By Vasanthie Maharaj, Franciska Lake, Jessica Edwards, Matthew Law

PUBLICATION INFO

Author(s): Vasanthie Maharaj, Franciska Lake, Jessica Edwards, Matthew Law

Date: July, 2021

First Presented: GISTM series - Focus on Social

Type: Article

It's probably not by chance that the first principle of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) to “respect the rights of project-affected people” and to “meaningfully engage them at all phases of the tailings facility lifecycle”. This social focus reflects not only the potential vulnerability of communities close to tailings storage facilities (TSFs), but also aligns with the broader trend to integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into tailings management.

While social engagement with project-affected people is a well-established practice in various permitting, licensing and authorisation processes, the GISTM requires engagement that endures for the operational life of the tailings facility and into closure – which in turn implies the need for a social engagement plan for the lifetime of the mine and beyond. Such engagement should extend to all stakeholders, including regulators, local government, traditional authorities, landowners, community-based organisations, local communities and the broader public.

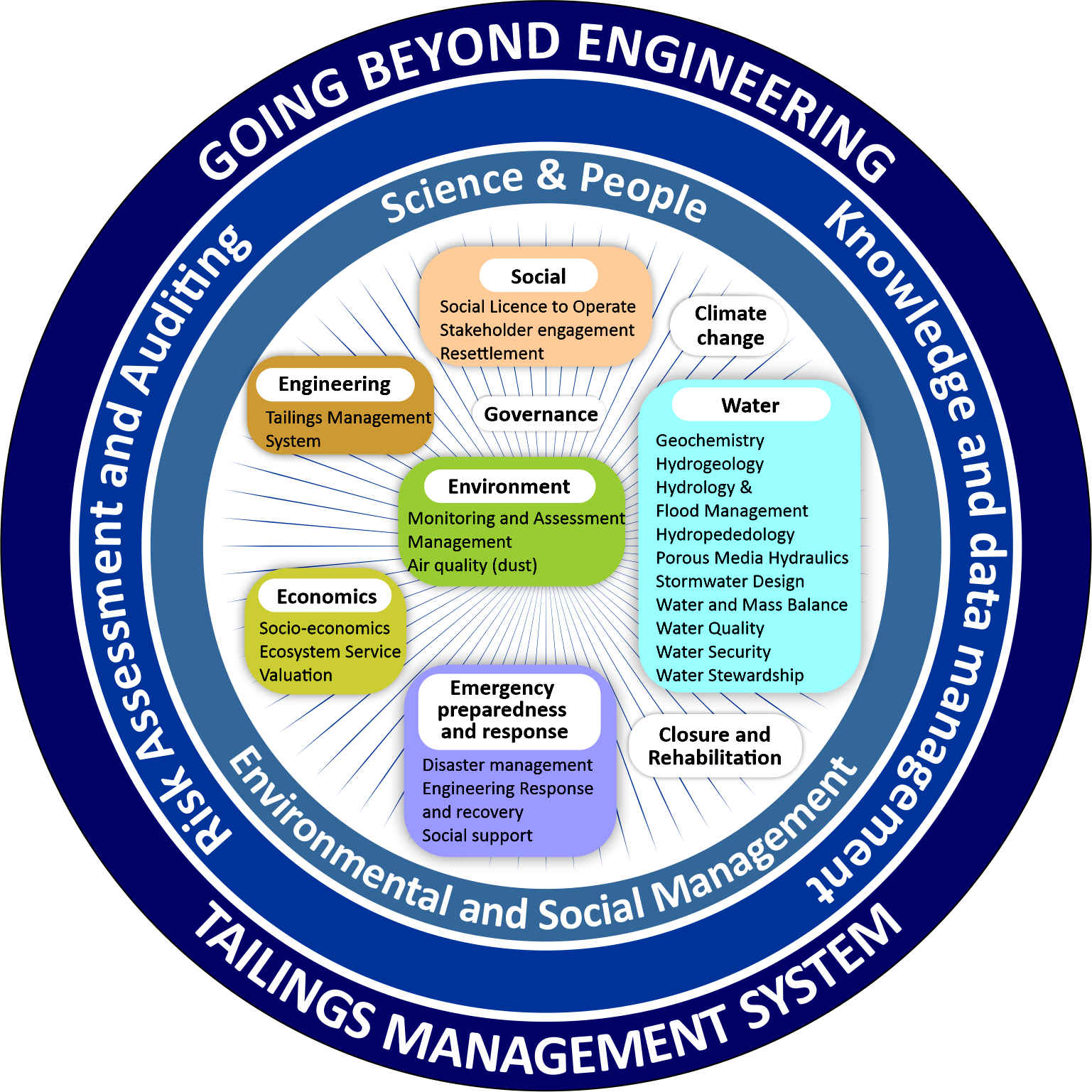

This engagement needs to form part of the mine’s Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS), which the GISTM in turn requires to be incorporated into – or to at least inform – the Tailings Management System (TMS). This presents one of the initial transitions that mining operations will have to make to comply with the GISTM and to ensure that on-site responsibilities are aligned, collaboration is fostered and the two sub-systems of an ESMS – the social and the environmental – are integrated with engineering aspects on site.

Integration of engineering, socio-economic and environmental aspects will require the coalescence of data and skills sharing between these spheres. In this way engineers will be better equipped to understand and anticipate socio-economic risks, and to disseminate information in a stakeholder-friendly format, to build trust and respect between mine operations and stakeholders.

One underlying concern that is key to TSF-related social engagement is the potential for, and implications of, catastrophic failure. It is critical for mining operations to understand community dynamics in order to prepare effective emergency response and recovery plans for these eventualities. This is just one example which social engagement can assist to address. Others include the identification of risk factors, planning for spatial or economic displacement, social vulnerability, resettlement and compensation, and livelihood restoration.

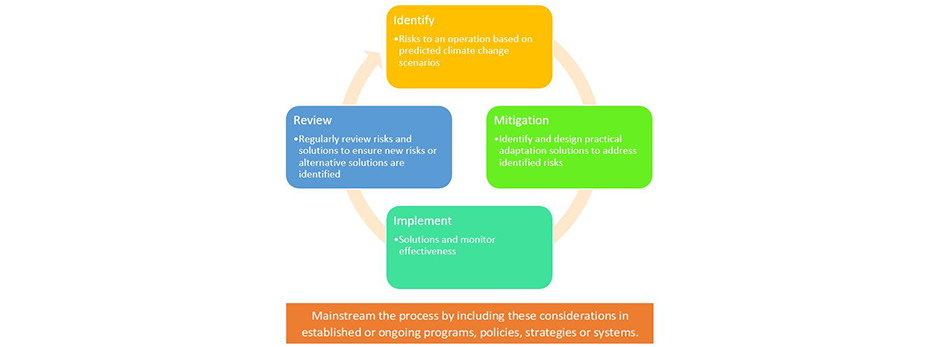

Aligning with GISTM requirements will include ongoing surveillance programmes that identify changes in social systems and valuable ecosystem services to communities. As part of impact identification and mitigation, there is also a need to establish direct mechanisms for stakeholders to share their unique knowledge and understanding of the area. Social engagement related to TSF management needs to build trust and stakeholder capacity, demonstrating a respect for human rights that informs management decisions throughout the TSF lifecycle.

PUBLICATION INFO

Author(s): James Morris , Franciska Lake, Jacky Burke

Date: July, 2021

First Presented: GISTM series - Focus on Specialists

Type: Article

With the release of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) in August 2020, the foundation of this field has shifted, and the stakes have been raised. The standard sets a new bar for corporate responsibility and opens the door for significant improvement in performance. Among its demands is that mines engage with multiple spheres of influence when designing and managing tailings storage facilities (TSFs).

Once the exclusive domain of geotechnical, civil and water engineers, TSF management now involves a complex array of requirements and stakeholders – which the GISTM seeks to address. As the mining sector comes to terms with the implications of this standard, it is also clear that a TSF is no longer considered a temporary operational structure; rather, it must endure safely for centuries.

Over the years, TSF management has included the sciences of water, soil, bedrock and geohydrology, as well as the geological and seismic setting. It also deals with environmental issues such as stormwater and air quality, as well as long-term sustainability and governance. The field also accommodates the local and regional setting, including communities and regulators. Financial institutions and investors have recently weighed in on questions of safety and risk.

The GISTM embraces all these spheres, so achieving the requirements of this standard will require a comprehensive range of disciplines and skill-sets. The standard itself recognises this, especially in its discussion of the Integrated Knowledge Base – one of six topic areas which is outlined alongside Affected Communities; Design, Construction, Operation and Monitoring of the Tailings Facility; Management and Governance; Emergency Response and Long-Term Recovery; and Public Disclosure and Access to Information.

The TSF design and management remain key technical elements in the GISTM, which highlights the range of expertise, knowledge and data required for site characterisation. Generating this data requires geomorphologists, geologists, geochemists, hydrologists and hydrogeologists – not to mention civil and geotechnical engineers and experts in seismicity. With the detailed input from each of these disciplines, the necessary breach analysis required by the GISTM can be developed. This would consider failure modes, site conditions and slurry properties – in some cases predicting the consequences of failure.

The GISTM is essentially a high-level statement of intent – the ‘why’ and ‘what’ which precedes the more detailed guidelines and regulations. TSF owners’ in-house standards and procedures, as well as the recently released guidance and conformance protocols from the SAIMM, will define the ‘how’.

Having the necessary knowledge and data to safely build and manage a TSF is one challenge; using that knowledge effectively is another. The GISTM therefore points out that mines must use all elements of their knowledge base – “social, environmental, local economic and technical” – to inform their timeous decision making through the life-cycle of the TSF. There is also the role of emergency response and humanitarian aid to consider. This often demands a level of information sharing and operational integration that many mines simply have not yet achieved.

In many cases, the information that mines need is already available on site, although new systems of monitoring and analysis may also be required; the technology to do this is readily accessible, as is the expertise. Often, however, a paradigm shift is needed to overcome internal 'silo' thinking.

SRK Consulting has been involved in TSF design and management for decades, and has also been a pioneer in supporting clients with innovative solutions to their environmental and social impacts. Our teams embrace diverse disciplines and skill-sets, and have evolved the kind of multi-disciplinary approach and experience demanded by the GISTM.

SRK Consulting’s multi-disciplinary approach and capability positions it well to help mining companies to align their TSF practice with the requirements of the GISTM. Our experience covers a range of disciplines and sub-disciplines relevant to the new standard, from engineering and water management to ESG and disaster management. With our integrated approach, we ensure that inter-disciplinary teams work closely and effectively for optimal results.