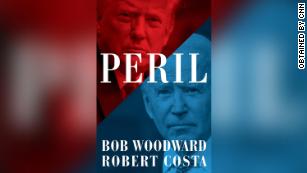

Eos presents an essay from the recently published book 'Womansplaining'

Updated 12 Sep, 2021

DAWN.COM

LONG READ

With the Taliban take-over of Afghanistan leading to concern about the status of women’s freedoms in that country, as well as the birth of a vocal women’s resistance there, it is perhaps instructive to look back at Pakistan’s trajectory in terms of its own women’s movement and where it stands today. Eos presents one of 21 essays by women activists from the recently published book Womansplaining, excerpted with permission

Movements, meaning an organised group of people pursuing a shared agenda for change through collective action with some continuity over time, arise at particular historical junctures. The specific circumstances and configurations of power confronted, particularly the character of the state, but also market forces and the dynamics of national and international politics in which movements emerge and play out, are as important in shaping a movement as the ideals, volition, actions, identity and resources of its activists.

The confluence of these factors determines the issues a movement takes up, its goals and modalities and the outcome. To survive, movements must be sufficiently agile to respond and adjust to changing circumstances and opportunities, sometimes taking on new incarnations. The celebrated era of the Pakistani women’s movement of the 1980s, therefore, can only be properly understood from the perspective of its context; the brutal and brutalising martial law and quasi-military rule of General Ziaul Haq from 1977 to 1988.

Many of the women who helped steer the activism of the 1980s, and those who joined the movement in the 1990s, are still actively struggling for gender equality today. But whether women’s contemporary activism is a continuation of that movement is a moot question, given the emergence of new activists as well as new forms and priorities of activism.

In many ways, it is also a less important question than whether a women’s movement exists today and how vibrant the movement is.

DEFYING THE MILITARY TO SAFEGUARD WOMEN’S RIGHTS

With the Taliban take-over of Afghanistan leading to concern about the status of women’s freedoms in that country, as well as the birth of a vocal women’s resistance there, it is perhaps instructive to look back at Pakistan’s trajectory in terms of its own women’s movement and where it stands today. Eos presents one of 21 essays by women activists from the recently published book Womansplaining, excerpted with permission

Movements, meaning an organised group of people pursuing a shared agenda for change through collective action with some continuity over time, arise at particular historical junctures. The specific circumstances and configurations of power confronted, particularly the character of the state, but also market forces and the dynamics of national and international politics in which movements emerge and play out, are as important in shaping a movement as the ideals, volition, actions, identity and resources of its activists.

The confluence of these factors determines the issues a movement takes up, its goals and modalities and the outcome. To survive, movements must be sufficiently agile to respond and adjust to changing circumstances and opportunities, sometimes taking on new incarnations. The celebrated era of the Pakistani women’s movement of the 1980s, therefore, can only be properly understood from the perspective of its context; the brutal and brutalising martial law and quasi-military rule of General Ziaul Haq from 1977 to 1988.

Many of the women who helped steer the activism of the 1980s, and those who joined the movement in the 1990s, are still actively struggling for gender equality today. But whether women’s contemporary activism is a continuation of that movement is a moot question, given the emergence of new activists as well as new forms and priorities of activism.

In many ways, it is also a less important question than whether a women’s movement exists today and how vibrant the movement is.

DEFYING THE MILITARY TO SAFEGUARD WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Illustration by Radia Durra

The contemporary women’s rights movement burst on to the scene in 1981, several years into the country’s most oppressive military dictatorship. Political parties were banned; politicians, trade unions and anyone who dared to oppose the regime ferociously suppressed; fundamental rights suspended; public hangings and floggings commonplace. For women, the challenge was the military’s “arrogat[ing] to itself the task of ‘Islamising’ the country’s institutions in their entirety” (Omar Asghar Khan, 1985).

As the least powerful group, women were easy targets and a way for the regime to demonstrate its ‘Islamic’ credentials. In a rigidly patriarchal society, there was no popular resistance to the almost casual rescinding of women’s rights. Women themselves did not respond in an organised manner until September 1981.

Igniting action was a small news item tucked away on an inside page, noticed by a Karachi-based women’s collective, the Shirkat Gah-Women’s Resource Centre. The news item reported that a woman (Fehmida) and a man (Allah Bux) had been sentenced respectively to 100 lashes and stoning to death under the soon-to-be-infamous Hudood Ordinances.

The promulgation of these ordinances in February 1979 had gone largely unnoticed during the trial of the ousted Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was hanged in April 1979. Shocked and bewildered by how such sentences could be legal, the collective decided it was time to act.

Given their limited numbers and the adverse circumstances, the single-most remarkable achievement of this entirely indigenous and unfunded movement was that it placed women and their rights squarely and permanently on the national agenda.

With only nine members, Shirkat Gah reached out to both women and men, urging collective action to prevent the sentences from being carried out. It was the diametrically opposed responses of women and men that galvanised the women’s movement. Men were either dismissive, believing such punishments would never be carried out in Pakistan, or defeatist, saying that individual citizens were helpless under martial law.

For women, these sentences represented the last straw. They were already angered by the regime’s numerous initiatives to curtail women’s rights, by the spiralling misogyny unleashed under the pretext of being more Islamic by people encouraged by state rhetoric, by the unprecedented harassment of women in public spaces, including women previously shielded by class privilege. Palpable anger and outrage at the meetings called by Shirkat Gah led to the formation of the Khawateen Mahaz-i-Amal, better known by its English name, the Women’s Action Forum (WAF). WAF chapters opened in quick succession in Lahore, Islamabad and Peshawar and, for a short while, in Abbottabad.

Led by WAF, the women’s movement mounted the most vociferous opposition to ‘Islamisation’ until Zia’s death in 1988. The relentless onslaught of legal and policy measures and proposals to curtail women’s rights demanded ceaseless activism. These included written and unwritten directives imposing ‘Islamic’ dress codes for a widening circle of women, barring female athletes from competitions, preventing women in the foreign ministry from serving abroad, imposing a moratorium on the recruitment and promotion of women in banks, an ‘anti-obscenity’ campaign seeking to eliminate women’s images from advertisements and in all media, and the Ansari Commission’s recommendations to seriously curtail women’s political participation.

Reducing the legal status of all women and non-Muslim men to half that of Muslim men started with the Hudood Ordinances, continued with the proposed ‘Law of Evidence’ and culminated in the proposed qisas and diyat law stipulating this ‘half-human’ status in black and white.

In the 1980s, women’s activism was reactive, state-focused and adversarial. The movement was led largely by middle- and upper-class working women who, having gained the most in their personal lives, stood to lose the most. But they were also better placed to face the risks of activism under martial law. Few of the new legal measures were likely to directly impact the personal lives of these activists. The fear was of a tsunami-like impact that the reducing of women’s legal rights, their further marginalisation and their exclusion from all decision-making positions would bring.

Numerous women’s organisations were involved but WAF provided the underlying coordination and strategic direction, becoming the face of the movement, a role facilitated by its policy of not accepting any funding other than personal donations and its principle of collective leadership that refused to acknowledge individual leaders, especially in the press.

With only a few hundred activists, the movement relied heavily on disrupting public spaces with street protests despite martial law prohibitions on public gatherings, to leverage attention, and on a supportive print media made more responsive given the ban on reporting political news, to amplify its message.

As a platform for individual women and women’s organisations, WAF initially adopted a minimal agenda for maximum buy-in, mobilising many women with no prior experience of, or inclination for, activism. Given the ban on politics, WAF deliberately called itself non-political. It reclassified itself as non-aligned and secular in 1991 and dropped the strategic use of Islam to counter laws proposed in the name of religion. A significant number of its activists were associated with progressive movements and participated in pro-democracy events, carefully explaining that this was in their individual capacity, not as WAF members — a distinction often lost on the press and on others.

With only a few hundred activists, the movement relied heavily on disrupting public spaces with street protests despite martial law prohibitions on public gatherings, to leverage attention, and on a supportive print media made more responsive given the ban on reporting political news, to amplify its message. Women’s defiance under martial law ensured public attention and media appreciation and earned the respect of politicians and other politically engaged actors.

Activists consciously engaged trade unions and political parties. Individual activists knew feminists and women’s groups abroad, but these links were irrelevant during this period, as the movement ignored international events and processes, including the 1985 UN World Conference on Women.

Given their limited numbers and the adverse circumstances, the single-most remarkable achievement of this entirely indigenous and unfunded movement was that it placed women and their rights squarely and permanently on the national agenda so that, for example, all political parties, including the conservative politico-religious Jamaat-i-Islami, started addressing women in their agendas. Other achievements included several discriminatory proposals curtailing women’s rights being abandoned, such as the Ansari Commission recommendations and a misogynist preacher’s programme on state-controlled television being discontinued.

The new discriminatory laws of evidence, and the qisas and diyat provisions in the law, could not be stopped but were delayed for years and enacted minus some of the most blatantly discriminatory aspects. Yet the Hudood Ordinances, having overturned the principle of presumed innocence, continued to fill the jails with women accused by former husbands, vindictive neighbours and random strangers, until the Women’s Protection Act of 2006; and the deep-seated changes wrought by Zia to the state and society continue to plague the country to this day. The current status of women’s activism has to be understood in the light of changes that occurred in the following two decades.

THE TRANSFORMATIVE DECADES

Zia’s death and the return of democracy in 1988 brought a major shift in the context and content of activism. The sense of urgency dissipated, political differences submerged in the struggle against a military dictator surfaced and activists returned to careers put on hold for almost a decade, reducing the number of proactive women.

Modalities changed: the skills of adversarial politics developed under martial law gave way to critically engaging authorities in less confrontational ways. Street protests became less frequent. New avenues for influencing were explored, facilitated by the links forged with politicians, and the fact that a significant number of women activists joined mainstream politics.

Several notable developments impacted the movement. Freed from incessantly countering anti-women moves, activists started defining their own agenda, demanding more rights and improved policies across a broad range of issues in addition to the rescinding of the zina laws and other regressive measures introduced by Zia.

The movement’s identity became more diffused. WAF ceased to be the movement’s singular face, although it still spearheaded some initiatives, for example, preventing the privatisation of the First Women Bank through a writ petition in court. Movement-linked women’s organisations took up issues for which they had no time under Zia, having understood how easily de jure rights can be overturned when so few women know about, much less enjoy, their rights.

Movement-linked women’s organisations took up issues for which they had no time under Zia, having understood how easily de jure rights can be overturned when so few women know about, much less enjoy, their rights.

Individual women’s organisations led initiatives on diverse issues such as political rights, education, health, workers’ rights, development policies and the need for a permanent commission on women to serve as a watchdog body. Media visibility waned as politics reclaimed centre stage. The movement reached fewer people as coverage was consigned to city pages, if carried at all.

During the unstable democracy of the 1990s, activists’ relationship with the state “vacillated between co-operation and collaboration with Benazir Bhutto [1988–90, 1993–96], and confrontation and contestation during the time of Nawaz Sharif [1990–93, 1997–99]” (Rubina Saigol, 2016). Threats to women’s rights became embedded in wider governance issues, such as the proposed Shariat Bill.

WAF mobilised a broader coalition with other human rights groups and religious minorities, subsequently formalised as the Joint Action Committee for People’s Rights, which started to articulate positions on many issues. An unintended consequence was the reduced visibility of women’s distinct voices.

A decade of extensive networking both within and outside the country replaced the inward-looking isolation under Zia, spurred in particular by the United Nations conferences on human rights (1993), population and development (1994) and, especially, the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (FWCW).

WAF engaged in the 1990s conferences, preparing position papers that were circulated to and by organisations and individuals from Pakistan and elsewhere, although WAF’s no-funding policy precluded its presence as WAF. The FWCW also marked a high point of cooperation with the government; many activists collaborated with the government to prepare the national report and half the official delegation comprised non-government women.

Donor-supported events leading up to the FWCW facilitated unprecedented interactions among activists. But a surge in funding opportunities accompanying the conferences led to a mushrooming of civil society organisations (CSOs), including women’s organisations, very few of which were movement-linked. Women’s organisations ceased to be principally places of affiliation and identity; like other CSOs, they also became places of employment, if at far below market rates.

The new millennium marks a new era. Even as self-proclaimed gender equality advocates multiplied, the women’s rights movement was less visible qua movement. The malaise was not limited to Pakistan. It was highlighted as a “mobilisational lull” in the context of Latin America by Sonia Alvarez, who also coined the term “NGO-isation” as early as 1999.

The contemporary women’s rights movement burst on to the scene in 1981, several years into the country’s most oppressive military dictatorship. Political parties were banned; politicians, trade unions and anyone who dared to oppose the regime ferociously suppressed; fundamental rights suspended; public hangings and floggings commonplace. For women, the challenge was the military’s “arrogat[ing] to itself the task of ‘Islamising’ the country’s institutions in their entirety” (Omar Asghar Khan, 1985).

As the least powerful group, women were easy targets and a way for the regime to demonstrate its ‘Islamic’ credentials. In a rigidly patriarchal society, there was no popular resistance to the almost casual rescinding of women’s rights. Women themselves did not respond in an organised manner until September 1981.

Igniting action was a small news item tucked away on an inside page, noticed by a Karachi-based women’s collective, the Shirkat Gah-Women’s Resource Centre. The news item reported that a woman (Fehmida) and a man (Allah Bux) had been sentenced respectively to 100 lashes and stoning to death under the soon-to-be-infamous Hudood Ordinances.

The promulgation of these ordinances in February 1979 had gone largely unnoticed during the trial of the ousted Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was hanged in April 1979. Shocked and bewildered by how such sentences could be legal, the collective decided it was time to act.

Given their limited numbers and the adverse circumstances, the single-most remarkable achievement of this entirely indigenous and unfunded movement was that it placed women and their rights squarely and permanently on the national agenda.

With only nine members, Shirkat Gah reached out to both women and men, urging collective action to prevent the sentences from being carried out. It was the diametrically opposed responses of women and men that galvanised the women’s movement. Men were either dismissive, believing such punishments would never be carried out in Pakistan, or defeatist, saying that individual citizens were helpless under martial law.

For women, these sentences represented the last straw. They were already angered by the regime’s numerous initiatives to curtail women’s rights, by the spiralling misogyny unleashed under the pretext of being more Islamic by people encouraged by state rhetoric, by the unprecedented harassment of women in public spaces, including women previously shielded by class privilege. Palpable anger and outrage at the meetings called by Shirkat Gah led to the formation of the Khawateen Mahaz-i-Amal, better known by its English name, the Women’s Action Forum (WAF). WAF chapters opened in quick succession in Lahore, Islamabad and Peshawar and, for a short while, in Abbottabad.

Led by WAF, the women’s movement mounted the most vociferous opposition to ‘Islamisation’ until Zia’s death in 1988. The relentless onslaught of legal and policy measures and proposals to curtail women’s rights demanded ceaseless activism. These included written and unwritten directives imposing ‘Islamic’ dress codes for a widening circle of women, barring female athletes from competitions, preventing women in the foreign ministry from serving abroad, imposing a moratorium on the recruitment and promotion of women in banks, an ‘anti-obscenity’ campaign seeking to eliminate women’s images from advertisements and in all media, and the Ansari Commission’s recommendations to seriously curtail women’s political participation.

Reducing the legal status of all women and non-Muslim men to half that of Muslim men started with the Hudood Ordinances, continued with the proposed ‘Law of Evidence’ and culminated in the proposed qisas and diyat law stipulating this ‘half-human’ status in black and white.

In the 1980s, women’s activism was reactive, state-focused and adversarial. The movement was led largely by middle- and upper-class working women who, having gained the most in their personal lives, stood to lose the most. But they were also better placed to face the risks of activism under martial law. Few of the new legal measures were likely to directly impact the personal lives of these activists. The fear was of a tsunami-like impact that the reducing of women’s legal rights, their further marginalisation and their exclusion from all decision-making positions would bring.

Numerous women’s organisations were involved but WAF provided the underlying coordination and strategic direction, becoming the face of the movement, a role facilitated by its policy of not accepting any funding other than personal donations and its principle of collective leadership that refused to acknowledge individual leaders, especially in the press.

With only a few hundred activists, the movement relied heavily on disrupting public spaces with street protests despite martial law prohibitions on public gatherings, to leverage attention, and on a supportive print media made more responsive given the ban on reporting political news, to amplify its message.

As a platform for individual women and women’s organisations, WAF initially adopted a minimal agenda for maximum buy-in, mobilising many women with no prior experience of, or inclination for, activism. Given the ban on politics, WAF deliberately called itself non-political. It reclassified itself as non-aligned and secular in 1991 and dropped the strategic use of Islam to counter laws proposed in the name of religion. A significant number of its activists were associated with progressive movements and participated in pro-democracy events, carefully explaining that this was in their individual capacity, not as WAF members — a distinction often lost on the press and on others.

With only a few hundred activists, the movement relied heavily on disrupting public spaces with street protests despite martial law prohibitions on public gatherings, to leverage attention, and on a supportive print media made more responsive given the ban on reporting political news, to amplify its message. Women’s defiance under martial law ensured public attention and media appreciation and earned the respect of politicians and other politically engaged actors.

Activists consciously engaged trade unions and political parties. Individual activists knew feminists and women’s groups abroad, but these links were irrelevant during this period, as the movement ignored international events and processes, including the 1985 UN World Conference on Women.

Given their limited numbers and the adverse circumstances, the single-most remarkable achievement of this entirely indigenous and unfunded movement was that it placed women and their rights squarely and permanently on the national agenda so that, for example, all political parties, including the conservative politico-religious Jamaat-i-Islami, started addressing women in their agendas. Other achievements included several discriminatory proposals curtailing women’s rights being abandoned, such as the Ansari Commission recommendations and a misogynist preacher’s programme on state-controlled television being discontinued.

The new discriminatory laws of evidence, and the qisas and diyat provisions in the law, could not be stopped but were delayed for years and enacted minus some of the most blatantly discriminatory aspects. Yet the Hudood Ordinances, having overturned the principle of presumed innocence, continued to fill the jails with women accused by former husbands, vindictive neighbours and random strangers, until the Women’s Protection Act of 2006; and the deep-seated changes wrought by Zia to the state and society continue to plague the country to this day. The current status of women’s activism has to be understood in the light of changes that occurred in the following two decades.

THE TRANSFORMATIVE DECADES

Zia’s death and the return of democracy in 1988 brought a major shift in the context and content of activism. The sense of urgency dissipated, political differences submerged in the struggle against a military dictator surfaced and activists returned to careers put on hold for almost a decade, reducing the number of proactive women.

Modalities changed: the skills of adversarial politics developed under martial law gave way to critically engaging authorities in less confrontational ways. Street protests became less frequent. New avenues for influencing were explored, facilitated by the links forged with politicians, and the fact that a significant number of women activists joined mainstream politics.

Several notable developments impacted the movement. Freed from incessantly countering anti-women moves, activists started defining their own agenda, demanding more rights and improved policies across a broad range of issues in addition to the rescinding of the zina laws and other regressive measures introduced by Zia.

The movement’s identity became more diffused. WAF ceased to be the movement’s singular face, although it still spearheaded some initiatives, for example, preventing the privatisation of the First Women Bank through a writ petition in court. Movement-linked women’s organisations took up issues for which they had no time under Zia, having understood how easily de jure rights can be overturned when so few women know about, much less enjoy, their rights.

Movement-linked women’s organisations took up issues for which they had no time under Zia, having understood how easily de jure rights can be overturned when so few women know about, much less enjoy, their rights.

Individual women’s organisations led initiatives on diverse issues such as political rights, education, health, workers’ rights, development policies and the need for a permanent commission on women to serve as a watchdog body. Media visibility waned as politics reclaimed centre stage. The movement reached fewer people as coverage was consigned to city pages, if carried at all.

During the unstable democracy of the 1990s, activists’ relationship with the state “vacillated between co-operation and collaboration with Benazir Bhutto [1988–90, 1993–96], and confrontation and contestation during the time of Nawaz Sharif [1990–93, 1997–99]” (Rubina Saigol, 2016). Threats to women’s rights became embedded in wider governance issues, such as the proposed Shariat Bill.

WAF mobilised a broader coalition with other human rights groups and religious minorities, subsequently formalised as the Joint Action Committee for People’s Rights, which started to articulate positions on many issues. An unintended consequence was the reduced visibility of women’s distinct voices.

A decade of extensive networking both within and outside the country replaced the inward-looking isolation under Zia, spurred in particular by the United Nations conferences on human rights (1993), population and development (1994) and, especially, the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (FWCW).

WAF engaged in the 1990s conferences, preparing position papers that were circulated to and by organisations and individuals from Pakistan and elsewhere, although WAF’s no-funding policy precluded its presence as WAF. The FWCW also marked a high point of cooperation with the government; many activists collaborated with the government to prepare the national report and half the official delegation comprised non-government women.

Donor-supported events leading up to the FWCW facilitated unprecedented interactions among activists. But a surge in funding opportunities accompanying the conferences led to a mushrooming of civil society organisations (CSOs), including women’s organisations, very few of which were movement-linked. Women’s organisations ceased to be principally places of affiliation and identity; like other CSOs, they also became places of employment, if at far below market rates.

The new millennium marks a new era. Even as self-proclaimed gender equality advocates multiplied, the women’s rights movement was less visible qua movement. The malaise was not limited to Pakistan. It was highlighted as a “mobilisational lull” in the context of Latin America by Sonia Alvarez, who also coined the term “NGO-isation” as early as 1999.

A young Asma Jahangir listens to a group of women | White Star ArchivesWhile the institutional wherewithal of organisations enables them to carry out certain initiatives better than individual activists, such as running women’s shelters, providing legal aid, systematic capacity building and rigorous research, worries that this NGO-isation was stultifying the movement started to be voiced. Underlying the malaise and lull were factors both internal and external to the movement.Internally, following the considerable energies invested in shaping the Beijing Platform as a governmental blueprint, many organisation-based activists focused their energies on concretising the promises secured. Some substantial gains were achieved, but this engagement shifted the agenda from a political to a more technical one.Because organisations concentrated on specific areas (for example, gender-based violence, education, political participation, workers’ rights), struggles took place in silos, dissipating the more cohesive dynamics of a united movement. Externally, the more technocratic Millennium Development Goals replaced the movement-informed Beijing Platform for Action.

Funding opportunities dwindled and were increasingly tied to “accounts-ability” (Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, 2015) and pre-set agendas, with donors pushing CSOs to adopt ever-more corporate business models. Bridging the two, the drive to secure funding led to competitiveness and a tendency to project organisational names rather than a collective movement identity.

In Pakistan, by this time, WAF was more of an organisation than a platform. Activists had become recognised names and the hidden hierarchies and power dynamics of decision-making had surfaced. Older activists failed to mobilise younger women to resist the Zia-reminiscent misogynist machinations of the Muttaheda Majlis-i-Amal (MMA), a coalition of politico-religious parties cobbled together by the new military ruler, Gen Pervez Musharraf (1999–2008).

The younger, urban, relatively well-off women they contacted favoured an all-embracing human rights and peace agenda over a separate women’s rights movement. Class privilege probably played a role, as less-privileged grassroots women engaged by women’s organisations were eager to learn about and resist patriarchy, albeit within the more immediate circles of family and community, shying away from addressing the state.

The net result, to use Amrita Basu’s terms, was a shift away from an organised gender equality movement to a more dispersed ‘feminism’. While both share similar goals and ideas, the distinction is that gender equality movements have specified entities enacting the ideas of equality using particular forms of engagement, whereas ‘feminism’ describes struggles for gender equality, connoting both ideas and their enactments, that are more dispersed.

This brings us to the contemporary period and the question of whether or not there is a movement today.

TODAY’S ACTIVISM: MOVEMENT OR NO MOVEMENT?

Since 2015, far more women than ever before self-identify as feminists and Pakistan has an articulate third generation of feminists. Some millennial activists have joined WAF but, although a new WAF chapter opened in Hyderabad in 2008 — quickly becoming the most active — and a WAF chapter has recently been launched in Quetta as well, these are led by women from the ‘in-between generation’ and WAF no longer provides the cohesive identity of a national movement as it once did.

Feeling marginalised in existing structures dominated by older women, young feminists have formed their own groups, often as collectives, including Girls at Dhabas, the Feminist Collective, Feminist Fridays, the Women’s Collective and the Women’s Democratic Front — some affiliated with left groups. The volition, modalities and priorities of young feminists differ significantly.

The concepts and praxis of activism are dissimilar. Older feminists, including many from the ‘in-between generation’, tend to conceive of activism in classical political terms and therefore focus collective action on state laws and policies, leaving the reshaping of the daily praxis of gender relations to personal initiatives.

In contrast, while some young feminists have engaged in important legislative processes, the majority concentrate on bringing about societal changes with a focus on personal lives.

Modalities differ. Aiming to change the contours and gender dynamics of the immediate communities they inhabit, younger feminists engage in the politics of presence, occupying physical and online spaces to do so. Today, social media, rather than mainstream news media, is the primary location of discursive battles in which younger women are more prominent.

Young feminists enjoin a more forceful expressive dimension of the movement through social media initiatives and novel approaches, such as stand-up comedy, an engagement that provides a crucial counterpoint to the aggressively waged discursive battle of far better resourced religious right forces. In the 1980s, activists did deploy humour, but fell short of fully developing an expressive dimension of the movement. Finally, today’s feminists prioritise sexuality, an issue that older activists always acknowledged but failed to address publicly.

The different priorities of the new generation are attributable, at least in part, to changed circumstances. The catalyst for activists of the 1980s movement, a state bent upon overturning women’s rights, is absent. Instead, the new generation confronts policing and harassment by social actors on a daily basis. The immediacy of these encounters and the ensuing frustrations make such issues seem more relevant than distant laws, propelling a greater interest in reshaping gender dynamics and power relations in everyday practices than in struggling to ensure rights by engaging with the state.

The failure of decades of activism to significantly change the daily reality of misogyny is likely to have prompted a loss of confidence in the state’s ability to achieve the desired change, deepening the reluctance to engage with the state in terms of challenging laws and policies or proposing new ones.

Without dispelling this mistrust and building bridges, activists will find it difficult to create the interconnected support system and coalescing force that lends activism a more definite movement identity, such as WAF provided earlier.

One advantage of society-focused activism is that it lends itself more easily to spontaneous actions of individuals or small groups of women — the dispersed feminism Basu refers to. In comparison, far greater organisational management is required to deploy and sustain concerted collective action typical of movements, especially those aiming to influence state policies. Over time, this management tends to become centralised and thus more hierarchical. It also often requires greater resources to maintain.

Engaging in society-oriented activism may be better placed to avoid binding structures and the need to secure finances. But transcending the confines of small actions entails its own dynamics and challenges, as evident when young feminists brought their politics, including of sexuality, on to the streets and into public view in 2018 and 2019.

On March 8, 2018, young feminists in Karachi organised the first Aurat March (Women’s March) under a new banner, Hum Aurtein (We Women). They were assisted by some older feminists. Thousands participated from all generations and classes, along with trans and rainbow activists. A smaller march was held in Lahore as well.

Unlike earlier demonstrations organised to protest against or demand something specific, Aurat March was an occasion for everyone to express themselves. The homemade placards were more imaginative and humorous than those seen at previous movement events. One stating ‘Heat your own food’ should have been unobjectionable but provoked a social media backlash.

The success of the Karachi march fired people’s imaginations and rallies multiplied the following year. In several major cities across the country, the 2019 Aurat March attracted thousands of people. In more remote areas such as Bannu, women held smaller rallies. A handful of placards (‘Warm your own bed’, ‘Keep dick pics to yourself’, an image of a woman sitting with her legs apart, stating ‘Now I am seated appropriately’) unleashed a furious misogynist reaction, including condemnation by lawmakers, family backlash and at least one attempt to file a police case against the organisers in Lahore.

These reactions conveniently ignored all the other posters demanding better working conditions, stronger laws, rights for workers and rural women and addressing many other ‘serious’ issues. They also ignored the presence of veiled women, including a burqa-clad woman whose placard read ‘My dress, my decision’.

Surprisingly, while many older activists were delighted that these crucial issues had finally been catapulted into the public arena, some felt the posters were inappropriate and risked alienating women. Forgetting the crucial role that notions of respectability play in maintaining patriarchy, these activists contributed, perhaps inadvertently, to the politics of respectability.

Other internal critics, who felt the posters detracted attention from the issues of rural and grassroots women, overlooked the fact that grassroots women themselves did not object. A positive and encouraging development is that a number of women legislators joined the Aurat March and reactions were not unidirectional: politicians, journalists and people on social media extended support as well.

TOWARDS THE FUTURE

Funding opportunities dwindled and were increasingly tied to “accounts-ability” (Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, 2015) and pre-set agendas, with donors pushing CSOs to adopt ever-more corporate business models. Bridging the two, the drive to secure funding led to competitiveness and a tendency to project organisational names rather than a collective movement identity.

In Pakistan, by this time, WAF was more of an organisation than a platform. Activists had become recognised names and the hidden hierarchies and power dynamics of decision-making had surfaced. Older activists failed to mobilise younger women to resist the Zia-reminiscent misogynist machinations of the Muttaheda Majlis-i-Amal (MMA), a coalition of politico-religious parties cobbled together by the new military ruler, Gen Pervez Musharraf (1999–2008).

The younger, urban, relatively well-off women they contacted favoured an all-embracing human rights and peace agenda over a separate women’s rights movement. Class privilege probably played a role, as less-privileged grassroots women engaged by women’s organisations were eager to learn about and resist patriarchy, albeit within the more immediate circles of family and community, shying away from addressing the state.

The net result, to use Amrita Basu’s terms, was a shift away from an organised gender equality movement to a more dispersed ‘feminism’. While both share similar goals and ideas, the distinction is that gender equality movements have specified entities enacting the ideas of equality using particular forms of engagement, whereas ‘feminism’ describes struggles for gender equality, connoting both ideas and their enactments, that are more dispersed.

This brings us to the contemporary period and the question of whether or not there is a movement today.

TODAY’S ACTIVISM: MOVEMENT OR NO MOVEMENT?

Since 2015, far more women than ever before self-identify as feminists and Pakistan has an articulate third generation of feminists. Some millennial activists have joined WAF but, although a new WAF chapter opened in Hyderabad in 2008 — quickly becoming the most active — and a WAF chapter has recently been launched in Quetta as well, these are led by women from the ‘in-between generation’ and WAF no longer provides the cohesive identity of a national movement as it once did.

Feeling marginalised in existing structures dominated by older women, young feminists have formed their own groups, often as collectives, including Girls at Dhabas, the Feminist Collective, Feminist Fridays, the Women’s Collective and the Women’s Democratic Front — some affiliated with left groups. The volition, modalities and priorities of young feminists differ significantly.

The concepts and praxis of activism are dissimilar. Older feminists, including many from the ‘in-between generation’, tend to conceive of activism in classical political terms and therefore focus collective action on state laws and policies, leaving the reshaping of the daily praxis of gender relations to personal initiatives.

In contrast, while some young feminists have engaged in important legislative processes, the majority concentrate on bringing about societal changes with a focus on personal lives.

Modalities differ. Aiming to change the contours and gender dynamics of the immediate communities they inhabit, younger feminists engage in the politics of presence, occupying physical and online spaces to do so. Today, social media, rather than mainstream news media, is the primary location of discursive battles in which younger women are more prominent.

Young feminists enjoin a more forceful expressive dimension of the movement through social media initiatives and novel approaches, such as stand-up comedy, an engagement that provides a crucial counterpoint to the aggressively waged discursive battle of far better resourced religious right forces. In the 1980s, activists did deploy humour, but fell short of fully developing an expressive dimension of the movement. Finally, today’s feminists prioritise sexuality, an issue that older activists always acknowledged but failed to address publicly.

The different priorities of the new generation are attributable, at least in part, to changed circumstances. The catalyst for activists of the 1980s movement, a state bent upon overturning women’s rights, is absent. Instead, the new generation confronts policing and harassment by social actors on a daily basis. The immediacy of these encounters and the ensuing frustrations make such issues seem more relevant than distant laws, propelling a greater interest in reshaping gender dynamics and power relations in everyday practices than in struggling to ensure rights by engaging with the state.

The failure of decades of activism to significantly change the daily reality of misogyny is likely to have prompted a loss of confidence in the state’s ability to achieve the desired change, deepening the reluctance to engage with the state in terms of challenging laws and policies or proposing new ones.

Without dispelling this mistrust and building bridges, activists will find it difficult to create the interconnected support system and coalescing force that lends activism a more definite movement identity, such as WAF provided earlier.

One advantage of society-focused activism is that it lends itself more easily to spontaneous actions of individuals or small groups of women — the dispersed feminism Basu refers to. In comparison, far greater organisational management is required to deploy and sustain concerted collective action typical of movements, especially those aiming to influence state policies. Over time, this management tends to become centralised and thus more hierarchical. It also often requires greater resources to maintain.

Engaging in society-oriented activism may be better placed to avoid binding structures and the need to secure finances. But transcending the confines of small actions entails its own dynamics and challenges, as evident when young feminists brought their politics, including of sexuality, on to the streets and into public view in 2018 and 2019.

On March 8, 2018, young feminists in Karachi organised the first Aurat March (Women’s March) under a new banner, Hum Aurtein (We Women). They were assisted by some older feminists. Thousands participated from all generations and classes, along with trans and rainbow activists. A smaller march was held in Lahore as well.

Unlike earlier demonstrations organised to protest against or demand something specific, Aurat March was an occasion for everyone to express themselves. The homemade placards were more imaginative and humorous than those seen at previous movement events. One stating ‘Heat your own food’ should have been unobjectionable but provoked a social media backlash.

The success of the Karachi march fired people’s imaginations and rallies multiplied the following year. In several major cities across the country, the 2019 Aurat March attracted thousands of people. In more remote areas such as Bannu, women held smaller rallies. A handful of placards (‘Warm your own bed’, ‘Keep dick pics to yourself’, an image of a woman sitting with her legs apart, stating ‘Now I am seated appropriately’) unleashed a furious misogynist reaction, including condemnation by lawmakers, family backlash and at least one attempt to file a police case against the organisers in Lahore.

These reactions conveniently ignored all the other posters demanding better working conditions, stronger laws, rights for workers and rural women and addressing many other ‘serious’ issues. They also ignored the presence of veiled women, including a burqa-clad woman whose placard read ‘My dress, my decision’.

Surprisingly, while many older activists were delighted that these crucial issues had finally been catapulted into the public arena, some felt the posters were inappropriate and risked alienating women. Forgetting the crucial role that notions of respectability play in maintaining patriarchy, these activists contributed, perhaps inadvertently, to the politics of respectability.

Other internal critics, who felt the posters detracted attention from the issues of rural and grassroots women, overlooked the fact that grassroots women themselves did not object. A positive and encouraging development is that a number of women legislators joined the Aurat March and reactions were not unidirectional: politicians, journalists and people on social media extended support as well.

TOWARDS THE FUTURE

Aurat March in Islamabad | Tanveer Shahzad/White Star

It is unclear whether this new activism will take the shape of an organised social movement or remain a period of more dispersed feminism. Generational differences among gender-equality activists are not unique to Pakistan. Across the globe, younger women are prioritising the politics of sexuality and, in Latin America for example, thousands of large rallies have been organised by women disenchanted with institutional activism, both with respect to more formal women’s organisations and direct engagement with the state.

Change is essential for movement continuity. The focus on sexuality of Pakistan’s younger generation fills an important gap in earlier activism, and their society-oriented activism complements the state-focused and policy-oriented struggle of older activists. However, state laws, policies and narratives always impact women’s lives in multifarious ways, and past experience makes it abundantly clear that the state can never be ignored. The experience of the 2019 Aurat March may propel younger feminists to greater engagement with the state. If not, this will leave a significant vacuum in the movement.

Keeping an eye on the state is all the more important as Pakistan pursues “the art of making dictatorship look like democracy” (Tom Hussain, 2018). New strategies are needed in the face of new challenges; the steady erosion of space for civil society, debate and dissent; increasing surveillance of CSOs and interference from intelligence agencies; and the use of terrorism threats to clamp down on human rights groups in Pakistan, as in other countries.

While women’s organisations that remain true to the ideals of feminism and linked to the movement can advance the movement by engaging with state institutions and providing institutional support, this may become increasingly difficult. Less formalised structures to achieve societal change may offer important advantages — one reason WAF never registered was to avoid such controls.

Internally, activists must overcome generational mistrust and bridge the approaches of differently located activists. Older activists believe that younger women tend to ignore the broader political dynamics, are less interested in structural change than in changing personal lives, and more interested in engaging with international movements than in building a national movement. The online activism of younger feminists is seen to exclude grassroots women, their actions are viewed as highly individualistic and some of their concerns are considered to be elitist.

Younger feminists believe that older activists operate in exclusionary hierarchies of power, have a know-it-all attitude that devalues younger women’s experience and perspective, and are resistant to listening to and learning from others.

Without dispelling this mistrust and building bridges, activists will find it difficult to create the interconnected support system and coalescing force that lends activism a more definite movement identity, such as WAF provided earlier. An important show of solidarity and strength, until very recently, the Aurat March was only an annual event and it is unclear whether Hum Aurtein is designed to operate as a movement in the future.

Without interconnectedness and identity, the different strands of activism and organisational bases risk remaining disparate initiatives, leaving Pakistani women’s rights activism in the ‘feminism’ state described by Basu, rather than as a recognisable movement.

Most recently, in September 2020, the immediate country-wide response to the gang-rape of a woman on the Lahore-Islamabad motorway, coupled with the outrageous misogynist statement of the Lahore Chief of Police (CCPO Umar Sheikh) on the incident, indicates that the women’s movement is very much alive — and also has numerous male supporters. Several demonstrations were co-organised by Aurat March, WAF and numerous other organisations.

With Aurat March stepping out of its role of being a once-a-year rallying point, it could become the leading face of the movement with others, including WAF, supporting it. This would certainly help to develop a more cohesive women’s and gender-equality movement.

The writer is a sociologist and human rights activist. She is the executive director of Shirkat Gah — Women’s Resource Centre in Pakistan and the co-author of the book Women of Pakistan: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back?

This essay originally appeared in Womansplaining: Navigating Activism, Politics and Modernity in Pakistan, published by Folio Books, 2021. The editor of Womansplaining, Sherry Rehman, is a fourth-term parliamentarian, the President of the Jinnah Institute and the Vice President of the Pakistan Peoples Party

A detailed bibliography of works cited and additional notes relevant to the essay can be found in the volume

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 12th, 2021

It is unclear whether this new activism will take the shape of an organised social movement or remain a period of more dispersed feminism. Generational differences among gender-equality activists are not unique to Pakistan. Across the globe, younger women are prioritising the politics of sexuality and, in Latin America for example, thousands of large rallies have been organised by women disenchanted with institutional activism, both with respect to more formal women’s organisations and direct engagement with the state.

Change is essential for movement continuity. The focus on sexuality of Pakistan’s younger generation fills an important gap in earlier activism, and their society-oriented activism complements the state-focused and policy-oriented struggle of older activists. However, state laws, policies and narratives always impact women’s lives in multifarious ways, and past experience makes it abundantly clear that the state can never be ignored. The experience of the 2019 Aurat March may propel younger feminists to greater engagement with the state. If not, this will leave a significant vacuum in the movement.

Keeping an eye on the state is all the more important as Pakistan pursues “the art of making dictatorship look like democracy” (Tom Hussain, 2018). New strategies are needed in the face of new challenges; the steady erosion of space for civil society, debate and dissent; increasing surveillance of CSOs and interference from intelligence agencies; and the use of terrorism threats to clamp down on human rights groups in Pakistan, as in other countries.

While women’s organisations that remain true to the ideals of feminism and linked to the movement can advance the movement by engaging with state institutions and providing institutional support, this may become increasingly difficult. Less formalised structures to achieve societal change may offer important advantages — one reason WAF never registered was to avoid such controls.

Internally, activists must overcome generational mistrust and bridge the approaches of differently located activists. Older activists believe that younger women tend to ignore the broader political dynamics, are less interested in structural change than in changing personal lives, and more interested in engaging with international movements than in building a national movement. The online activism of younger feminists is seen to exclude grassroots women, their actions are viewed as highly individualistic and some of their concerns are considered to be elitist.

Younger feminists believe that older activists operate in exclusionary hierarchies of power, have a know-it-all attitude that devalues younger women’s experience and perspective, and are resistant to listening to and learning from others.

Without dispelling this mistrust and building bridges, activists will find it difficult to create the interconnected support system and coalescing force that lends activism a more definite movement identity, such as WAF provided earlier. An important show of solidarity and strength, until very recently, the Aurat March was only an annual event and it is unclear whether Hum Aurtein is designed to operate as a movement in the future.

Without interconnectedness and identity, the different strands of activism and organisational bases risk remaining disparate initiatives, leaving Pakistani women’s rights activism in the ‘feminism’ state described by Basu, rather than as a recognisable movement.

Most recently, in September 2020, the immediate country-wide response to the gang-rape of a woman on the Lahore-Islamabad motorway, coupled with the outrageous misogynist statement of the Lahore Chief of Police (CCPO Umar Sheikh) on the incident, indicates that the women’s movement is very much alive — and also has numerous male supporters. Several demonstrations were co-organised by Aurat March, WAF and numerous other organisations.

With Aurat March stepping out of its role of being a once-a-year rallying point, it could become the leading face of the movement with others, including WAF, supporting it. This would certainly help to develop a more cohesive women’s and gender-equality movement.

The writer is a sociologist and human rights activist. She is the executive director of Shirkat Gah — Women’s Resource Centre in Pakistan and the co-author of the book Women of Pakistan: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back?

This essay originally appeared in Womansplaining: Navigating Activism, Politics and Modernity in Pakistan, published by Folio Books, 2021. The editor of Womansplaining, Sherry Rehman, is a fourth-term parliamentarian, the President of the Jinnah Institute and the Vice President of the Pakistan Peoples Party

A detailed bibliography of works cited and additional notes relevant to the essay can be found in the volume

Published in Dawn, EOS, September 12th, 2021