Last weekend’s earthquake was a catastrophe. But for the country’s political class, it came at exactly the right time.

By Jonathan M. Katz, the author of the upcoming Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire.

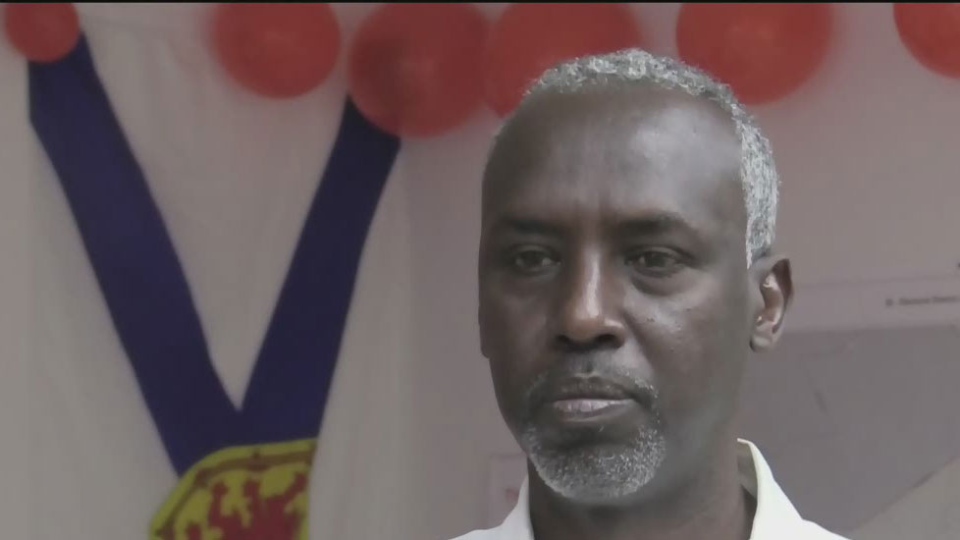

A soldier stands over debris during rescue efforts after a 7.2-magnitude earthquake struck Haiti and Tropical Storm Grace moves over Jamaica in Les Cayes, Haiti, on Aug. 17. RICHARD PIERRIN/GETTY IMAGES

AUGUST 18, 2021,

The difference between Saturday’s deadly earthquake in Haiti and the far more catastrophic one 11 years ago was about 50 miles. The 2010 earthquake’s epicenter was close to Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital and home to roughly a third of the country’s nearly 10 million people at the time. The 2021 temblor was farther along Haiti’s rural southern peninsula, near the town of Petit-Trou-de-Nippes. Despite releasing nearly twice as much energy than the earlier earthquake, it affected far fewer people in smaller cities like Les Cayes and Jérémie and even smaller surrounding villages and towns. This was still very bad for people in those places but a lucky break for those living in the capital. Earthquakes, like much in life, depend on where you stand.

For officials of Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry’s so-called caretaker government, the earthquake may have seemed like a particularly lucky break, not only because they and their homes were largely spared. The powerful shock offered a disruption—and perhaps a not-unwelcome distraction—from a political crisis that was threatening to spiral out of their control.

Henry, a 71-year-old neurosurgeon, had been nominated for the number-two job by then-Haitian President Jovenel Moïse just over a month ago on July 5. Two days later, Moïse was gunned down in his home. The assassination set off a frantic search for the perpetrators as well as a scramble for political power. In Haiti, that power doesn’t always mean much: Its leaders have long been made to answer to external forces, especially the United States, or risk being overthrown. Henry was made the country’s de facto leader on July 20—not by any Haitian democratic process but under pressure from a press release by the so-called Core Group: a consortium of ambassadors from the United States, France, Canada, Germany, Brazil, Spain, the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and the European Union, who, in the absence of a president or functioning parliament (and sometimes with them in place), call the shots.

None of this had been going particularly well in the weeks between the assassination and earthquake. Henry is still surrounded by, and was himself a part of, the same coterie of officials who served the late president—who came into office in a fraudulent, super low participation election five years before and whose popularity only plummeted from there. They served at the pleasure of the equally unpalatable, extremely tiny Haitian business elite, whose stranglehold on the country’s import-dependent economy gives them far more power than the nominal government.

Moïse’s position, and all of theirs, also relied on the third vertex of the triangle: the armed street gangs whose role in silencing critics and defending the government has become so blatant that major gang leader Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier openly led a rally of more than 1,000 mourners in the capital, where he vowed vengeance on behalf of his slain ally, Moïse, in late July. The precariousness of the government’s position and the exhausted and angry Haitian masses are likely why almost immediately following the assassination, the governing clique asked for a U.S. military intervention on its behalf. (U.S. President Joe Biden and U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, busy with the now-unraveling withdrawal from Afghanistan, demurred.)

The investigation into Moïse’s assassination was also in shambles when the earthquake struck. Despite having quickly rounded up more than 40 suspects—including 18 Colombian mercenaries allegedly skilled enough to evade bodyguards and carry out Haiti’s first presidential assassination in over a century yet unprofessional enough to get almost immediately captured or killed—no one has yet been taken to court. Meanwhile, as the Washington Post reported on Aug. 8, some judges and clerks investigating the assassination have gone into hiding, “fearing for their lives and claiming they faced pressure to tamper with reports.” The farrago of investigation, cover-up, and revenge raised the immediate specter of a political operation aimed not primarily at finding perpetrators but eliminating would-be rivals.

The new earthquake may put an end to all of that. Political jockeying in the retraumatized capital will likely die down. Foreign powers’ appetite for a politically delicate—perhaps personally embarrassing—investigation into Moïse’s assassination can now likely be delayed even further if not completely swept under the rug. All eyes still on Haiti are now on the mostly rural quake zone, where the injured are in dire need of care and bodies are still being pulled out of the rubble.

Hampering—and thus prolonging—the crisis response is the affected areas’ remoteness from the capital, which is also the location of the nearest major airport. Few roads go in and out, and some of those that do were damaged by the earthquake or blocked by landslides provoked by the endless string of aftershocks. Making matters more delicate, the only road out of Port-au-Prince to the southern peninsula goes through Martissant, an impoverished area controlled by gangs. That means any materials or people meant to be transported to or from Port-au-Prince will have to be transported in coordination with, or at least with permission from, the gangs and their sponsors.

The earthquake victims, not to mention the rest of the Haitian majority, are left basically on their own. Haitian communities have an incredible capacity for self-reliance—one forged out of necessity in the face of repeated abandonment. Hospitals and civil protection officials are ill equipped. The so-called government can do little. Because Moïse refused to hold a single election, at any level, during his presidency, there are only 10 elected officials left in the entire country—all of them senators. (He simply appointed mayors to oversee districts like Les Cayes.) There is little accountability to Haiti’s citizens and few formal mechanisms left to ask for help.

That may occasion a renewed request for U.S.—and specifically U.S. military—involvement from the caretaker government. (I reached out to a few Haitian officials to see if such a renewed request was planned; the individual who got back to me said he did not know.) Biden has put U.S. Agency for International Development Administrator Samantha Power in charge of the Haiti operation. She tweeted on Saturday night that she had spoken to the head of U.S. Southern Command, Adm. Craig Faller, “about the impact of today’s earthquake in #Haiti and how the @DeptofDefense could support @USAID’s response.” Perhaps the hoped-for U.S. military intervention could be in the offing after all.

READ MORE

Haiti’s Foreign Language Stranglehold

Around 90 percent of Haitians speak only Haitian Creole. So why is school mostly conducted in French? ARGUMENT | BENJAMIN HEBBLETHWAITE

Or perhaps things could go in an entirely different direction. With the death toll from the southwestern quake still horrific but apparently much lower than its predecessor (the latest count stood at 1,941 deaths), and foreign officials and media preoccupied with Afghanistan’s collapse, the prospects of a massive response in Haiti seem slim. So does the prospect of another flood of donations from the U.S. public on the scale of 11 years ago. But given the terrible results of that response, and the fact that only a tiny fraction of the money raised after the 2010 quake ever reached survivors or Haitian organizations, little will be lost if the same experience isn’t repeated now. Perhaps the relatively smaller, relatively more remote disaster will give space for local and Haitian-run organizations to take charge, and even create an opening for a new politics from below. On Tuesday, Barack Obama—who as president oversaw the top-heavy 2010 response and the manipulation of the ensuing Haitian presidential election—tweeted out a list of mostly local and locally-run organizations for his followers to donate to. It isn’t much, but it’s a start.

Jonathan M. Katz is a journalist. He is the author of The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. His next book, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire, will be published in January by St. Martin’s Press. His newsletter, The Long Version, can be found at katz.substack.com. Twitter: @KatzOnEarth