Hollywood’s Socialism Boom: Emboldened Leftists Agitate for Radical Change

With supporters ranging from assistants to power players like Adam McKay, the industry's Democratic Socialists are demanding a fair share for workers (but aren’t necessarily coming for your house in the hills).

BY GARY BAUM, KATIE KILKENNY

The Hollywood Reporter

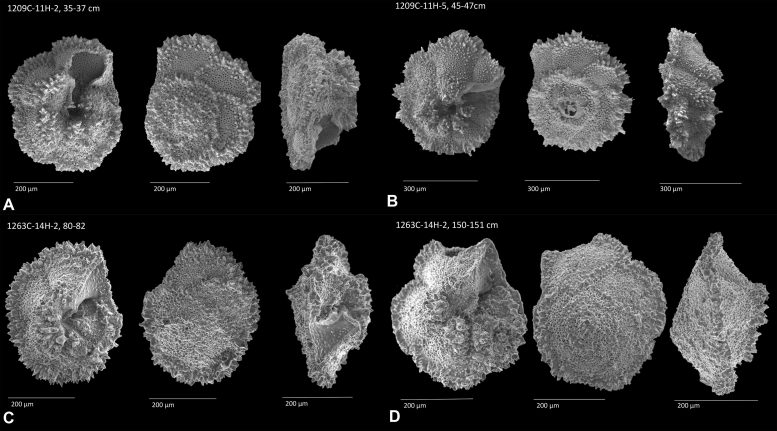

DSA member Noah Suarez-Sikes at a rally. PHOTOGRAPHED BY TARA PIXLEY

LONG READ

The chants are beginning in front of the Chateau Marmont.

It’s the evening of June 25 and masked protesters are marching on the sidewalk outside the legendary Hollywood hangout, which has been under fire for more than a year over escalating allegations of labor mistreatment, including racial discrimination, sexual harassment and mass layoffs at the onset of the pandemic. While a handful of A-listers have registered public disapproval (Jane Fonda recorded a video and Alfonso Cuarón signed a boycotting petition) it’s the industry’s proletariat — assistants, young writers, on-the-make directors and below-the-line crew — who make up a substantial cross-section of the crowd of nearly 100 picketing the Chateau this Friday evening.

“There’s a perception that Hollywood workers are separate from the L.A. community,” says Brenden Gallagher, a writer and a former writers assistant, there with his wife, Claire Downs, also a writer and a former agent assistant. “We have the opportunity to show that we’re all part of the same struggle.”

Many of these industry protesters, a diverse group dressed in various shades of red, are members of the fast-growing Los Angeles chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America and its Hollywood Labor group. “The people who come and stay at this hotel, who are our bosses or the people who we’re working for, they interact with these [hotel] workers on a daily basis,” says Neda Davarpanah, a DSA member on the leadership board of Hollywood Labor and a writers assistant. “Whether you’re working in a writers room or working in a hotel, we need to stand together.”

In the past few years, a new wave of Hollywood leftists seeking transformational change has been growing in number at the Los Angeles chapter of DSA. These entertainment workers believe the industry’s entrenched style of corporate neoliberalism, with industry moguls wielding outsize political power and the glorification of young artists living on little while attempting to achieve their dreams, needs structural recasting, not to mention a narrative correction. The Hollywood Reporter spoke to more than two dozen of such workers. Fueled by the success of openly socialist politicians like Sen. Bernie Sanders, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and recently elected L.A. City Councilmember Nithya Raman, as well as justice movements roiling the industry, the chapter has tapped into the frustrations of an idealistic rank and file.

Outside Chateau Marmont, marching in support of Unite Here Local 11. “It was very shocking to me that people had normalized the degree to which they were disrespected and being taken advantage of for their labor, and it just doesn’t have to be this way,” says Suarez-Sikes.

Meanwhile, higher-profile DSA members, like Catastrophe‘s Rob Delaney, have helped lift the organization’s profile. “I joined because I want more democracy in the U.S.,” Delaney, a lifetime DSA member, says. “Voting rights are under (a very successful) attack and, even more than that, I very seriously believe the workers should own and control the means of production.” The L.A. chapter’s Hollywood Labor subcommittee sprung up four years ago to meet the rising interest. Now around 1,000 people subscribe to the group’s Action Network mailing list. Many work as screenwriters, writers assistants, script coordinators, script supervisors and animation employees.

“In a country and in a city with crushing, devastating income inequality, it’s no longer ‘left-wing’ to demand living wages, universal health care and rent control,” says self-described Democratic Socialist, DSA-LA supporter and The Big Short director Adam McKay. “It’s a bare minimum. When I looked around, I found some incredible groups committed to fighting the big dirty money rotting out our communities. And DSA-LA, for me, is at the top of that list.”

DSA-LA members are happy to call out more centrist Hollywood labor groups. They will tell you that SAG-AFTRA — a body that, as DSA partisans are quick to remind you, once elected as its president Ronald Reagan — is captive to ladder-pulling stars who pay far too little of their income in dues. They view industry diversity initiatives as important but rather empty gestures when entry-level pay has remained paltry over decades, even as student loan debt and rents soar, creating a higher entry barrier for those with less access to family wealth. To them, Netflix shouldn’t be sainted for its $100 million announced investment in Black community financial institutions in 2020, at least so long as CEO Reed Hastings is still a financial backer and fervent promoter of the charter school movement, which some DSA members consider a capitalist hijacking of public education.

The group, which tends to reference the byword “dignity” in conversation, appeals to those breaking in who are increasingly vocal against workplace harassment, bullying and other forms of exploitation and who believe change should have happened years ago and are no longer willing to accept the status quo as the price of admission. “I’ve met people who were covering three desks and never had a moment to go to the bathroom; at bar after bar you hear from people who go, ‘Yeah, my job makes me want to kill myself. But maybe someday I’ll be a big producer,’ ” says member Noah Suarez-Sikes, who has worked as a producer’s assistant and is currently writing a pilot about Ayn Rand’s time in the entertainment business. (He wielded a bullhorn at the Chateau protest.) “It was very shocking to me that people had normalized the degree to which they were disrespected and being taken advantage of for their labor, and it just doesn’t have to be this way.”

While DSA-LA members see its agenda as part of a wave of equity-focused movements (including #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and #PayUpHollywood), the organization takes a wide-net approach. In the process, the group is wrestling with how to advance its causes while building its hoped-for solidarity in a business where folks inhabit roles as divergent — and differently compensated — as showrunner and PA. “The goal with DSA isn’t to create a class war, the goal is to create a dialogue and conversation with not only those that are below the line but also those above the line,” says postproduction supervisor and chapter member Albert Andrade.

Konstantine Anthony, a member who was elected to the Burbank City Council in 2020, spent several years working a union job at Universal Studios’ House of Horrors haunted maze as a werewolf before turning to stand-in gigs on sitcoms like New Girl and Parks and Recreation. He sees DSA as a perpetual outsider best able to agitate at the margins while other activist entities, like Time’s Up, strike deals or compromise in hopes of getting their way. “DSA stands with their flag post on the other side, saying, ‘No, we can go farther,’ continuing to instigate, in the good sense of the word. Fighting for a little bit more,” he says.

“I think there’s a lot of people that are like, ‘I want to buy a house in the Palisades — don’t yell at me.’ No one’s stopping you,” assures writer-producer Nick Adams (BoJack Horseman, Black-ish). “If you’re buying five houses, maybe we want to talk to you …”

***

The latest iteration of DSA’s L.A. chapter began in 2010, but remained a somewhat sleepy local until Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign brought brand recognition to socialism (in 2015, the local chapter had 270 members; by 2017, that number shot to 800 and now there are 5,500 members). Some on the left who reacted to the Trump regime not as a freak aberration but instead a manifestation of entrenched issues have increasingly turned to DSA as a vehicle for change. The same contingent views the blue-wave Biden era as a potential sleepwalk toward calamity if the left grows too complacent.

The Hollywood Labor subcommittee has since found itself involved in several actions, from efforts to end Hollywood’s ties to the police to the Chateau boycott. The pandemic was its own radicalizing force, as industry workers lost their jobs and protests for racial justice swept the country. DSA-LA says it started 2020 with about 1,700 members and over the course of the year brought on thousands more. “It’s been a clarifying moment where a lot of people can see these institutional problems come to light,” Davarpanah says of COVID-19.

The chapter’s rise indicates just how far Hollywood has come from the red-baiting Blacklist era, which infamously drove many on the left underground. “The socialists can come in now without the taint of historical communism,” explains Brandeis professor Thomas Doherty, author of the Blacklist history Show Trial. “They can allege that they are for a purer vision of economic opportunity and redistribution. … Socialism’s not the dirty word it was in 1955.”

Still, today’s DSA members bear some similarities to the industry’s leftists of earlier eras. Nearly a century ago, says film historian and Tender Comrades co-author Patrick McGilligan, Hollywood knowledge workers like readers and story editors formed the “militant factions” of that era’s intellectual leftism. “They were overworked and underpaid,” he says, adding, “In these fields, you get the very educated, who understand the contradictions of their own environment.” Today, Hollywood Labor’s big tent includes a spectrum of ideologies, from anarcho-communist to progressive Democrat. The backgrounds of members vary, too: working- and middle-class, with conservative, liberal and mainly moderate political family upbringings.

Some say they are very outspoken about being a socialist, while those starting out in their careers tend to be cautious. Certain members are well versed in Marx; one casually quotes Fred Hampton. Others are more issue-driven.

“Have I read a lot of socialist theory? No,” says Big Mouth and Sunnyside actor and comedian Joel Kim Booster, who came into the fold after supporting Sanders. “I believe we should house the unhoused. I believe we should have universal health care.”

***

DSA-LA isn’t just riding a favorable political wave. Its community-organizing outreach includes launching a series of get-togethers that it has branded Champagne Socialism, a take on the industry’s ubiquitous networking drinks: “You come and talk about your challenges at work. Your production company that doesn’t have an HR department. That you’ve been promised opportunities instead of pay. The lies you’ve been told,” explains Helen Silverstein, a member who’s a script doctor and a writers assistant at 96 Next, a mixed-media and interactive studio. In March, the group helped organize an “Anticapitalism for Artists” event that featured a talk by Sorry to Bother You director Boots Riley, workshops and community discussions. Also during lockdown, Hollywood Labor launched The Redlist, a socialist answer to Franklin Leonard’s The Black List that foregrounds scripts that “promote left-wing narratives in entertainment, and … highlight the experiences of the poor, the disenfranchised and the oppressed.” (Members point to Snowpiercer and Us as model Redlist films.) Now the group is planning a rollout of its own cheeky renditions of that L.A. standby, Star Maps. These will be introductory guides to workers who are new to the industry that may detail local labor laws and explain “meetings” culture. “Hollywood Labor’s goal is to bring more workers over to our socialist program — socially,” explains Daniel Dominguez, an organizer for health care unions and a DSA chapter member.

Adam Ruins Everything star Adam Conover, who is not a DSA-LA member but is supportive of the group, says that he sees “DSA-LA, and especially their Hollywood Labor committee, as part of the overall political awakening of Hollywood labor,” noting that the group’s “most important” ongoing work is as an organizing entity that can prod the industry’s many and often divergent entertainment unions.

An April 2021 rally in support of Donut Friend workers’ unionizing efforts. COURTESY OF DSA LA

DSA-LA members want to unionize video game and VFX workers, whose fields largely haven’t been organized. The group also encourages members already in unions to become more involved, run as delegates and push more aggressive organizing and reforms. Some believe that unions should take a long view and advocate politically for single-payer health care so that, if such a system were implemented, they could cease bargaining for health benefits and focus on quality-of-life improvements. Those familiar with SAG-AFTRA add that they want top-earning actors to pay more dues.

Recently, DSA-LA union members participated in efforts to separate the union federation AFL-CIO, which represents Hollywood unions, from a police union under its umbrella (they have not yet succeeded). If DSA-LA organizers do ever gain meaningful power in the industry and its unions, “they’ll work to divest from things like police unions,” says writer, actor and DSA-LA member Sarah Sherman (Magic for Humans). Ridding cops from on-set production work — where they enforce shoot perimeters and direct traffic — has become a rallying cry. Group members also joined Black Lives Matter’s protests against former L.A. County District Attorney Jackie Lacey, who lost her election to progressive reformer George Gascón last year.

The Nov. 7, 2020, Rally and March to Defend Each Other & Demand Democracy. “In a country and in a city with crushing, devastating income inequality, it’s no longer ‘left-wing’ to demand living wages, universal health care and rent control,” says Democratic Socialist and The Big Short director Adam McKay. COURTESY OF DSA LA

Adam West, a longtime costumer, union representative and DSA chapter member, says they want entertainment industry workers to remember that “the power rests in the membership of the unions — not in the elected leaders, not in the hired representatives, not in the overall international structure.”

Another popular talking point for members: how Hollywood’s much-touted diversity efforts ring hollow when early-career industry salaries remain so low, a point IATSE members (and particularly those in Local 871, which represents writers assistants and script coordinators and has members in DSA-LA) are also making with their #IALivingWage campaign. “So many of those studio and agency jobs require having parents who can pay your rent while you do that job,” says writer and producer Mitra Jouhari (Big Mouth, Three Busy Debras). “If you don’t have that luxury, you can’t do that job.” Sherman adds that “the landscape has become so much more precarious” than it was decades ago, when today’s upper-management echelon entered the business. “The student debt is 20 million times worse,” she says of the more than 100 percent increase since a decade ago. “These people need to be paid [better]. There needs to be a $25 minimum wage. I don’t know what these old farts’ memory is of when they were young, but it’s not the same.”

***

Since it began four years ago, Hollywood Labor has offered a gateway for industry workers to get involved in local issues, and for those looking to branch out, DSA-LA has committees dedicated to electoral politics, health care justice, climate justice, housing and homelessness, and a number of other areas. That DSA-LA is not myopically focused on Hollywood itself, and shows industry workers they can repurpose their professional skills for the benefit of a larger community, can be a draw. “With DSA, there were all these conversations of being in L.A. that were not just about networking,” says Hollywood Labor leadership board member and screenwriter Alex Wolinetz. “They cared about local issues.” Andrade, an L.A. native, says he’s used his postproduction supervising skills to aid the chapter’s Neighborhood Council group, which runs DSA members as candidates in neighborhood council elections, which has been “really the most satisfying thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

Indeed, though its national organization is not a political party, DSA-LA puts an emphasis on running candidates in local elections to further realize its goals. Anthony was elected as a Democrat to the Burbank City Council with a platform focused on housing justice and infrastructure, among other issues. DSA-LA member and former Time’s Up Entertainment executive director Raman’s victorious, homelessness-focused 2020 campaign for City Council was a “touch point” for many in the chapter, says Dominguez. (Raman, whose husband is Modern Family executive producer Vali Chandrasekaran, is facing an incipient recall effort from some who are discontented with her approach to the unhoused and also her ties to DSA-LA.) Adams recalls seeing Raman at an event early in her campaign and thinking, “This is exactly why I joined [DSA-LA].” He adds, “It’s hard for me to see the school system, the homelessness, the traffic, the air quality, the inequality. That’s where I try to focus my energy because I feel like it’s doable. Having a more progressive L.A. City Council is doable.”

This local work occasionally intersects with L.A.’s network of lefty grassroots organizations such as KTown for All and Ground Game LA. The “NOlympics” campaign to raise awareness about the Games exacerbating displacement, among other concerns, and to build community opposition to the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic Games began in DSA-LA’s Housing and Homelessness committee, and now more than two dozen organizations, including Black Lives Matter, have joined the effort.

DSA-LA organizers who work in the industry say they want to push the entertainment business — and its unions — to start weighing in more on local politics. “I want to get people in Hollywood more involved in the issues of the community, because Hollywood is very insular,” says Suarez-Sikes. “And to the point that it’s often very removed from Los Angeles, but in reality, it all interacts, it all intersects.” Mary Tyler Moore Show actor Ed Asner, a longtime DSA member who once served as president of SAG-AFTRA, notes, “If you can’t liberalize the politics at home, you’ll never do it at a distance.”

Some members say DSA needs to focus on efforts specifically for communities of color and making inroads with more working-class people in Hollywood, and not just “lofty lefty educated writer types,” in the words of Adams. Asner says, “I would like to see the [group] spreading more widely than it is. I’m unimpressed with the numbers” of DSA-LA’s growth.

Doherty contends that DSA-LA’s Hollywood union efforts present “a classic wedge point” in American organized labor, exposing a tension between blue-collar lifers and younger activists who want revolutionary change. Suarez-Sikes acknowledges that, even within DSA itself, “internal cohesion” can be a challenge: The group “sometimes has trouble activating its members in the way that smaller, but less inclusive, organizations are able to,” he says. Colorist and editor Sean Broadbent adds that the group needs to prepare for critics to portray their work as divisive: “The challenge is really to stay rooted with each other and with the people that we hope to organize so that we’re not seeding the ground for the counterrevolution,” he says with a laugh.

And for some, there’s a wariness of co-option by the market forces it’s rebelling against. “DSA will have to guard against becoming a [business] networking organization” as it grows, warns member Robert Funke, creator of On Becoming a God in Central Florida. “They will have to impart class solidarity into an industry that disincentivizes it at all levels and in all areas.”

Additional reporting by Kirsten Chuba.

This story first appeared in the July 16 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.