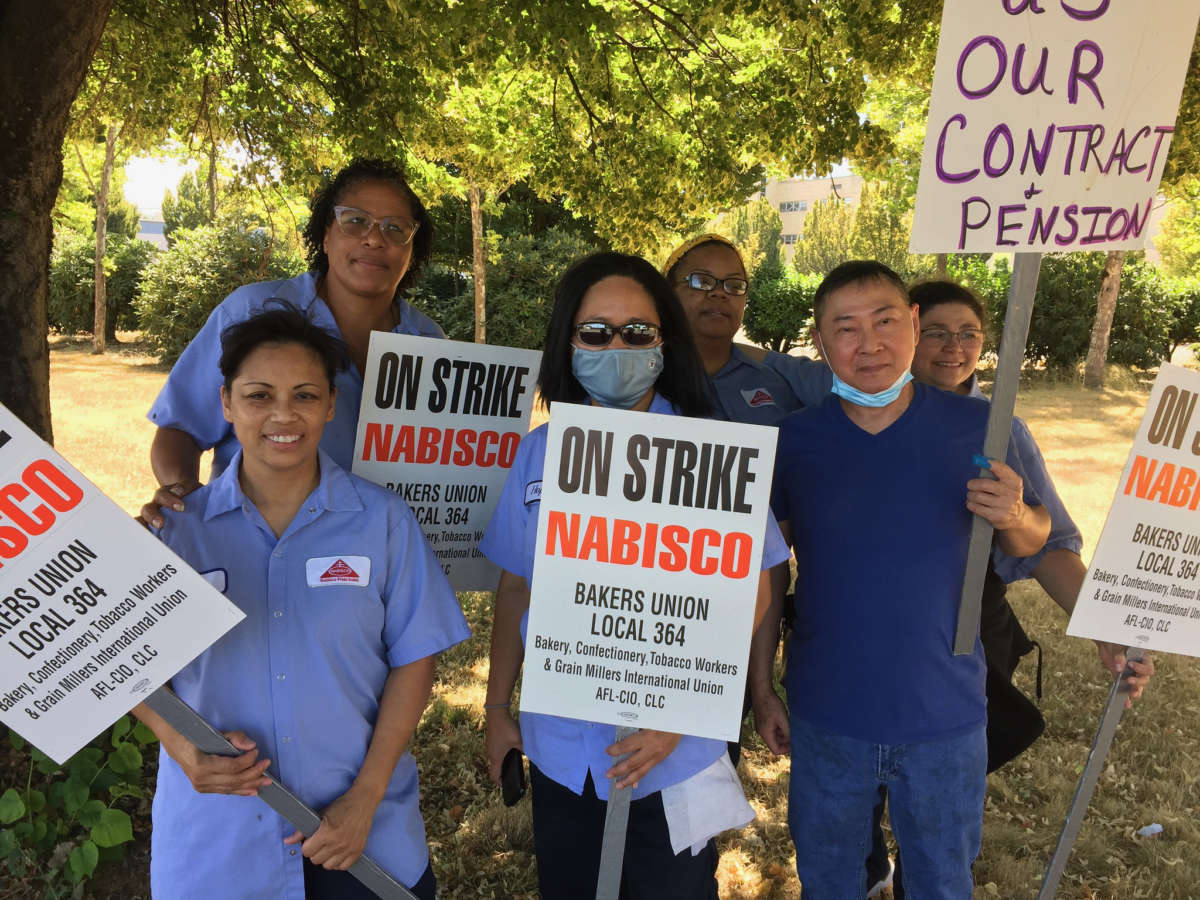

Confronted with management’s burdensome demands for contract concessions, Nabisco workers in Portland, Oregon, instigated a strike last month that has rapidly taken on national proportions. On August 10, around 200 members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM) Local 364 walked off the job at the industrial bakery. Since then, the workforces of every Nabisco production and distribution facility in the country have followed suit, a coordinated action years in the making. The strikers have drawn on the radical energies of a recently resurgent labor movement in the United States — a momentous upswell in a key vector of working-class power.

Sweet Deals for Executives, Scraps for Workers

Nabisco, the maker of popular processed foods like Chips Ahoy! cookies, Oreo cookies and Ritz crackers, is a subsidiary of Chicago’s Mondelēz International. When Kraft Foods split into different entities to skirt antitrust violations in 2012, its snack food business was spun off and reconstituted as Mondelēz, now a Fortune 500 company with $26 billion in yearly revenue. Mondelēz CEO Dirk Van de Put was compensated over $16 million in 2020; in 2017, he was lavished with a pay package of $42.4 million — 989 times the median pay of a Mondelēz employee. Meanwhile, management has declined to redistribute any of its pandemic profit gains; though people staying home in 2020 resulted in a major uptick in snack sales, the company has continued angling to cut overtime and healthcare benefits. Mondelēz’s single-minded focus on squeezing every possible cent from its workforce, combined with such exorbitant executive pay, has underscored disparities between workers and management, accelerating a discontentment that has been gathering strength for almost a decade.

Since Mondelēz assumed ownership of Nabisco in 2012, longtime workers claim, working conditions have deteriorated, sacrificed to management’s ever-more relentless drive for profits. In the background are ambient threats of outsourcing and job loss: The company halved its union workforce earlier this year, with plant closures in Fairlawn, New Jersey, and Atlanta, Georgia, and the union has had to negotiate with an acute awareness that the company can make good on its threats of offshoring. Six years ago, Mondelēz transferred Oreo production from Chicago to Mexico — a move that earned it condemnation from Trump, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders alike.

Against this background, tension between capital and labor within Mondelēz-Nabisco has heightened since contract negotiations in 2016, when management attempted to eliminate pensions in favor of 401(k)s. In April 2020, BCTGM ceded that ground — only for the company to return to the table with even more extensive demands. BCTGM Local 364 vice president and 14-year Nabisco veteran Mike Burlingham says Mondelēz has displayed no interest in compromise: “They don’t want to share their wealth with the workers.… They want to come to the table, insult us with their proposal — which is more like a list of demands — and try to tell us to our faces that this is for our own good,” he told Truthout.

The Mondelēz proposal, which a spokesperson euphemistically described as an “alternative work schedule,” would require more work for less pay, at an already taxing and physically demanding job. Burlingham says that even without the proposed changes, “a lot of us are already putting in 13 to 16 hours a day due to forced overtime, day in and day out, for weeks on end.”

The previous contract afforded workers time-and-a-half pay for shifts over 8 hours and Saturdays, with double time for Sundays. Now, the company wants to limit overtime pay to those who work more than 40 hours — without taking into account which days are worked, or the lengths of individual shifts. Burlingham estimated that for some workers, the reductions in overtime pay could result in losses of $10,000 per year.The past few years in the United States have seen a historic groundswell of labor actions, coinciding with the highest public favorability toward unions in decades.

The plan would also establish a two-tiered benefits system, under which new hires would also be charged more for health insurance — a well-worn tactic for stoking internal division within unions. This management overreach led to a breakdown in negotiations. It was Mondelēz-Nabisco’s continued intransigence that led BCTGM to trigger the Portland action, the first strike at the company in 52 years.

Coordinated by BCTGM International, the strike expanded to an interstate scale. Mondelēz has three factories (Chicago; Portland, Oregon; and Richmond, Virginia) and three distribution facilities (Aurora, Colorado; Addison, Illinois; and Norcross, Georgia) — all six of which are now on strike. These workforces were already stretched to breaking point. The frustrations expressed by strikers at the Portland bakery are far from isolated concerns, and were echoed by those at other Mondelēz facilities. Interviewed by Jacobin, utility operator April Flowers-Lewis, who has worked at the Chicago plant for 27 years, described deteriorating conditions: brutal schedules, rescinded benefits and an attitude of disrespect from management. In July, Mondelēz was also cited by the city of Chicago for failing to pay out sick leave.

A Mondelēz spokesperson, quoted by CBS, stated that the “alternative work schedule” proposals are intended to “promote the right behaviors” among workers. Elsewhere, the company described the goal of its proposal as “setting up our U.S. bakeries for future investment and long-term success.” At present, the company is busing in nonunion workers (colloquially, “scabs”) to continue production.

Meanwhile, as the action enters its third week in Portland, strikers have earned the resounding support of many in the community. Mohammed Mohammed, a production worker on the picket line, spoke to Truthout as a cacophony of celebratory honks from passing cars threatened to drown out his words: “I’m grateful for the city that’s shown us a lot of support. We got a lot of union support; a lot of local businesses bring us food.… People know we’re essential. We’re strong because of each other.”

Such expressions of solidarity have been plentiful, from supporters both on the ground and online (including Danny DeVito). A strike support GoFundMe has raised over $50,000, and BCTGM has urged a boycott of all of Nabisco’s enduringly popular snack foods. On the picket line, demonstrators have been joined by members of over a dozen other unions, including the AFL-CIO and UFCW. At one point, confirmed Mike Burlingham, union railroad conductors in Portland reversed their train and refused to cross the picket line to deliver their freight of confectionary ingredients to the bakery.

Strikers in Portland, as well as those in Atlanta, Richmond and Chicago, have received the aid of their local Democratic Socialists of America chapters. Portland DSA has helped coordinate solidarity rallies, marches and strike support, as has Portland Jobs with Justice, a labor and community activism coalition. Organizers entered a Fred Meyer grocery by the dozen to make shoppers aware of the boycott. Jobs with Justice co-chair Russell Lum told Truthout, “It’s a cry out to Nabisco, sure, but it’s also a cry out against a broken economic system…. The bleeding of these jobs [by outsourcing] is Mondelēz’s business model, and the signal to the workers is, ‘You’re next.’ That’s how Mondelēz wants to bargain, with the workers feeling like they’re on a knife’s edge.”

Demanding More Than Crumbs

The past few years in the United States have seen a historic groundswell of labor actions, coinciding with the highest public favorability toward unions in decades. 2018-2019 were particularly militant years; notable developments include the late 2019 major strike at GM and the Red for Ed wave of nationwide teachers’ strikes. Strike activity reached a 30-year-high in 2019. Some Bureau of Labor Statistics data gave the impression that work stoppages dropped off precipitously at the outset of the COVID-19 crisis — though, it’s worth noting that these numbers do not reflect actions involving under 1,000 employees. During that period, amid complicating factors like layoffs and social distancing, there was an enormous number of small-scale pandemic-safety walkouts by essential workers. Alternate data better captured these stochastic, nontraditional actions. In other words, solidarity, organizing and radical energies persisted throughout the pandemic. And though the virus is still exacting a devastating toll, the return to major strike activity in 2021 indicates a potential for sustained worker militancy.

BCTGM’s modest size makes its members’ boldness all the more impressive. Amid a national climate hostile to unions, BCTGM, further beleaguered by offshoring and plant closures, fell from over 114,000 members in 2002 to about 63,900 in 2019 — making it one of the smallest production worker unions. Historically, the union has not been particularly militant. Like many manufacturing strikes, BCTGM’s actions have tended towards the defensive: protecting existing wins, rather than breaching new territory.BCTGM’s bold actions of the summer of 2021 are an indicator that unions in the United States, resurgent to a degree unseen in decades, will sustain their struggle into the future.

That said, “there are a lot of signs that even manufacturing union workers are increasingly fed up with employer demands for concessions,” says C.M. Lewis, an editor at the labor publication Strikewave. The Mondelēz-Nabisco strikes are preventative measures: “We’re not on strike to secure huge gains. We’re on strike to keep what we’ve already got,” Cameron Taylor, BCTGM Local 364’s business agent, told HuffPost. However, taken with a string of recent BCTGM actions, they’re a component of a positive trend. Says Lewis, “That Nabisco workers [are] striking in multiple states is rare and encouraging, and could be a sign of increased militancy down the road.”

BCTGM members are finding their footing: They organized a workforce of several hundred at a Tennessee brewery in December 2020. And in July, BCTGM members took on the titanic PepsiCo, striking at a plant owned by its subsidiary Frito-Lay in Topeka, Kansas, over concerns analogous to those at Nabisco. The 19-day strike ended with a renegotiated contract — which didn’t meet every BCTGM term, but still held ground and won some gains. Though short of unmitigated victory, that strike still helped bolster the confidence of Nabisco workers in Portland, as Mike Burlingham related to Truthout: “There was a show of solidarity” with Frito-Lay employees, he said, and “it was really good to see those workers were able to come to an agreement … and were successful.” Burlingham added, “There’s been an influx of strikes around the country … people are paying attention to what’s going on. It’s getting to a point where people are saying, ‘It’s enough of the corporate greed. Enough is enough.’”

BCTGM is up against a company that has proven willing to go to great lengths to further exploit workers and ensure the flow of profit. Mondelēz’s threats of offshoring have weight behind them, thanks to free trade agreements and loosened restraints on capital mobility. Mondelēz also maintains massive production capability at a “superplant” in Mexico — ostensibly, the “world’s largest cookie plant” — giving the company enormous leverage in its threats to shift production to workforces in Mexico that are even more callously exploited. (Relatedly, the company, along with Nestle, Cargill, Hershey, and others, has also been named in a class action lawsuit alleging that it “knowingly” utilized forced child labor. That’s far from its only scandal.)

With corporate power further entrenched by the depredations of neoliberal policy and the dismantling of labor laws, workers often find themselves struggling to preserve a status quo. Yet, as C.M. Lewis says, “Successful strikes build confidence and power, and Nabisco workers are experiencing firsthand what potential power they hold in their workplaces. Although this is a defensive strike for the moment, holding the line now is a good start toward going on the offensive and raising standards instead of managing declining working conditions.”

Unions across the country are demonstrating a greater willingness to strike when companies go beyond the pale. The Nabisco picketers all shared that sense of last-straw frustration. Said Oreo production line worker Nicole Bertholomey, “They’re being greedy. We work so hard for this company, and we have families at home. They’re making so much money, and they still want to take everything away from us.”

The 2021 Nabisco strike sits at the intersection of two intertwined forces: growing union confidence, support and strike activity, in correlation with widespread austerity and egregious demands from the ownership class. The interests of capital, at Mondelēz and elsewhere, are not only unwilling but are structurally unable to pursue any end but endless profit. As Nabisco employee Mohammed Mohammed told Truthout, echoing his coworker Mike Burlingham, “It came to a point where enough is enough.”

That phrase could be heard from many others up and down the Nabisco picket line, and the sentiment has lately found purchase throughout the country, from coal mines to the offices of The New Yorker. “Labor” is not a monolithic entity, and there are of course complex challenges impacting unions’ ability to take on corporate power. Still, it’s evident that workers are increasingly unwilling to capitulate — and less hesitant to deploy the strike.

Hope lies in the fact that an embattled populace has, in recent years, been reminded again and again that organizing is the real vehicle of working-class power. BCTGM’s bold actions of the summer of 2021 are an indicator that unions in the United States, resurgent to a degree unseen in decades, will sustain their struggle into the future.

Nabisco strike in Portland spread to other cities

by: KOIN 6 News Staff Posted: Sep 4, 2021 /

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Portland City Commissioners Jo Ann Hardesty and Carmen Rubio joined the picket line outside the Nabisco bakery facility in Northeast Portland on Saturday.

They rallied with workers in front of the bakery as passing cars honked their support. Nabisco bakery workers have been on strike for nearly a month and their action has now spread to Nabisco facilities in Denver, Chicago, Atlanta and elsewhere.

“I know the sacrifice you make, I know what it’s costing your family,” Hardesty told the striking workers. “This is happening all across the country because of you.”

Nabisco’s corporate parent, Mondelez International, posted a new contract offer to the workers on their website. The offer, made Thursday, offers a $5000 ratification bonus, a 60-cent-per-hour raise and a 401K match increase, among other items.

Mondelez said the offer expires September 7.

No more buttery Ritz Crackers until some negotiation happens

SEPTEMBER 2, 2021

Thanks to a heated labor battle, the Triscuit supply could run drier than the actual cracker. Grocery stores are stocking up on Nabisco treats because of a production slowdown at bakeries and distribution facilities around the country.

Why is production slowing down? On August 10, about 200 employees at a Nabisco bakery in Oregon put down whatever makes Ritz crackers so buttery and went on strike. Since then, workers in four other states have joined them.

What do they want? Workers want their pensions back after the company switched to a 401(k) plan in 2018. They’re also angry about a July proposal from Mondelez International, Nabisco’s parent company, that would increase shift length but cut overtime pay.

Employees have also expressed concerns about the company’s outsourcing of work to Mexico after two recent factory closures in the US.

Mondelez has denied those claims and said that, while it is moving some workers to 12-hour shifts to handle the recent spike in demand, employees are well compensated.

Zoom out: Workers have been gaining leverage in a labor market where qualified employees are hard to find. This Nabisco standoff will test the limits of that resurgent power. – MM

Alexis Christoforous

·Anchor

Wed, September 1, 2021,

Steven James has been working as a machine operator making Oreos, Chips Ahoy! and other Nabisco snacks at a plant in Richmond, Va. for 20 years.

On Aug. 16, James joined about 1,000 of his fellow union members in five states and walked off the job to protest what they say are “unfair” demands for concessions in contract negotiations with Nabisco's parent company Mondelez International (MDLZ). James, who isn't working another job, said he plans to stay out of the plant until a fair contract is signed.

“We're not asking for a lot,” James told Yahoo Finance Live. “We just want a fair contract.”

As America’s appetite for snack foods has grown during the pandemic, James said he and his colleagues on the frontlines have been working 12-hour shifts, seven days a week.

“It was just constant. Never had time to spend with the kids. Never had time to spend with the family,” he said.

The walkout began on Aug. 10 at a biscuit bakery in Portland, Ore., and has since spread to Aurora, Colo., Richmond, Va., Chicago, Addison, Illinois, and Norcross, Ga. Union members in those states have been working without a contract since May and are represented by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM).

James said he was given one-time “hazard pay” of $300 earlier this year for working long hours during the pandemic while “some of the supervisors, they got $10,000."

"We had some management working from home. So, of course they were good, they were safe. We risk our lives coming out every day working all those hours,” he added.

The strike has not affected Nabisco’s ability to churn out popular snacks during the pandemic, since Mondelez International has been using non-union workers at plants where there have been walkouts.

James said he and his union members are asking customers to show their support by boycotting the snack giant.

“We try to tell everyone, do not buy any Nabisco products at this time, because we are on strike,” said. James. “The community has really shown us some support. We have businesses and our local brothers and sisters have really been giving us a lot of support, and they are with us walking on the line as well.”

Union workers are asking customers to boycott Nabisco snacks like Ritz Crackers. Credit: Mondelez International

In a statement, Mondelez said, “Our goal has been — and continues to be — to bargain in good faith with the BCTGM leadership… while also taking steps to modernize some contract aspects which were written several decades ago.”

'Keep our jobs here in the U.S.'

Union workers also want Mondelez to restore their pensions, which were replaced by a 401(k) plan in 2018.

Striking workers are also protesting two factory closures in February in Atlanta, Georgia and Fair Lawn, New Jersey, a move the union says is part of a larger plan to transfer low-wage jobs to Mexico.

“They closed two of our plants and they sent the product to Mexico,” said James. “We just want to keep our jobs here in the U.S.”

In a statement, BCTGM International President Anthony Shelton said union workers “are telling Nabisco to put an end to the outsourcing of jobs to Mexico and get off the ridiculous demand for contract concessions at a time when the company is making record profits.”

Mondelez International’s net income climbed 98% in the quarter ended in June to $1.1 billion, while sales climbed 12.4% to $6.6 billion, compared to the same time a year ago.

Mondelez denies that any jobs went to Mexico as a result of the recent factory shutdowns in Georgia and New Jersey. Company spokeswoman Laurie Guzzinati told Yahoo Finance that production at the shuttered facilities has been absorbed by existing bakeries in Portland and Richmond. Some Oreo production was shifted to Mexico in 2016, a move that Donald Trump criticized as a presidential candidate.