What makes us human? The answer may be found in overlooked DNA

Our DNA is very similar to that of the chimpanzee, which in evolutionary terms is our closest living relative. Stem cell researchers at Lund University in Sweden have now found a previously overlooked part of our DNA, so-called non-coded DNA, that appears to contribute to a difference which, despite all our similarities, may explain why our brains work differently. The study is published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

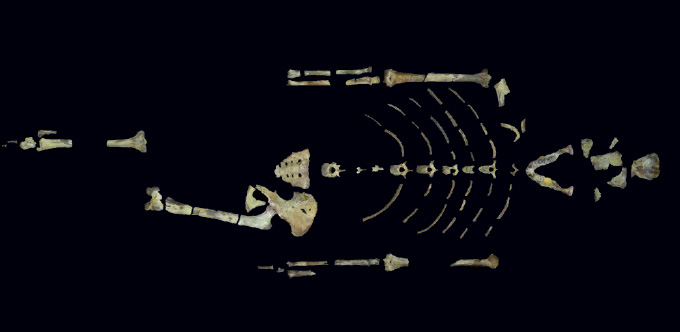

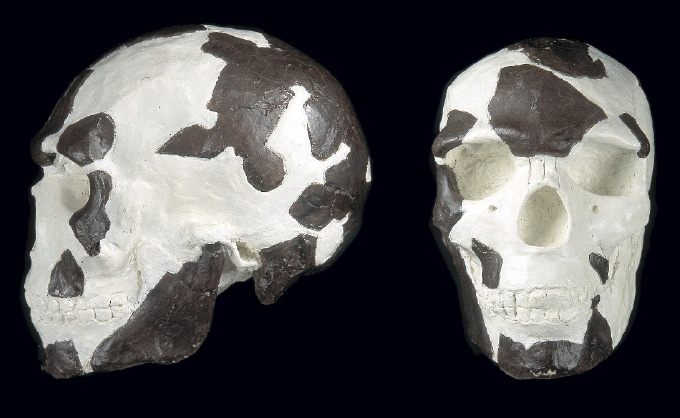

The chimpanzee is our closest living relative in evolutionary terms and research suggests our kinship derives from a common ancestor. About five to six million years ago, our evolutionary paths separated, leading to the chimpanzee of today, and Homo Sapiens, humankind in the 21st century.

In a new study, stem cell researchers at Lund examined what it is in our DNA that makes human and chimpanzee brains different—and they have found answers.

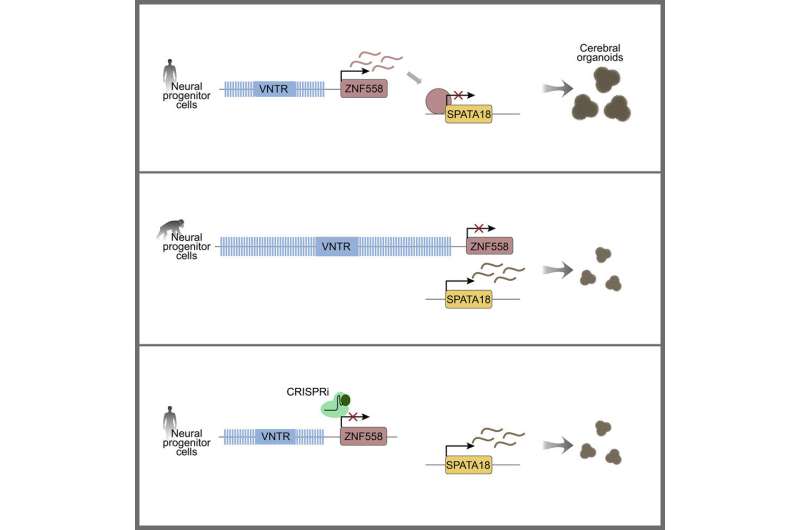

"Instead of studying living humans and chimpanzees, we used stem cells grown in a lab. The stem cells were reprogrammed from skin cells by our partners in Germany, the U.S. and Japan. Then we examined the stem cells that we had developed into brain cells," explains Johan Jakobsson, professor of neuroscience at Lund University, who led the study.

Using the stem cells, the researchers specifically grew brain cells from humans and chimpanzees and compared the two cell types. The researchers then found that humans and chimpanzees use a part of their DNA in different ways, which appears to play a considerable role in the development of our brains.

"The part of our DNA identified as different was unexpected. It was a so-called structural variant of DNA that were previously called "junk DNA," a long repetitive DNA string which has long been deemed to have no function. Previously, researchers have looked for answers in the part of the DNA where the protein-producing genes are—which only makes up about two percent of our entire DNA—and examined the proteins themselves to find examples of differences."

The new findings thus indicate that the differences appear to lie outside the protein-coding genes in what has been labeled as "junk DNA," which was thought to have no function and which constitutes the majority of our DNA.

"This suggests that the basis for the human brain's evolution are genetic mechanisms that are probably a lot more complex than previously thought, as it was supposed that the answer was in those two percent of the genetic DNA. Our results indicate that what has been significant for the brain's development is instead perhaps hidden in the overlooked 98 percent, which appears to be important. This is a surprising finding."

The stem cell technique used by the researchers in Lund is revolutionary and has enabled this type of research. The technique was recognized by the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. It was the Japanese researcher Shinya Yamanaka who discovered that specialized cells can be reprogrammed and developed into all types of body tissue. And in the Lund researchers' case, into brain cells. Without this technique, it would not have been possible to study the differences between humans and chimpanzees using ethically defensible methods.

Why did the researchers want to investigate the difference between humans and chimpanzees?

"I believe that the brain is the key to understanding what it is that makes humans human. How did it come about that humans can use their brain in such a way that they can build societies, educate their children and develop advanced technology? It is fascinating!"

Johan Jakobsson believes that in the future the new findings may also contribute to genetically-based answers to questions about psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, a disorder that appears to be unique to humans.

"But there is a long way to go before we reach that point, as instead of carrying out further research on the two percent of coded DNA, we may now be forced to delve deeper into all 100 percent—a considerably more complicated task for research," he concludes.Scientists discover how humans develop larger brains than other apes

More information: Pia A. Johansson et al, A cis-acting structural variation at the ZNF558 locus controls a gene regulatory network in human brain development, Cell Stem Cell (2021). doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2021.09.008

Journal information: Cell Stem Cell

Provided by Cell Press