Do you want to design a perfect robot? Study squirrels

By lucia f. Jacob Nathaniel Hunt and Robert J.

Tree squirrels are the Olympic divers of the rodent world, leaping gracefully between branches and structures high above the ground. And as with human divers, a squirrel’s success in this competition requires both physical strength and mental adaptability.

Jacobs’ lab studies cognition in wild fox squirrels on the Berkeley campus. Two species: the eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and the fox squirrel (black squirrel) – thrive in campus landscapes and are willing participants in our behavioral experiments. They are also masters at two-dimensional and three-dimensional spatial orientation, using sensory cues to move through space.

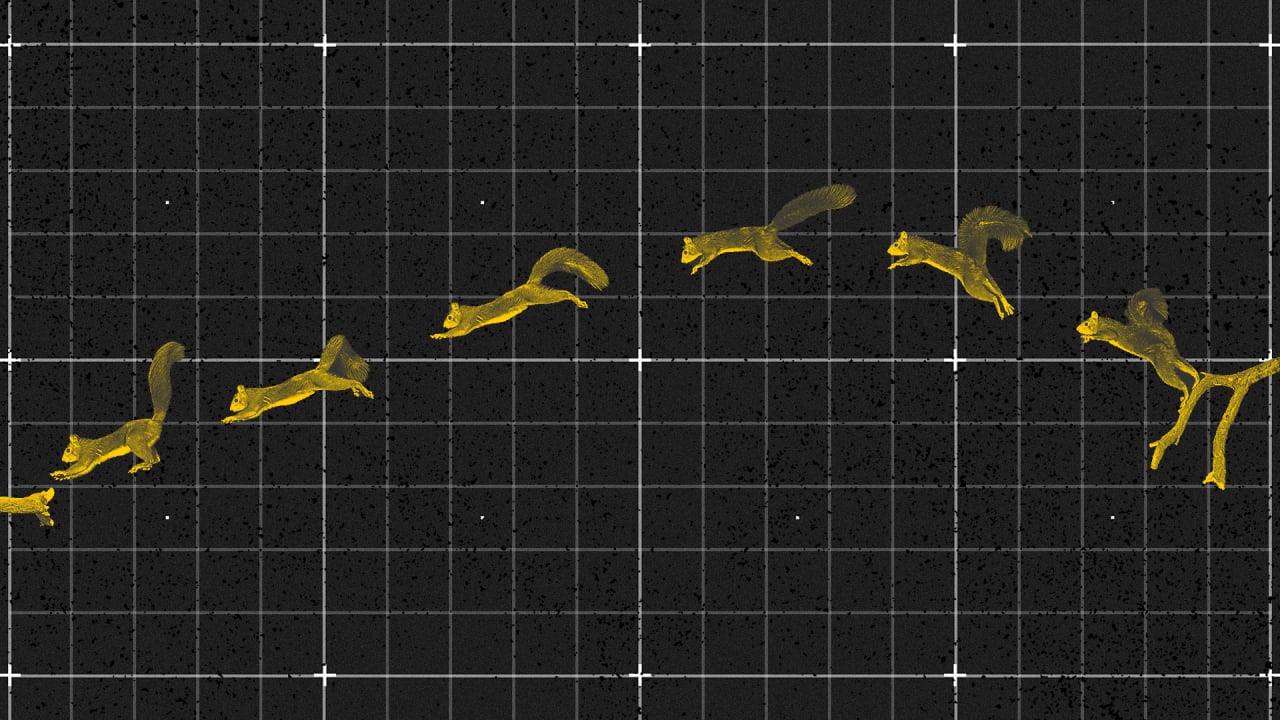

In a recently published study, we showed that squirrels jump and land without falling by making trade-offs between the distance they have to cover and the elasticity of their take-off position. This research provides new insights into the roles of decision-making, learning, and behavior in challenging environments that we are sharing with human movement researchers and engineers. Currently, there is no robot as agile as a squirrel, and none that can learn or make decisions about dynamic tasks in complex environments, but our research suggests the kinds of skills these robots would need.

Thinking on the go

While the life of a squirrel may seem simple to human observers (climb, eat, sleep, repeat), it involves finely honed cognitive abilities. Squirrels are specialized seed dispersers: They harvest their winter supply of nuts and acorns over a six to eight week period in the fall, burying each nut separately, and relying on spatial memory to retrieve them, sometimes months later.

Going through the air

Our new study brought together squirrel psychologists and comparative biomechanists to ask whether squirrel cognitive decision-making extends to dynamic changes in locomotion – the famous squirrel leap. How do the squirrels’ perceived capabilities of their bodies and their assumptions about the stability of the environment shape their decisions about movement?

Robert Full of the PolyPEDAL Laboratory is recognized for his studies that extract fundamental design principles through experiments on locomotion in species with unique specializations for movement, from crabs to cockroaches to jumping lizards. Graduate students Nathaniel Hunt, who is trained in biomechanics, and Judy Jinn, who is trained in animal cognition, took on the challenge of evaluating how a jumping squirrel might respond to sudden changes in the location and flexibility of experimental branches.

To study this question in wild squirrels, we designed a magnetic climbing wall that could be ridden on wheels and rolled to Berkeley’s famous eucalyptus forest to meet squirrels on their own lawn. We brought high speed cameras and peanuts to persuade the squirrels to wait patiently for their turn on the wall.

Our goal was to persuade the squirrels to take off from a flexible trampoline attached to the climbing wall and onto a fixed perch protruding from the wall that contained a bounty of shelled walnut. And once again, the squirrels surprised us with their stunts and innovation.

By increasing the springboard’s elasticity and the distance between it and the goal, we could simulate the challenge a squirrel faces as it runs through tree branches that vary in size, shape, and flexibility. Squirrels jumping through a gap must decide where to take off based on a trade-off between the flexibility of the branch and the size of the gap.

We found that squirrels ran farther along a stiff branch, so they had a shorter, easier jump. Rather, they took off with just a few steps of flexible branches, risking a longer leap.

Using three branches that differ in flexibility, we guess the position of your take-off assuming the same risk of jumping from an unstable branch and jump distance. We were wrong: our model showed that squirrels cared six times more for a stable take-off position than the distance they had to jump.

The squirrels then jumped off a very rigid platform. Unbeknownst to the squirrels, we replaced an identical-looking platform that was three times more flexible. From our high-speed video, we calculated how far the center of the squirrel’s body was from the landing perch. This allowed us to determine the landing error – how far the center of the squirrel’s body landed from the goal position. The squirrels quickly learned to jump off the very flexible branch which they expected to be rigid and could catch the landing in just five attempts.

When we raised the ante even higher by raising the height and increasing the distance to the goal perch, the squirrels surprised us. They instantly adopted a novel solution: parkour, literally bouncing off the climbing wall to adjust their speed for a graceful landing. Once again, we discovered the remarkable agility that allows squirrels to evade predators in one of the most challenging environments in nature, the canopy of trees

Millions of people have seen squirrels solve and raid “squirrel-proof” bird feeders, either live in your backyard or in viral documentaries and videos. Like Olympic divers, squirrels must be flexible both physically and cognitively to be successful, making quick bug fixes on the fly and innovating new movements.

With the funding this project attracted, we have teamed up with a team of roboticists, neuroscientists, materials scientists, and mathematicians to extract design principles for squirrel jumps and landings. Our team is even looking for information on brain function by studying jump planning in laboratory rats.

Our analysis of the remarkable feats of squirrels can help us understand how to help humans who have walking or grasping impairments. Additionally, with our interdisciplinary team of biologists and engineers, we are trying to create new materials for the smartest and most agile robot ever built, one that can aid search and rescue efforts and quickly detect catastrophic environmental hazards such as toxic chemicals. releases.