A Key Challenge to Harvesting Fusion Energy on Earth

A key challenge for scientists striving to produce on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars is preventing what are called runaway electrons, particles unleashed in disrupted fusion experiments that can bore holes in tokamaks, the doughnut-shaped machines that house the experiments. Scientists led by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have used a novel diagnostic with wide-ranging capabilities to detect the birth, and the linear and exponential growth phases of high-energy runaway electrons, which may allow researchers to determine how to prevent the electrons’ damage.

Initial energy

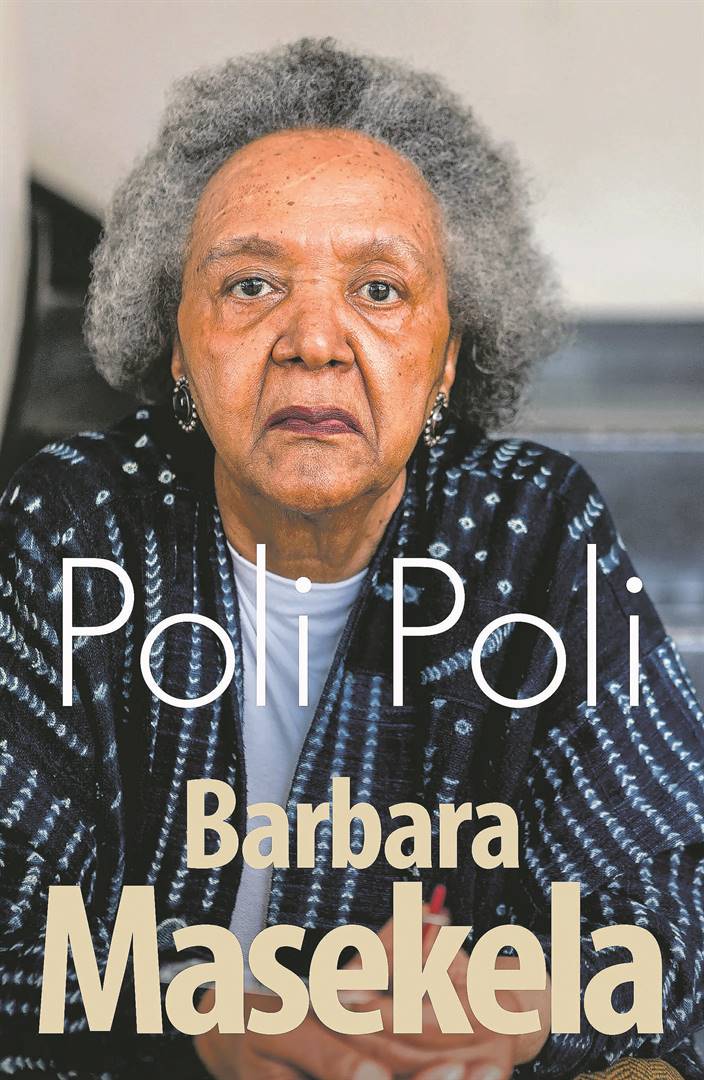

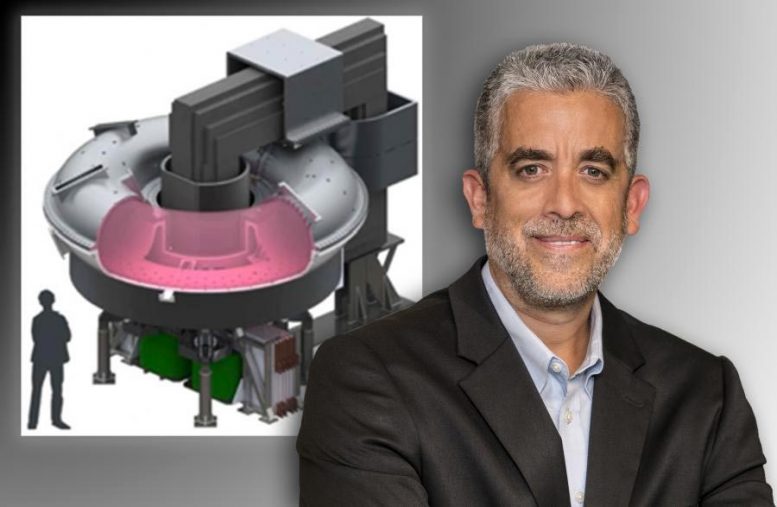

“We need to see these electrons at their initial energy rather than when they are fully grown and moving at near the speed of light,” said PPPL physicist Luis Delgado-Aparicio, who led the experiment that detected the early runaways on the Madison Symmetric Torus (MST) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The next step is to optimize ways to stop them before the runaway electron population can grow into an avalanche,” said Delgado-Aparicio, lead author of a first paper that details the findings in the Review of Scientific Instruments.

Fusion reactions produce vast amounts of energy by combining light elements in the form of plasma — the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei that makes up 99 percent of the visible universe. Scientists the world over are seeking to produce and control fusion on Earth for a virtually inexhaustible supply of safe and clean power for generating electricity

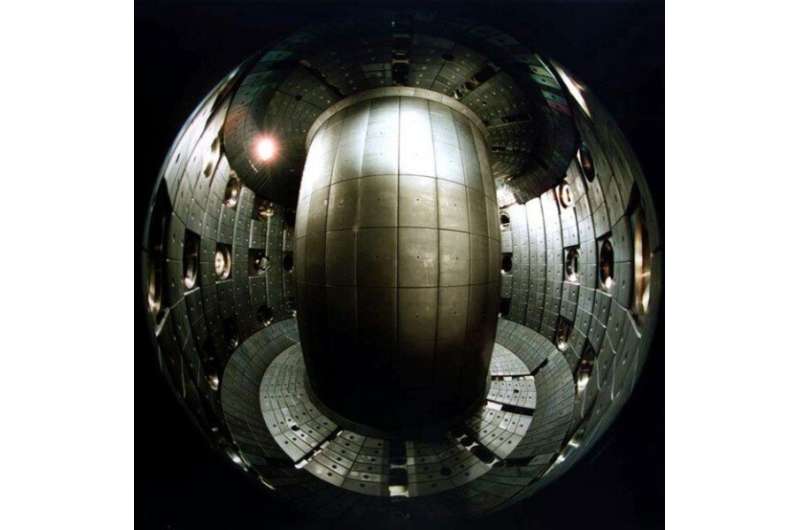

Physicist Luis Delgado-Aparicio with figure of Madison Symmetric Torus from his paper. Credit: Photo and collage by Elle Starkman/Office of Communications

PPPL collaborated with the University of Wisconsin to install the multi-energy pinhole camera on MST, which served as a testbed for the camera’s capabilities. The diagnostic upgrades and redesigns a camera that PPPL had previously installed on the now-shuttered Alcator C-Mod tokamak at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and is unique in its ability to record not only the properties of the plasma in time and space but its energy distribution as well.

That prowess enables researchers to characterize both the evolution of the superhot plasma as well as the birth of runaway electrons, which begin at low energy. “If we understand the energy content I can tell you what is the density and temperature of the background plasma as well as the amount of runaway electrons,” Delgado Aparicio said. “So by adding this new energy variable we can find out several quantities of the plasma and use it as a diagnostic.”

Novel camera

Use of the novel camera moves technology forward. “This certainly has been a great scientific collaboration,” said physicist Carey Forest, a University of Wisconsin professor who oversees the MST, which he describes as “a very robust machine that can produce runaway electrons that don’t endanger its operation.”

As a result, Forest said, “Luis’s ability to diagnose not only the birth location and initial linear growth phase of the electrons as they are accelerated, and then to follow how they are transported from the outside in, is fascinating. Comparing his diagnosis to modeling will be the next step and of course a better understanding may lead to new mitigation techniques in the future.”

Delgado-Aparicio is already looking ahead. “I want to take all the expertise that we have developed on MST and apply it to a large tokamak,” he said. Two post-doctoral researchers who Delgado-Aparicio oversees can build upon the MST findings but at WEST, the Tungsten (W) Environment in Steady-state Tokamak operated by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) in Cadarache, France.

Range of uses

“What I want to do with my post-docs is to use cameras for a lot of different things including particle transport, confinement, radio-frequency heating and also this new twist, the diagnosis and study of runaway electrons,” Delgado-Aparicio said. “We basically would like to figure out how to give the electrons a soft landing, and that could be a very safe way to deal with them.”

Reference: “Multi-energy reconstructions, central electron temperature measurements, and early detection of the birth and growth of runaway electrons using a versatile soft x-ray pinhole camera at MST” by L. F. Delgado-Aparicio, P. VanMeter, T. Barbui, O. Chellai, J. Wallace, H. Yamazaki, S. Kojima, A. F. Almagari, N. C. Hurst, B. E. Chapman, K. J. McCollam, D. J. Den Hartog, J. S. Sarff, L. M. Reusch, N. Pablant, K. Hill, M. Bitter, M. Ono, B. Stratton, Y. Takase, B. Luethi, M. Rissi, T. Donath, P. Hofer and N. Pilet, 2 July 2021, Review of Scientific Instruments.

DOI: 10.1063/5.0043672

Two dozen researchers participated in the research with Delgado-Aparicio and co-authored the paper about this work. Included were seven physicists from PPPL and eight from the University of Wisconsin. Joining them were a total of three researchers from the University of Tokyo, Kyushi University and the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology in Japan; five members of Dectris, a Swiss manufacturer of detectors; and one physicist from Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin.

Support for this work comes from the DOE Office of Science.

Nuclear fusion, if scientists ever manage to figure it out, could provide a bounty of clean energy — and potentially a clear path in the transition away from fossil fuels. But the technology to recreate the sort of reaction happening inside of stars in a controlled setting on Earth has proven tricky, to say the least. That said, research published last month in the journal Nature may represent a significant step forward. The physicists demonstrated that the Wendelstein 7-X, a nuclear fusion device in Germany, can successfully contain temperatures twice as high as the core of the Sun — and they’re utterly thrilled.

“It’s really exciting news for fusion that this design has been successful,” study coauthor and Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) physicist Novimir Pablant said in a press release. “It clearly shows that this kind of optimization can be done.”

The Wendelstein 7-X is a device called a stellarator — a kind of plasma containment device that was first developed in the 1950s but largely fell out of favor because its complex, twisted design is notoriously bad at keeping the heat generated by a fusion reaction from leaking out. Because of that, most facilities are developing donut-shaped tokamaks which retain heat better and, in some tests, have generated temperatures over ten times hotter than the Sun’s core.

But a practical stellarator would let scientists circumvent some of the other headaches caused by tokamaks, which can struggle to stabilize the super-hot plasma that drives fusion reactions. And that prospect has the team extremely excited.

“It’s been very exciting for us, at PPPL and all the other US collaborating institutions, to be part of this really exciting experiment,” Advanced Projects Department head at the PPPL David Gates said in the release. “[Pablant’s] work has been right at the center of this amazing experimental team’s effort. I am very grateful to our German colleagues for so graciously enabling our participation.”

READ MORE: PPPL physicist helps confirm a major advance in stellarator performance for fusion energy [Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory]

More on nuclear fusion: Scientists Are On the Edge of a Fusion Power Breakthrough

Negative triangularity—a positive for tokamak fusion reactors

by US Department of Energy

Tokamak devices use strong magnetic fields to confine and to shape the plasma that contains the fuel that achieves fusion. The shape of the plasma affects the ease or difficulty of achieving a viable fusion power source. In a conventional tokamak, the cross-section of the plasma is shaped like the capital letter D. When the straight part of the D faces the "donut hole" side of the donut-shaped tokamak, this shape is called positive triangularity. When the plasma cross-section is in a backwards D shape and the curved part of the D faces the "donut hole" side, then this shape is called negative triangularity. New research shows that negative triangularity reduces how much the plasma interacts with the plasma-facing material surfaces of the tokamak. This finding points to critical benefits for achieving nuclear fusion power.

One of the challenges in fusion energy science and technology is how to build future power plants that control plasmas many times hotter than the sun. At these extreme temperatures, interactions of the plasma with the material walls of the power reactor must be controlled and minimized. Unwanted interactions occur due to turbulence in the boundary region of the plasma. This research shows that the boundary turbulence in negative triangularity plasmas is much reduced when compared with that occurring in plasmas with a positive triangularity shape. As a result, the unwanted interactions with the plasma-facing walls are also much reduced, leading in principle to longer lifetimes for the wall and a reduction in the risk of damage to the wall, something that could shut down a reactor.

Scientists know that, in tokamak fusion devices, core plasma shapes with negative triangularity exhibit a substantial increase in energy confinement compared to plasmas with positive triangularity. Negative triangularity plasma shapes also show reductions in the fluctuation levels of the core electron temperature and density. This by itself makes negative triangularity plasmas promising candidates for a future fusion power reactor.

The new research reported here shows that the sign and degree of triangularity also have a large effect on plasma edge dynamics and power and particle exhaust properties, but scientists know relatively little about such effects. These experiments at the Tokamak à Configuration Variable (TCV), located at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, revealed a strong reduction of boundary-plasma fluctuations and plasma interaction with the facing wall for sufficiently negative triangularity values. The researchers observed the effects across a wide range of densities in both inner-wall-limited and diverted plasmas. This strong reduction in plasma-wall interaction at sufficiently negative triangularity strengthens the prospects of negative triangularity plasmas as a potential reactor solution.

The research was published in Nuclear Fusion.

Cross-pollinating physicists use novel technique to improve the design of facilities that aim to harvest fusion energy

More information: W. Han et al, Suppression of first-wall interaction in negative triangularity plasmas on TCV, Nuclear Fusion (2021). DOI: 10.1088/1741-4326/abdb95

Provided by US Department of Energy