Lucas Matney@lucasmtny

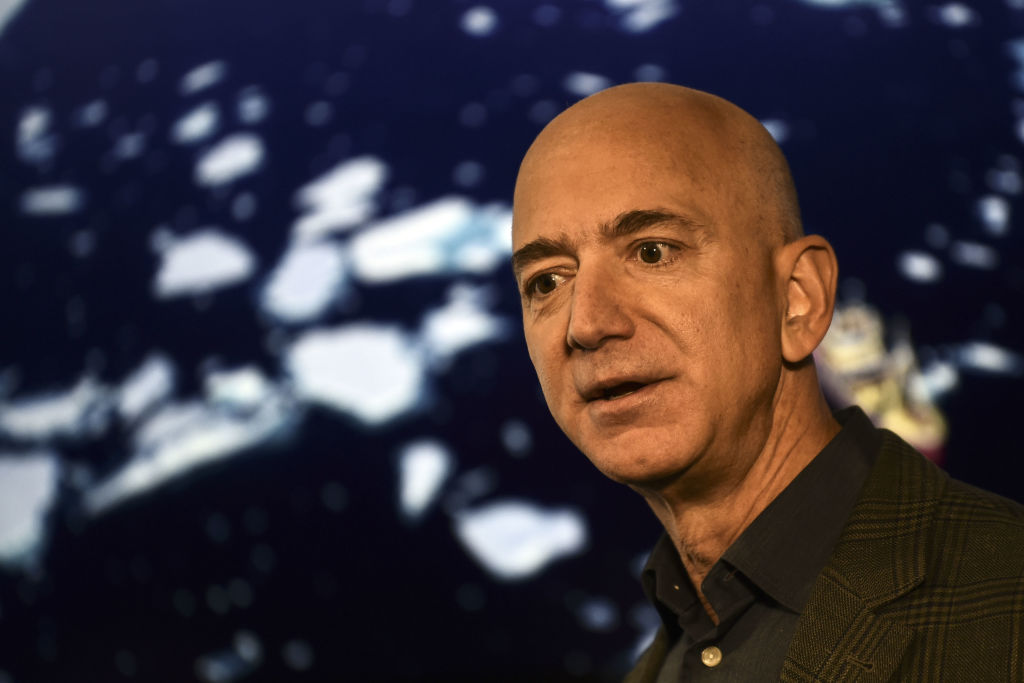

Image Credits: Matthew Staver/Bloomberg / Getty Images

Hello friends, and welcome back to Week in Review!

I’m back from a very fun and rehabilitative couple weeks away from my phone, my Twitter account and the news cycle. That said, I actually really missed writing this newsletter, and while Greg did a fantastic job while I was out, I won’t be handing over the reins again anytime soon. Plenty happened this week and I struggled to zero in on a single topic to address, but I finally chose to focus on Bezos’s Blue Origin suing NASA.

If you’re reading this on the TechCrunch site, you can get this in your inbox from the newsletter page, and follow my tweets @lucasmtny.

The big thing

I was going to write about OnlyFans for the newsletter this week and their fairly shocking move to ban sexually explicit content from their site in a bid to stay friendly with payment processors, but alas I couldn’t help myself and wrote an article for ole TechCrunch dot com instead. Here’s a link if you’re curious.

Now, I should also note that while I was on vacation I missed all of the conversation surrounding Apple’s incredibly controversial child sexual abuse material detection software that really seems to compromise the perceived integrity of personal devices. I’m not alone in finding this to be a pretty worrisome development despite Apple’s intention of staving off a worse alternative. Hopefully, one of these weeks I’ll have the time to talk with some of the folks in the decentralized computing space about how our monolithic reliance on a couple tech companies operating with precious little consumer input is very bad. In the meantime, I will point you to some reporting from TechCrunch’s own Zack Whittaker on the topic which you should peruse because I’m sure it will be a topic I revisit here in the future.

Now then! Onto the topic at hand.

Federal government agencies don’t generally inspire much adoration. While great things have been accomplished at the behest of ample federal funding and the tireless work of civil servants, most agencies are treated as bureaucratic bloat and aren’t generally seen as anything worth passionately defending. Among the public and technologists in particular, NASA occupies a bit more of a sacred space. The American space agency has generally been a source of bipartisan enthusiasm, as has its goal to return astronauts to the lunar surface by 2024.

Which brings us to some news this week. While so much digital ink was spilled on Jeff Bezos’s little jaunt to the edge of space, cowboy hat, champagne and all, there’s been less fanfare around his space startup’s lawsuit against NASA, which we’ve now learned will delay the development of a new lunar lander by months, potentially throwing NASA’s goal to return astronauts to the moon’s surface on schedule into doubt.

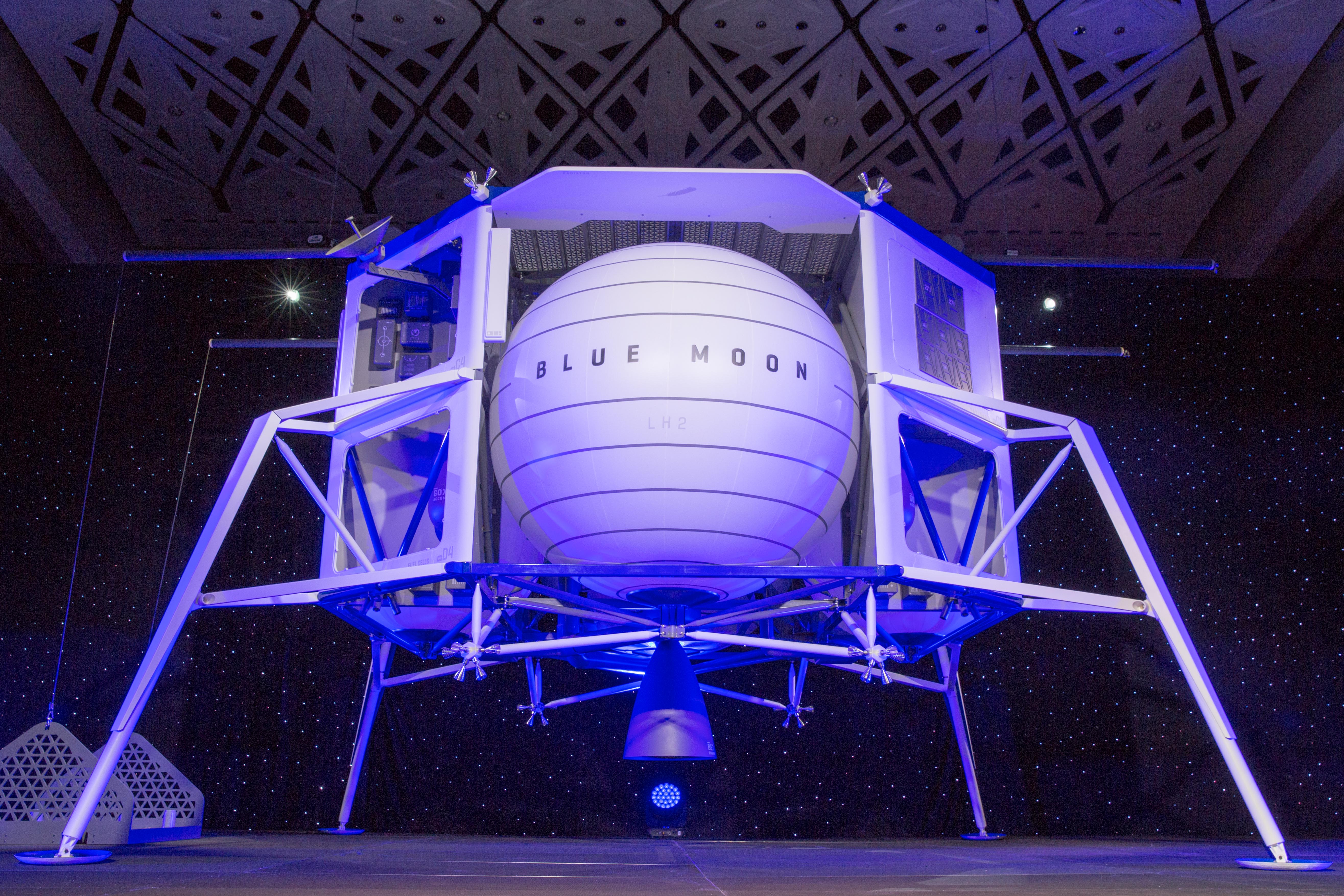

Bezos’s upstart Blue Origin is protesting the fact that they were not awarded a government contract while Elon Musk’s SpaceX earned a $2.89 billion contract to build a lunar lander. This contract wasn’t just recently awarded either, SpaceX won it back in April and Blue Origin had already filed a complaint with the Government Accountability Office. This happened before Bezos penned an open letter promising a $2 billion discount for NASA which had seen budget cuts at the hands of Congress dash its hoped to award multiple contracts. None of these maneuverings proved convincing enough for the folks at NASA, pushing Bezos’s space startup to sue the agency.

This little feud has caused long-minded Twitter users to dig up this little gem from a Bezos 2019 speech — as transcribed by Gizmodo — highlighting Bezos’s own distaste for how bureaucracy and greed have hampered NASA’s ability to reach for the stars:

“To the degree that big NASA programs become seen as jobs programs and that they have to be distributed to the right states where the right Senators live, and so on. That is going to change the objective. Now your objective is not to, you know, whatever it is, to get a man to the moon or a woman to the moon, but instead to get a woman to the moon while preserving X number of jobs in my district. That is a complexifier, and not a healthy one…[…]

Today, there would be, you know, three protests, and the losers would sue the federal government because they didn’t win. It’s interesting, but the thing that slows things down is procurement. It’s become the bigger bottleneck than the technology, which I know for a fact for all the well meaning people at NASA is frustrating.

A Blue Origin spokesperson called the suit, an “attempt to remedy the flaws in the acquisition process found in NASA’s Human Landing System.” But the lawsuit really seems to highlight how dire this deal is to the ability of Blue Origin to lock down top talent. Whether the startup can handle the reputational risk of suing NASA and delaying America’s return to the moon seems to be a question very much worth asking.