The Big Scary ‘S’ Word: why are people so terrified of socialism?

In a new documentary, film-maker Yael Bridge looks back and forward to see why some people have been so repelled by socialism and how things might change in the future

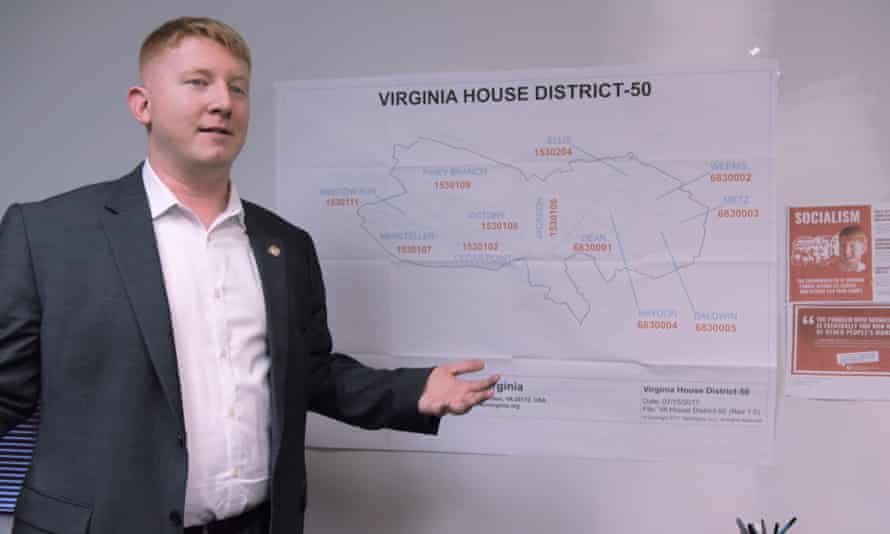

Lee Carter is a US Marine Corps veteran and Lyft driver. He is also a socialist. After he suffered a workplace injury, realised the system was broken and Googled “How do you run for office?”, he stood for election to the Virginia state assembly.

A campaign leaflet from his opponent displayed the faces of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong – and Carter, who told film-maker Yael Bridge: “It’s from another era entirely. I was born in ’87, I don’t remember the Berlin wall falling, so the ‘red scare’ – anybody who uses the big scary ‘s’ word is automatically Stalin – it just doesn’t work any more.”

Bridge took his observation for the title of her soon-to-be-released documentary, The Big Scary “S” Word, which tells how Carter beat the Republican incumbent to become the lone socialist in the Virginia state assembly (though after two terms he lost a primary re-election bid in June) and explores the unexpected history of the American socialist movement.

Her film makes a persuasive case that while America famously embraces capitalism red in tooth and claw, the emergence of the leftwing senator Bernie Sanders in the 2016 presidential election was no anomaly but part of an equally proud tradition. Far from contradicting the US constitution, socialism has often been seen as furthering its ideals.

Bridge, based in Oakland, California, said by phone: “When you think about socialism, if you don’t just think about Russia or China or Cuba, people think about social democracies in Scandinavia. But we don’t need to look to all those other countries to find examples of socialism or success stories, so it was important to me to forefront those in the film.”

Few words are more loaded than socialism. It is defined by Merriam-Webster as “any of various economic and political theories advocating collective or governmental ownership and administration of the means of production and distribution of goods”.

Misunderstandings about what socialism means are widespread in the United States. One young person in the film puts it: “It’s kind of like a more mediocre version of communism, I think?”

For Republicans it has become the ultimate trigger word, guaranteed to provoke a visceral recoil. Last year’s Conservative Political Action Conference, for example, was themed “America vs socialism” and included sessions such as “Socialism: Wrecker of Nations and Destroyer of Societies”. Senator Mike Lee told attendees: “They’re talking about having the government become your healthcare provider, your banker, your nanny, your watchdog. Having the government lie to you and spy on you.”

So it is remarkable when the origins of the Republican party are outlined by one of the film’s interviewees, John Nichols, author of The “S” Word, a history of American socialism. He argues that the ideology enjoyed a popular high in the United States in the 1840s, when a group of immigrants who settled in Ripon, Wisconsin, started to form a communal society in which wealth was shared. They built communal houses and argued for land redistribution so poor people could have farms.

The people of Ripon formed a new political party that would oppose the expansion of slavery. Nichols says: “When we talk about the history of socialism in America, we certainly would say that the socialist party was founded by socialists, but we should also say that the Republican party was founded by socialists.”

Bridge, 39, adds: “There’s this building called the little white schoolhouse, which is a museum now as the founding place of the Republican party, so there’s Trump and George W Bush and all these big posters for Republicans – but it’s funny also knowing that the little white schoolhouse was indeed a schoolhouse for socialists in the 1800s.”

Bridge, whose previous film, Saving Capitalism, followed the former labour secretary Robert Reich as he talked to people disillusioned with the political status quo, found another surprise in North Dakota, a Republican stronghold where Donald Trump beat Joe Biden last year by 33 percentage points. It is the only state with a government-owned general service bank.

“It was set up by socialists to be more democratic and help the people there and now most of the Republican leadership in that state come out of the bank and they don’t want anything to do with socialism. They don’t like talking about their early days history. But it’s clear today it was socialists setting up that bank and making it so successful.”

Another subject in the film, Eric Foner, a history professor at Columbia University, testifies that Republican president Theodore Roosevelt’s platform was to the left of Sanders, advocating for a national health service, unemployment insurance and controls over corporations, though he did not call himself a socialist.

In the Great Depression, Democratic president Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal adopted ideas from the socialist party and provided social security, the first minimum wage, unemployment compensation and millions of public sector jobs – “classical socialist things”, as one interviewee puts it.

The 1963 march on Washington was in fact the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom”. Foner argues that the civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr increasingly demanded fundamental changes in the economic system, but this radical edge is too often rubbed smooth by today’s efforts to sanitise him as a cosy symbol of racial reconciliation.

Bridge observes: “I don’t think this is an experience unique to the United States in that we whitewash all of our history and we defang it and we make it less radical and then we bring it into the fold.

“So now everyone loves Martin Luther King and he’s so fantastic and revered and what a wonderful human and we can certainly agree with all of his ideas. But he was certainly not that popular during his day and increasingly over the course of his life, when he saw economic inequality as a great barrier to racial equality and started using language of capitalism and socialism, that was very threatening. It was the beginning of the end.”

Barack Obama was branded a socialist for making relatively modest changes to the healthcare system. But the eruption of Sanders, an independent senator for Vermont and self-declared democratic socialist, in the 2016 Democratic primary shook American politics. Since then membership of the once dormant Democratic Socialists of America has soared to nearly 100,000. Union membership is also growing fast.

Now 79, Sanders is chair of the powerful Senate budget committee, while his ally the New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, 31, has built a huge following. In June the socialist India Walton won a Democratic primary that made her virtually certain to become the mayor of Buffalo, New York.

The comedian Bill Maher once noted that the United Nations’ annual world happiness rankings were led by “socialist-friendly” countries like Finland, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Canada, asking: “If socialism is such a one-way ticket to becoming the nightmare of Venezuela, then why do all the happiest countries in the world embrace it?”

Even within the US, it can be argued that the publicly funded elements of education, healthcare, media, transport and welfare – including a new child tax credit that aims to cut child poverty in half – are inspired by socialism. Yet the ideology is still used as a bogeyman by Republicans and rightwing media who point to the Soviet Union, Cuba, Venezuela and other countries to warn that it would destroy America.

Bridge responds: “I’m not an expert on any of those places but we don’t need to look to those examples as failures; we can look in our own country for successes like the Bank of North Dakota. They are able to have really fantastic public schools and universities and libraries and their infrastructure is really strong because there’s no private interest taking the money out and the people get to have a say in how that money is invested.

“We can look at work-around co-ops and those are incredibly successful. Frequently, they’re shown to be more productive then privately owned businesses because when you are your own boss and you’re able to reap the benefits of your work, you’re going to be working harder and that’s just not what we’re seeing right now at all.”

Polls consistently show a majority of millennials prefer socialism over capitalism. Bridge says: “What I found was that it’s just incredibly generational. The cold war was so powerful in this country and so many resources were spent making that word and those ideas just completely abhorrent and scary.

“People are really scared and so they don’t think, ‘oh, socialism, I’ll have healthcare’; they think, ‘Oh, socialism, that’s horrible, they’re going to come they’re going to take my house and I’m going to be wearing a uniform.’ I saw it so clearly when I would be traveling, meeting with different socialists in different parts of the country and there would be people over 75 or under 35 and such a small percentage in the middle.”

The Big Scary “S” Word also considers the big scary “c” word: capitalism. It is, after all, America’s secular religion; it is as hard to imagine a socialist president as an atheist one. Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic speaker of the House of Representatives, declared, “We’re capitalists, that’s just the way it is”, while the progressive senator Elizabeth Warren has called herself a “capitalist to my bones”.

But Bridge turns the tables: “When people say, oh, name a socialist country that’s been successful, well, name a capitalist country that’s been successful. I look around, I don’t see any country that doesn’t have vast numbers of people starving. Where I live in Oakland, the houseless community is just expanding. I don’t see capitalism solving it in any meaningful way and, if you dig a little deeper, it looks like capitalism is particularly ill-equipped to solve those problems at all.”

The film notes that five individuals own more wealth than 3.5 billion people, half the world’s population. “The profit motive is great at generating a large degree of wealth but it hoards it in the hands of certain people and that is inherently undemocratic,” Bridge says. “If we want to live in a democratic society, which I do and which this country was founded on, you really just can’t have that large amount of inequality.

“I think capitalism and democracy are incompatible. When you have more money, you use your wealth to help write the laws and legislation and put in judges and politicians that are going to protect your interests, and so it becomes a vicious cycle.”

Later segments of the film detail how capitalism has failed to grapple with the coronavirus pandemic and climate crisis. Fossil fuel giants’ addiction to growth and profits took priority over the survival of the planet. Sanders, Ocasio-Cortez and others endorse a “green new deal” which, naturally, Republicans portray as a radical socialist plot against America.

Bridge reflects: “The profit motive is making it harder and harder for us to organise collectively, and we are all on one planet with the same amount of limited resources. If we are not able to share them and people are only driven by profit motive to succeed, we’re not all going to make it.”

The Big Scary “S” Word is released in US cinemas and on demand on 3 September with a UK release to be announced