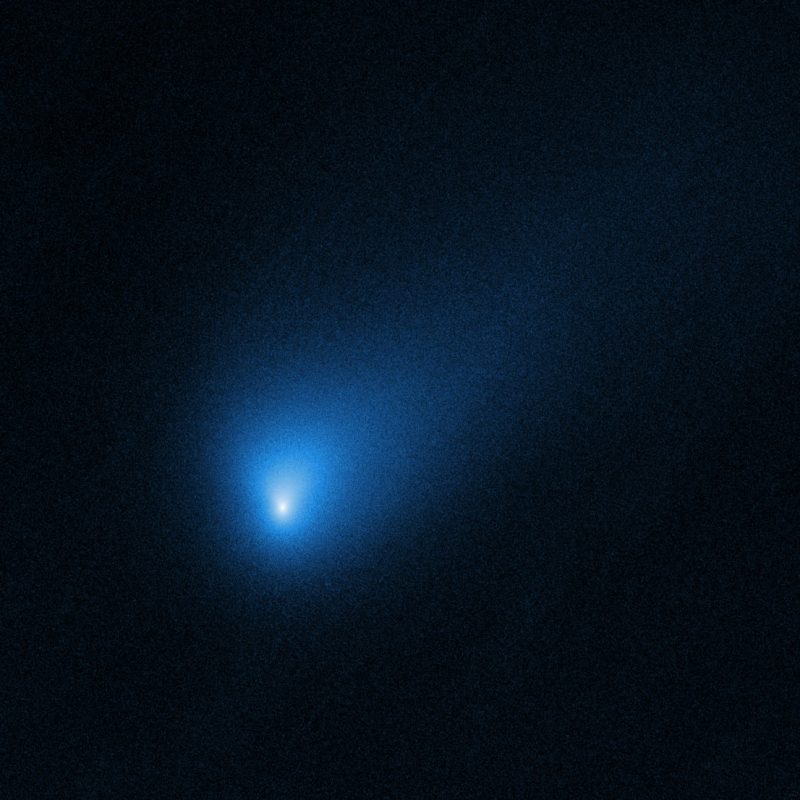

Comets from other star systems, such as 2019 Borisov, visit the sun's neighborhood more frequently than scientists had thought, a new study suggests.

The study, based on data gathered as Borisov zipped by Earth at a distance of about 185 million miles (300 million kilometers) in late 2019, suggests that the comet repository in the far outer solar system known as the Oort Cloud might be full of objects that were born around other stars. In fact, the authors of the study suggest that the Oort Cloud might contain more interstellar material than domestic stuff.

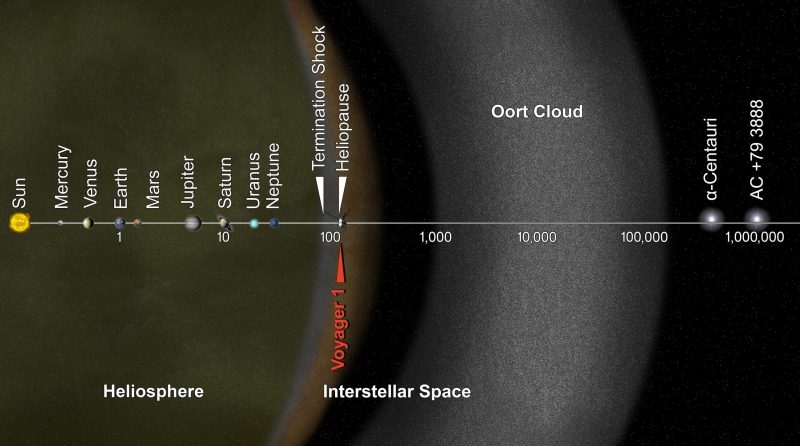

Named after famous Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, who first proved its existence in the 1950s, the Oort Cloud is a spherical shell of small objects — asteroids, comets and fragments — far beyond the orbit of Neptune. The cloud's inner edge is thought to begin about 2,000 astronomical units (AU) from the sun, and its outer edge lies about 200,000 AU away. (One AU is the average Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

No spacecraft has ever visited the Oort Cloud, and it will take 300 years for NASA's farflung Voyager 1 probe to even glimpse the cloud's closest portion.

Related: Interstellar Comet Borisov Shines in New Photo

Astronomers have very limited tools to study this intriguing world, as objects in the Oort Cloud don't produce their own light. At the same time, these objects are too far away to reflect much of the sun's light.

So how exactly did the scientists figure out that there must be so many interstellar objects in the Oort Cloud, and what did Borisov have to do with it?

Amir Siraj, a graduate student at Harvard University's Department of Astronomy and lead author of the study, told Space.com in an email that he could calculate the probability of foreign comets visiting the solar system simply based on the fact that the Borisov comet had been discovered.

"Based on the distance that Borisov was detected at, we estimated the implied local abundance of interstellar comets, just like the abundance of 'Oumuamua-like objects was calibrated by the detection of 'Oumuamua," Siraj said.

The mysterious 'Oumuamua, first spotted by astronomers in Hawaii in October 2017, was the first interstellar body ever detected within our own solar system. The object passed Earth at a distance of 15 million miles (24 million km), about one-sixth of the distance between our planet and the sun. An intense debate about 'Oumuamua's nature ensued, as it wasn't clear at first whether the object was a comet or an asteroid.

Even the detection of a single object can be used for statistical analysis, Siraj said. The so-called Poisson method, which the astronomers used, calculates the probability of an event happening in a fixed interval of time and space since the last event.

Taking into consideration the gravitational force of the sun, Siraj and co-author Avi Loeb, an astronomer at Harvard, were able to estimate the probability of an interstellar comet making its way to Earth's vicinity. They found that the number of interstellar comets passing through the solar system increases with the distance from the sun.

"We concluded that, in the outer reaches of the solar system, and even considering the large uncertainties associated with the abundance of Borisov-like objects, transitory interstellar comets should outnumber Oort Cloud objects (comets from our own solar system)," Siraj added.

So why have astronomers seen just one interstellar comet so far? The answer is technology. Telescopes have only recently gotten powerful enough to be able to spot those small but extremely fast-travelling bodies, let alone study them in detail.

"Before the detection of the first interstellar comet, we had no idea how many interstellar objects there were in our solar system," said Siraj. "Theory on the formation of planetary systems suggests that there should be fewer visitors than permanent residents. Now we're finding that there could be substantially more visitors."

The astronomers hope that with the arrival of next-generation telescopes, such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, currently under construction in Chile, the study of extrasolar comets and asteroids will truly take off.

The new study was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on Monday (Aug 24).