Quantifying change on barrier islands highlights the value of storms

Researchers have developed a methodology for quantifying landscape changes on barrier islands and, in doing so, have found the storms that can devastate human infrastructure also create opportunities for coastal wildlife to thrive.

"Our goal for this project was to develop a method to quantify land cover changes from natural processes and storms on barrier islands," says Beth Sciaudone, co-author of the study and a research assistant professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at North Carolina State University. "Ultimately, tracking and understanding these land changes can help us identify areas of coastal highway that are especially vulnerable to damage. It could also help us better understand how natural processes and infrastructure projects affect coastal wildlife habitat."

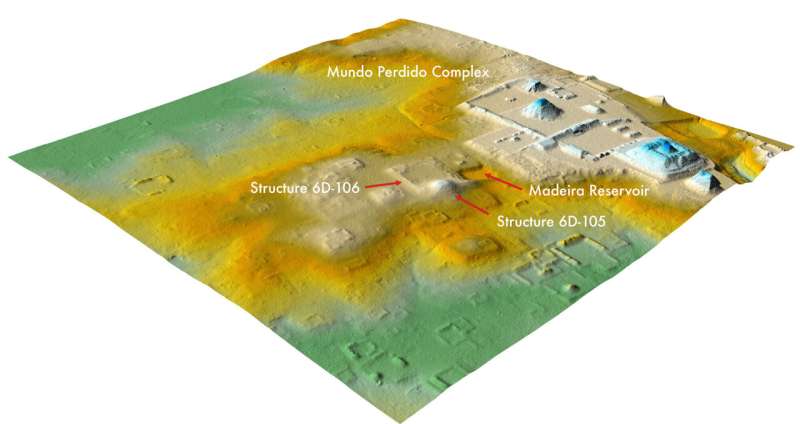

For this study, the researchers focused on Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, on North Carolina's Outer Banks. Specifically, the researchers made use of detailed, color-infrared images of the island that were taken each year from 2011 through 2018. These images allowed them to track changes in land cover across the island. The images were also used to create terrain models that let researchers assess changes in topography across the island.

Using these tools, the researchers were able to assess the land cover on the island and divide it into a dozen categories, such as beach, vegetated sand dunes, marsh and estuarine ponds. They could then measure the amount of each land-type on the island and how it changed over time. For example, there might be five total acres of marsh, including one acre of estuarine pond that had shifted to marsh over the past year.

But the researchers also noticed something else regarding the relationship between storms and wildlife habitat.

The images highlighted the extent to which Hurricane Irene in 2011, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, reshaped Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

"We already knew that bare sand is good wildlife habitat for many coastal species, but this work shed light on both how storms create habitat and how long that habitat lasts," Sciaudone says.

What the researchers found was that, on barrier islands, a lot depends on which direction the storm is coming from. For example, Hurricane Irene hit Pea Island from the Pamlico Sound to the west, while Hurricane Sandy hit the island from the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Both storms caused noteworthy changes in land cover. However, the long-term impact of the two storms has varied significantly.

When Hurricane Sandy wiped out vegetation, creating areas of bare sand, it took three to four years for the vegetation to recover. Meanwhile, Hurricane Irene fundamentally changed the hydrodynamics on the western side of the island, increasing the amount of habitat hospitable for shorebirds and other coastal species.

"Evaluating these habitat changes directly informs conservation management decisions on the refuge and helps us prioritize resource protection and restoration actions," says Rebecca Harrison, co-author of the study and supervisory refuge wildlife biologist at the refuge for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

"The methodology that we've developed here could be used to help quantify changes on barrier islands anywhere," Sciaudone says. "And working with regional wildlife experts can help us understand what those land cover changes mean for habitat.

"The takeaway is that we need to ensure our efforts to build and preserve coastal infrastructure take into account the role that coastal erosion and related natural processes play in creating and preserving wildlife habitat—and the work we've done here can inform that sort of decision-making."

The paper, "Land cover changes on a barrier island: Yearly changes, storm effects, and recovery periods," is published in Applied Geography. Corresponding author of the study is Liliana Velasquez-Montoya, an assistant professor at the U.S. Naval Academy who worked on the project while a postdoctoral researcher at NC State. Co-authors include Margery Overton, a professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at NC State; and Rebecca Harrison of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. The work was done with support from the North Carolina Department of Transportation.'Crazy' ants that kill birds eradicated from Pacific atoll

More information: Liliana Velasquez-Montoya et al, Land cover changes on a barrier island: Yearly changes, storm effects, and recovery periods, Applied Geography (2021). DOI: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102557

Provided by North Carolina State University