Massive new animal species discovered in half-billion-year-old Burgess Shale

Palaeontologists at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) have uncovered the remains of a huge new fossil species belonging to an extinct animal group in half-a-billion-year-old Cambrian rocks from Kootenay National Park in the Canadian Rockies. The findings were announced on September 8, 2021, in a study published in Royal Society Open Science.

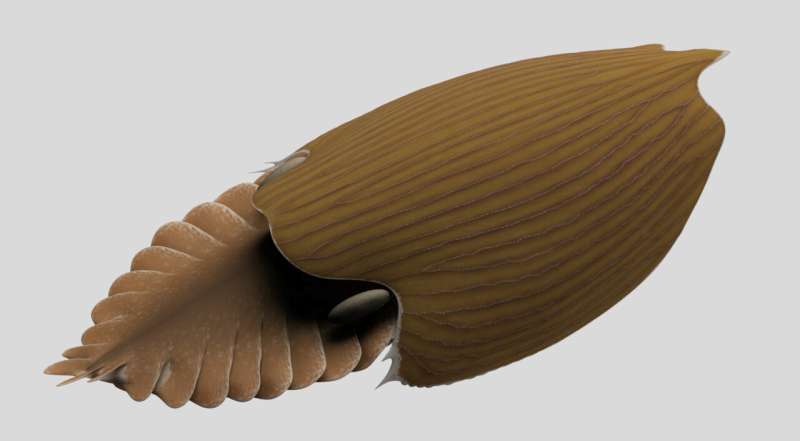

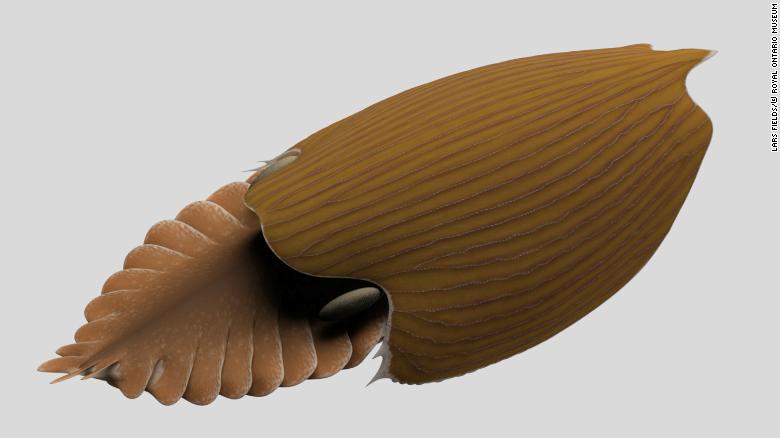

Named Titanokorys gainesi, this new species is remarkable for its size. With an estimated total length of half a meter, Titanokorys was a giant compared to most animals that lived in the seas at that time, most of which barely reached the size of a pinky finger.

"The sheer size of this animal is absolutely mind-boggling, this is one of the biggest animals from the Cambrian period ever found," says Jean-Bernard Caron, ROM's Richard M. Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology.

Evolutionarily speaking, Titanokorys belongs to a group of primitive arthropods called radiodonts. The most iconic representative of this group is the streamlined predator Anomalocaris, which may itself have approached a meter in length. Like all radiodonts, Titanokorys had multifaceted eyes, a pineapple slice-shaped, tooth-lined mouth, a pair of spiny claws below its head to capture prey and a body with a series of flaps for swimming. Within this group, some species also possessed large, conspicuous head carapaces, with Titanokorys being one of the largest ever known.

"Titanokorys is part of a subgroup of radiodonts, called hurdiids, characterized by an incredibly long head covered by a three-part carapace that took on myriad shapes. The head is so long relative to the body that these animals are really little more than swimming heads," added Joe Moysiuk, co-author of the study, and a ROM-based Ph.D. student in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto.

Why some radiodonts evolved such a bewildering array of head carapace shapes and sizes is still poorly understood and was likely driven by a variety of factors, but the broad flattened carapace form in Titanokorys suggests this species was adapted to life near the seafloor.

"These enigmatic animals certainly had a big impact on Cambrian seafloor ecosystems. Their limbs at the front looked like multiple stacked rakes and would have been very efficient at bringing anything they captured in their tiny spines towards the mouth. The huge dorsal carapace might have functioned like a plough," added Dr. Caron, who is also an Associate Professor in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Earth Sciences at the University of Toronto, and Moysiuk's Ph.D. advisor.

All fossils in this study were collected around Marble Canyon in northern Kootenay National Park by successive ROM expeditions. Discovered less than a decade ago, this area has yielded a great variety of Burgess Shale animals dating back to the Cambrian period, including a smaller, more abundant relative of Titanokorys named Cambroraster falcatus in reference to its Millennium Falcon-shaped head carapace. According to the authors, the two species might have competed for similar bottom-dwelling prey.

The Burgess Shale fossil sites are located within Yoho and Kootenay National Parks and are managed by Parks Canada. Parks Canada is proud to work with leading scientific researchers to expand knowledge and understanding of this key period of earth history and to share these sites with the world through award-winning guided hikes. The Burgess Shale was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 due to its outstanding universal value and is now part of the larger Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.

The discovery of Titanokorys gainesi was profiled in the CBC's The Nature of Things episode "First Animals." These and other Burgess Shale specimens will be showcased in a new gallery at ROM, the Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, opening in December 2021.

Giant 'swimming head' creature lived in our oceans 500 million years ago

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

Updated Wed September 8, 2021

Photos: Ancient finds

This illustration shows the primitive arthropod Titanokorys gainesi from the front. This creature lived along the ocean floor half a billion years ago

Radiodonts, a group of primitive arthropods, were widespread after the Cambrian explosion event 541 million years ago -- a time when a multitude of organisms suddenly appeared on Earth, based on the fossil record.

The newly discovered fossil belonged to Titanokorys gainesi, a radiodont that reached 1.6 feet (half a meter) in length -- which was huge, compared to other ocean creatures that were about the size of a pinkie finger.

The fossil was found in Cambrian rocks from the Kootenay National Park, located in the Canadian Rockies. A study detailing the fossil published Wednesday in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

New find shows animal life may have existed millions of years before previously thought

"The sheer size of this animal is absolutely mind-boggling, this is one of the biggest animals from the Cambrian period ever found," said study author Jean-Bernard Caron, the Royal Ontario Museum's Richard M. Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology, in a statement.

Titanokorys would have been a bewildering animal to encounter. It had multifaceted eyes, a mouth shaped like a pineapple slice that was lined in teeth, and spiny claws located beneath its head to catch prey. The animal's body was equipped with a series of flaps that helped it swim. And Titanokorys had a large head carapace, or a defensive covering, like the shell of a crab or turtle.

This is an artist's illustration reconstructing Titanokorys gainesi as it appeared in life.

"Titanokorys is part of a subgroup of radiodonts, called hurdiids, characterized by an incredibly long head covered by a three-part carapace that took on myriad shapes. The head is so long relative to the body that these animals are really little more than swimming heads," said study coauthor Joe Moysiuk, a Royal Ontario Museum-based doctoral student of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, in a statement.

A 550-million-year-old worm was one of the first animals to move and make decisions, a new study says

Researchers are still trying to understand why some radiodonts had such a variety of head carapaces, which came in all shapes and sizes. It's unclear what this head gear was protecting them from, given their size compared to other sea life at the time. In the case of Titanokorys, the broad, flat carapace suggests it had adapted to live near the seafloor.

"These enigmatic animals certainly had a big impact on Cambrian seafloor ecosystems. Their limbs at the front looked like multiple stacked rakes and would have been very efficient at bringing anything they captured in their tiny spines towards the mouth. The huge dorsal carapace might have functioned like a plough," Caron said.

The carapace of T. gainesi (lower), along with two symmetrical rigid plates (upper), covered the head from the underside. They formed a three-part set of armor that protected the head on all sides.

The fossils of Titanokorys were found in Marble Canyon, located in northern Kootenay National Park, which has been the site of many discoveries of Cambrian fossils dating back 508 million years ago. The site is part of the Burgess Shale, a deposit of well-preserved fossils in the Canadian Rockies. The Burgess Shale is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

One of those discoveries includes the radiodont Cambroraster falcatus, so named because its head carapace is similar in shape to the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars. It's possible that these two species scuffled on the bottom of the sea for prey.

Titanokorys, and other fossils collected from Burgess Shale, will be displayed in a new gallery at the Royal Ontario Museum beginning in December.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/6XABLTE5QBHYDERPLCEGZCXEKI.jpg)