Poorly circulated room air raises potential exposure to contaminants by up to 6 times

Berkeley Lab experiments quantify the effects of overhead heating on room air mixing with implications for COVID-safe meetings and classrooms

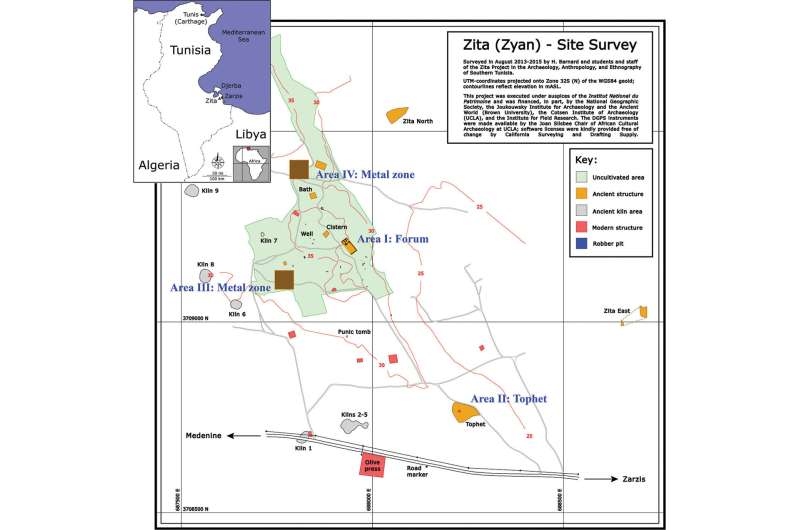

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: IN ONE OF THE ROOM CONFIGURATIONS, BERKELEY LAB RESEARCHERS PUT EIGHT PARTICIPANTS FACING INWARD LIKE IN A MEETING. ONE MANIKIN, DESIGNATED AS THE “SPEAKER,” WAS OUTFITTED WITH A DEVICE TO EXPEL AEROSOLS TO SIMULATE A PERSON TALKING. THE OTHER MANIKINS HAD A CO2 SENSOR AND OPTICAL PARTICLE COUNTER PLACED IN THEIR BREATHING ZONE. THERE WERE ALSO SENSORS THROUGHOUT THE ROOM TO MEASURE TEMPERATURE, AIR VELOCITY, AND CO2. view more

CREDIT: BERKELEY LAB

Having good room ventilation to dilute and disperse indoor air pollutants has long been recognized, and with the COVID-19 pandemic its importance has become all the more heightened. But new experiments by indoor air researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) show that certain circumstances will result in poor mixing of room air, meaning airborne contaminants may not be effectively dispersed and removed by building level ventilation.

Using CO2 as a tracer to track small respiratory aerosols that travel with air currents in a room, the Berkeley Lab team found that when overhead vents (or diffusers) are supplying heated air, it created thermally stratified conditions that block the flow of clean air down to the “breathing zone” in the middle height of the room. As a result, even when people are sitting more than 6 feet from each other, some occupants may be exposed to respiratory aerosols from others at a rate 5 to 6 times higher than if the same room were well mixed. Their study, “Measured influence of overhead HVAC on exposure to airborne contaminants from simulated speaking in a meeting and a classroom,” was published recently in the journal Indoor Air.

“When everything's well mixed, everybody's exposed to the same conditions,” said Berkeley Lab indoor air researcher Woody Delp. “When it’s not well mixed, you can have, from a COVID perspective, potential hot spots. So, if there’s one infected individual in the room, instead of having their expelled breath fully dispersed and then then properly diluted and removed by the HVAC system, another person sitting next to them or even across the room could get a high concentration of that infected person’s emitted viral aerosol.”

Delp notes that this situation would occur only in the case of heated air being supplied from the overhead diffusers. When cold or neutral air is being supplied, the researchers did not see the thermal stratification occur; instead, the room was found to be well mixed in those circumstances.

While the basic risk from overhead heating has been known for years, it had not previously been quantified under controlled but realistic conditions of a meeting or classroom. The results are important for understanding how large the risk can be when occupants are intentionally spaced for safety. “Ventilation is essential to maintaining good air quality,” said Brett Singer, the lead author of the study and head of Berkeley Lab’s Indoor Environment Group. “But if you’re heating overhead without intentionally mixing the air in the room, you will not get the full benefit of ventilation.”

Fortunately, there is a simple solution, the study found: using portable air cleaners that pull air in from below and push it out through the top. “They take care of the mixing and then they also filter the air, so they have a double benefit,” Singer said.

CAPTION

Berkeley Lab researcher Chelsea Preble helped conduct experiments on the movement of indoor air contaminants. Here she is controlling the aerosol emissions device in a room configured like classroom.

CREDIT

Berkeley Lab

9 dummies in a room

The researchers positioned eight thermal manikins (which are like retail display mannequins but used for scientific research instead) and had a researcher present to operate an aerosol emissions device in a 20-by-30-foot room set up first like a conference room, with participants seated in a circular pattern, then reconfigured like a classroom, with one standing at the front of the room and eight participants facing forward. Singer noted that most previous studies of the effects of imperfect mixing on contaminant dispersal used only one or two simulated occupants.

In this study, the manikins released plumes of heat, much like a person would. CO2 was released at mouth level to simulate small respiratory aerosols. The temperature of the CO2 as well as the velocity of its release were adjusted to simulate a person talking.

The experiments took place in the FLEXLAB(R), Berkeley Lab’s building simulator and test bed. “With the FLEXLAB, we were able to control every aspect of the HVAC system, which is how we were able to iterate on so many different conditions for the two types of occupancy configurations,” said Chelsea Preble, a research scientist at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley and a co-author on the study. “We were also able to have temperature and air velocity measurements throughout the room in addition to our measurements of CO2. Those helped us verify and quantify the mixing problem.”

Study limited to small aerosols only

Previous studies have established that CO2 can act as a proxy for the dispersion behavior of small respiratory aerosols, or particles less than 5 microns in size. A micron is one millionth of a meter. While respiratory aerosols are made up of particles in a vast range of sizes, from sub-micron to millimeters, this paper focuses on the smaller particles, which move mostly with the air currents. Larger particles, which behave differently, will be the subject of a future analysis.

“We released the particles and the CO2 at different manikins and tried to see how these tracers and particles spread around the room,” said Haoran Zhao, a Berkeley Lab postdoctoral fellow and co-author on the study. “We had CO2 sensors in each corner of the room at different heights and also at the breathing zone of each manikin.”

The authors are careful to note that their study addresses only the relative risk of poorly versus well-mixed conditions; it cannot be used directly to predict infection risk.

“We know the chain of events that it takes to get a person exposed, and it’s complicated and extraordinarily variable. An infected person talking and breathing expels droplets and aerosols of various sizes. But even when some of those are inhaled by someone else, they may or may not get infected,” Delp said. “From others’ studies, we know that the quantity of viruses emitted by an individual infected person can vary very widely. One person may expel millions more viruses than another infected person – and that varies over the course of an infection and also appears to be different for delta compared to the earlier variants. And to top it off, the number of viruses that it takes to initiate an infection also likely varies between people and with the sizes of the aerosols that are inhaled. As indoor air quality scientists and engineers, our focus is on what can be done with ventilation, filtration, and air distribution to reduce risks even when all the details of the biology are not known.”

The study was funded by the Department of Energy through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19. Other co-authors of the study were Jovan Pantelic, Michael Sohn, and Thomas Kirchstetter.

CAPTION

A release nozzle, placed at mouth level, released CO2, a tracer for tracking small respiratory aerosols that travel with air currents in a room.

CREDIT

Berkeley Lab

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 14 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

JOURNAL

Indoor Air

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Experimental study

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Not applicable

ARTICLE TITLE

Measured influence of overhead HVAC on exposure to airborne contaminants from simulated speaking in a meeting and a classroom