conditions for the growth of export coal production,” the release read.

The reaction was swift.

The Alberta Wilderness Association pointed out the move had the potential to open up more than 4.7 million hectares of environmentally sensitive lands to coal exploration. A group of ranchers whose grazing leases were suddenly eligible for mining, and the Ermineskin and Whitefish Lake First Nations moved ahead with legal action, arguing the changes had been made without required consultation.

In January, the government said it had “listened carefully” and announced it was cancelling 11 coal leases and would pause any future lease sales. The old policy was eventually reinstated while a five-member panel was tasked with consulting with Albertans about a new way forward. Suggesting how widely the issue resonated, a preliminary survey done by the panel found the majority of Albertans felt the development of coal affected them.

Meanwhile, the federal government has waded into the fray, armed with the argument that issues of climate change and pollution are national matters.

Federal Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson announced in June that Ottawa would conduct an environmental review of any new coal project that could potentially release selenium, a mineral found in Alberta’s coal beds that is toxic to fish.

Last week, Ottawa rejected the Grassy Mountain proposal, one of the most high-profile projects, after a joint review panel concluded it would have major environmental effects.

But the real litmus test will come this fall, when the Alberta government goes back to the drawing board on a new coal policy.

Alberta premiers — then and now

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/08/15/how-his-plan-to-open-the-canadian-rockies-to-coal-mining-set-albertas-jason-kenney-against-country-music-stars/jason_kenney_2021_stampede.jpg)

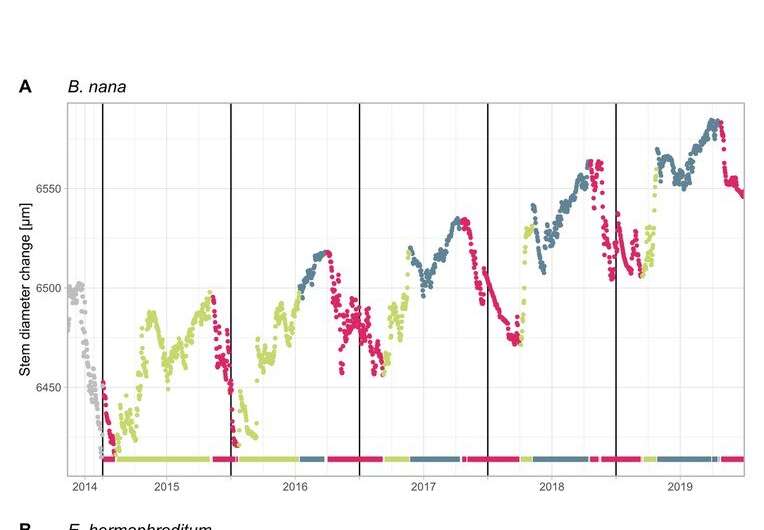

Most of the coal currently being eyed by commercial interests in Alberta lies within a 20-kilometre-wide band of rolling foothills that runs along the eastern edge of the Rockies south of Banff National Park.

Falling roughly between a winding secondary highway known as the Cowboy Trail — a nod to decades of local ranching history — and the Rockies proper, the eastern slopes are considered one of the last patches of the true Prairie ecosystem that once blanketed much of the continent.

It’s important habitat for grizzly bears and threatened species such as westslope cutthroat trout; and the water that flows through here feeds much of the southern half of the province — including the city of Calgary.

Coal mining is not unheard of in this part of the world. To the south, the Crowsnest Pass, one of the few passable routes between Alberta and British Columbia, is still shot through with old mine shafts. But the use of coal for energy waned in the 1960s and then, in 1976, Alberta brought in a coal policy that put management of water first and restricted much new coal development.

At the time, David Luff was a brand new government employee who had been hired the year before to help implement the coal policy and develop a plan for the eastern slopes.

The premier of the day, Peter Lougheed, still casts a long shadow in Alberta politics. Luff says he believes Lougheed, through the coal policy, was implementing a long-term vision of stability and prosperity for the province that Luff argues was ahead of its time.

“In 1976, people didn’t talk about climate change, they weren’t worried about drought. They weren’t worried about the forest fires that we now see on a yearly basis,” he says. “None of that was really on anyone’s radar.”

The policy protected much of the land and encouraged coal companies, which had to get special permission for most open-pit mines in Alberta, to move to B.C., where mines have released so much selenium it’s now ending up in Montana.

Since the removal of the Lougheed-era policy, Luff says companies have already begun to explore future mine sites, building roads and sinking core holes into the rock to probe for coal.

“With the rescinding of the policy, the government was stating water is no longer important. Water is not the highest priority; coal development is the highest priority. And Albertans found that to be fundamentally wrong,” Luff says.

A different kind of coal

Coal is one of the emerging villains of the fight against climate change, and Canada has committed to phasing out coal-fired electricity by 2030. Alberta is currently on track to accomplish that even earlier and hopes to transition off by 2023, officials say.

But a complicating factor here is there are different types of coal. Much of what the Alberta government is looking to produce is what’s called metallurgical coal. With more carbon and less ash and moisture than regular coal, also known as thermal coal, metallurgical coal is used to make steel and even Canada says it can’t be phased out just yet.

According to the provincial website, Alberta still produces about 25 million to 30 million tonnes of coal every year from its remaining nine mines — two of which produce metallurgical coal, and the remaining seven of which are devoted to thermal, much of which is sold to other countries.

But the federal environment minister says that while the first priority is eliminating thermal coal, eventually the same thing will happen to metallurgical.

“There are a number of different processes and technologies that people are looking to deploy that will help us to reduce those emissions and move us away from metallurgical coal,” Wilkinson said, pointing to a couple of Canadian companies that are trying out electric furnaces to make steel.

Luff, for his part, is not anti-industry. He would go on to become an assistant deputy minister in the energy department, then become a vice-president for the Canadian Association for Petroleum Producers before creating his own consultancy company, but he worries that government is putting profit ahead of the long-term interests of Albertans.

He worries Alberta’s politicians aren’t playing the long game here, which he argues shows industry switching away from coal, even for steel production. The potential risk to the province’s drinking water and an iconic part of the province won’t be done away with so easily.

“Maybe it’s just a lack of understanding that, yes, Alberta is a province that benefits from the development of its resources, whether it’s oil and gas, or timber development and so on. But Albertans also recreate, and spend a great deal of time in the mountains, in northern Alberta in the boreal forest — hiking, canoeing, fishing, hunting — and many Canadians, I don’t think, are aware of that,” he says.

“Albertans do look to find a balance between the development of resources, but also ensuring that the environment and social values will be maintained in perpetuity.”

‘I don’t know what he’s thinking’

Two and a half years into its maiden term — a significant chunk of which involved navigating a global pandemic — Jason Kenney’s United Conservative government is no stranger to controversy.

There was the time at least seven MLAs and senior government officials were caught travelling for the holidays despite official advice, or the time Kenney himself was photographed having drinks on the balcony of the so-called Sky Palace — a government office that a former premier tried to turn into a luxury apartment that is now Albertan shorthand for government arrogance — with a group of ministers, including the health minister, while flouting pandemic rules.

There is growing evidence Albertans are getting fed up. While many leaders have enjoyed pandemic bumps to their approval ratings, Kenney has the lowest level of support of a premier in the country.

According to an Angus Reid poll from June, his approval was sitting around 31 per cent, or about half of where it was when he swept to victory two years ago.

But while much of the pushback against Kenney’s government has tended to splinter along political lines — his rule-resistant COVID-19 response seemed designed to appease a rural base, experts say — the fury of coal stands out for its cross-partisan appeal.

When he was running to be leader of the newly minted United Conservative party four years ago, Kenney stood in front of a green and white sign emblazoned with his signature and what he called the Grassroots Guarantee — a promise that policy would be developed by membership and not by leadership alone.

It was an attempt to throw off the shackles of conservative arrogance in the province, and yet it’s been a challenging promise to deliver on, says Lori Williams, a political scientist at Calgary’s Mount Royal University.

A small poll in February found that almost seven in 10 Albertans surveyed were against development of formerly protected areas and half strongly opposed getting rid of the coal policy specifically and yet the government has plunged ahead with changes. Some government MLAs have spoken of an inability to get Kenney’s ear.

“The inability to respond to the concerns that are being raised by his base is a bit surprising,” Williams says.

Kenney came to power by combining the province’s two Conservative parties, and as his popularity drops, it’s a partnership that risks unravelling. He’s struggled to keep the right wing of the party intact, which some have speculated explains why he’s pushed ahead with the development often favoured by the right.

“I don’t know what he’s thinking,” Williams says. “I often wonder if he knows the Alberta that he is now governing; it’s not the Alberta that he left in the 1990s. But sometimes he governs as if it is that Alberta.”

‘This is just about me not wanting the Rockies ruined’

Lund, who says he agrees with some ideas on the right and some on the left, says this isn’t about politics.

“I don’t like any political parties. I don’t like groups of people in general. I don’t trust them. I only trust individuals. So this is just about me not wanting the Rockies ruined for everyone,” he says. “And turns out that’s resonated across political lines.”

Fellow musician Brett Kissel was raised on a ranch north of Edmonton but grew up on country music stages — he recorded his first album at age 12 and has since had four singles hit No. 1 on Canadian country music charts. After watching one of Lund’s videos about coal this spring, he immediately called him to ask how he could help, he says.

He agrees this is not about politics. He’s made public appearances with Kenney and says there are a number of things the current government has done well since the pandemic began.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/08/15/how-his-plan-to-open-the-canadian-rockies-to-coal-mining-set-albertas-jason-kenney-against-country-music-stars/brett_kissel.jpg)

Personal relationships aside, he says, he’s decided to speak out because of what he considers a “bad deal” for Alberta. As he sees it, the government has backed itself into a corner — if it backs down now, it will invite environmentalists to fight back on other causes. But he argues that the time has come for the province to heed the voices of the province.

Speaking a few hours before stepping onto the stage in Quebec for one of his first post-pandemic appearances this month, he said it’s a comment on Alberta politics when even the “true blue Albertans” are starting to push back.

“We’re pro oil. We’re pro industry. We’re pro money. We’re pro generational wealth. So even us, we’re the ones who are like, ‘Yeah, no, this is too far,’” Kissel says.

He says he feels for the people who work in coal who were looking forward to new opportunities — only to have those new mines threated by the pushback. The musicians who have spoken out have all received significant heat for that reason, he says.

Still, he calls the mine proposals a “bad deal” for the province, with the promise of a few hundred local jobs and “miniscule” royalties.

“It’s very difficult when we are talking about other people’s livelihoods,” he says. “But you know what, the pros for this situation do not outweigh the cons that are going to be for the rest of the province.”

Right now, the government is awaiting the coal policy committee’s report, which is due by Nov. 15. Although “we cannot speculate on the content or details of a modernized provincial coal policy,” the report will “inform” the new plan, the Alberta energy minister’s press secretary said in an email.

A clearer timeline for a new policy is expected this fall.

Lund and others will be watching.

“I feel like the wind is in our sails, but I think we need to keep pushing until we have a new policy in place that clearly sorts this out so that we don’t have to deal with it again, five years from now,” he says.

“In this divided time, it’s been refreshing to see that we can all agree on clean water at least, right?”

Alex Boyd is a Calgary-based reporter for the Star.