Pacific island countries have refused to be the canary in the world’s coal mine at CoP26

By Wesley Morgan

Published: Friday 22 October 2021

The Pacific Islands are at the frontline of climate change. But as rising seas threaten their very existence, these tiny nation states will not be submerged without a fight.

For decades this group has been the world’s moral conscience on climate change. Pacific leaders are not afraid to call out the climate policy failures of far bigger nations, including regional neighbour Australia.

And they have a strong history of punching above their weight at United Nations climate talks — including at Paris, where they were credited with helping secure the first truly global climate agreement.

The momentum is with Pacific island countries at next month’s summit in Glasgow and they have powerful friends. The United Kingdom, European Union and United States all want to see warming limited to 1.5℃.

This powerful alliance will turn the screws on countries dragging down the global effort to avert catastrophic climate change. And if history is a guide, the Pacific won’t let the actions of laggard nations go unnoticed.

A long fight for survival

Pacific leaders’ agitation for climate action dates back to the late 1980s, when scientific consensus on the problem emerged. The leaders quickly realised the serious implications global warming and sea-level rise posed for island countries.

Some Pacific nations — such as Kiribati, Marshall Islands and Tuvalu — are predominantly low-lying atolls, rising just metres above the waves. In 1991, Pacific leaders declared “the cultural, economic and physical survival of Pacific nations is at great risk”.

Successive scientific assessments clarified the devastating threat climate change posed for Pacific nations: More intense cyclones, changing rainfall patterns, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, coastal inundation and sea-level rise.

Pacific states developed collective strategies to press the international community to take action. At past UN climate talks, they formed a diplomatic alliance with island nations in the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean, which swelled to more than 40 countries.

The first draft of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol — which required wealthy nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions — was put forward by Nauru on behalf of this Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS).

Read more: Australia ranks last out of 54 nations on its strategy to cope with climate change. The Glasgow summit is a chance to protect us all

Climate change is a threat to the survival of Pacific Islanders. Mick Tsikas/AAPSecuring a global agreement in Paris

Pacific states were also crucial in negotiating a successor to the Kyoto Protocol in Paris in 2015.

By this time, UN climate talks were stalled by arguments between wealthy nations and developing countries about who was responsible for addressing climate change, and how much support should be provided to help poorer nations to deal with its impacts.

In the months before the Paris climate summit, then-Marshall Islands Foreign Minister, the late Tony De Brum, quietly coordinated a coalition of countries from across traditional negotiating divides at the UN.

This was genius strategy. During talks in Paris, membership of this “High Ambition Coalition” swelled to more than 100 countries, including the European Union and the United States, which proved vital for securing the first truly global climate agreement.

When then-US President Barack Obama met with island leaders in 2016, he noted “we could not have gotten a Paris Agreement without the incredible efforts and hard work of island nations”.

The High Ambition Coalition secured a shared temperature goal in the Paris Agreement, for countries to limit global warming to 1.5℃ above the long-term average. This was no arbitrary figure.

Scientific assessments have clarified 1.5℃ warming is a key threshold for the survival of vulnerable Pacific Island states and the ecosystems they depend on, such as coral reefs.

Read more: Who's who in Glasgow: 5 countries that could make or break the planet's future under climate change

Pacific states were also crucial in negotiating a successor to the Kyoto Protocol in Paris in 2015.

By this time, UN climate talks were stalled by arguments between wealthy nations and developing countries about who was responsible for addressing climate change, and how much support should be provided to help poorer nations to deal with its impacts.

In the months before the Paris climate summit, then-Marshall Islands Foreign Minister, the late Tony De Brum, quietly coordinated a coalition of countries from across traditional negotiating divides at the UN.

This was genius strategy. During talks in Paris, membership of this “High Ambition Coalition” swelled to more than 100 countries, including the European Union and the United States, which proved vital for securing the first truly global climate agreement.

When then-US President Barack Obama met with island leaders in 2016, he noted “we could not have gotten a Paris Agreement without the incredible efforts and hard work of island nations”.

The High Ambition Coalition secured a shared temperature goal in the Paris Agreement, for countries to limit global warming to 1.5℃ above the long-term average. This was no arbitrary figure.

Scientific assessments have clarified 1.5℃ warming is a key threshold for the survival of vulnerable Pacific Island states and the ecosystems they depend on, such as coral reefs.

Read more: Who's who in Glasgow: 5 countries that could make or break the planet's future under climate change

Warming above 1.5℃ threatens Pacific Island states and their coral reefs. Shutterstock

De Brum took a powerful slogan to Paris: “1.5 to stay alive”.

The Glasgow summit is the last chance to keep 1.5℃ of warming within reach. But Australia — almost alone among advanced economies — is taking to Glasgow the same 2030 target it took to Paris six years ago. This is despite the Paris Agreement requirement that nations ratchet up their emissions-reduction ambition every five years.

Australia is the largest member of the Pacific Islands Forum (an intergovernmental group that aims to promote the interests of countries and territories in the Pacific). But it’s also a major fossil fuel producer, putting it at odds with other Pacific countries on climate.

When Australia announced its 2030 target, De Brum said if the rest of the world followed suit:

the Great Barrier Reef would disappear […] so would the Marshall Islands and other vulnerable nations.

Influence at Glasgow

So what can we expect from Pacific leaders at the Glasgow summit? The signs so far suggest they will demand CoP26 deliver an outcome to once and for all limit global warming to 1.5℃.

At pre-CoP discussions in Milan earlier this month, vulnerable nations proposed countries be required to set new 2030 targets each year until 2025 — a move intended to bring global ambition into alignment with a 1.5℃ pathway.

COP26 president Alok Sharma says he wants the decision text from the summit to include a new agreement to keep 1.5℃ within reach.

This sets the stage for a showdown. Major powers like the US and the EU are set to work with large negotiating blocs, like the High Ambition Coalition, to heap pressure on major emitters that have yet to commit to serious 2030 ambition — including China, India, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Australia.

The chair of the Pacific Islands Forum, Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, has warned Pacific island countries “refuse to be the canary in the world’s coal mine.”

According to Bainimarama:

by the time leaders come to Glasgow, it has to be with immediate and transformative action […] come with commitments for serious cuts in emissions by 2030 — 50 per cent or more. Come with commitments to become net zero before 2050. Do not come with excuses. That time is past.

Wesley Morgan, Researcher, Climate Council, and Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

De Brum took a powerful slogan to Paris: “1.5 to stay alive”.

The Glasgow summit is the last chance to keep 1.5℃ of warming within reach. But Australia — almost alone among advanced economies — is taking to Glasgow the same 2030 target it took to Paris six years ago. This is despite the Paris Agreement requirement that nations ratchet up their emissions-reduction ambition every five years.

Australia is the largest member of the Pacific Islands Forum (an intergovernmental group that aims to promote the interests of countries and territories in the Pacific). But it’s also a major fossil fuel producer, putting it at odds with other Pacific countries on climate.

When Australia announced its 2030 target, De Brum said if the rest of the world followed suit:

the Great Barrier Reef would disappear […] so would the Marshall Islands and other vulnerable nations.

Influence at Glasgow

So what can we expect from Pacific leaders at the Glasgow summit? The signs so far suggest they will demand CoP26 deliver an outcome to once and for all limit global warming to 1.5℃.

At pre-CoP discussions in Milan earlier this month, vulnerable nations proposed countries be required to set new 2030 targets each year until 2025 — a move intended to bring global ambition into alignment with a 1.5℃ pathway.

COP26 president Alok Sharma says he wants the decision text from the summit to include a new agreement to keep 1.5℃ within reach.

This sets the stage for a showdown. Major powers like the US and the EU are set to work with large negotiating blocs, like the High Ambition Coalition, to heap pressure on major emitters that have yet to commit to serious 2030 ambition — including China, India, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Australia.

The chair of the Pacific Islands Forum, Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, has warned Pacific island countries “refuse to be the canary in the world’s coal mine.”

According to Bainimarama:

by the time leaders come to Glasgow, it has to be with immediate and transformative action […] come with commitments for serious cuts in emissions by 2030 — 50 per cent or more. Come with commitments to become net zero before 2050. Do not come with excuses. That time is past.

Wesley Morgan, Researcher, Climate Council, and Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fighting climate change: Why we need more policy experts, green jobs in India

We cannot leave the creation of green jobs to the future; they need to be created now

By Tanya Mittal

Published: Friday 22 October 2021

Climate change has come a long way since it faced scepticism and resistance: 2021, with all its trappings of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic aside, has made a clear case that the crisis is real. The task at hand is huge — at the individual, national and international levels.

Transitioning to a decarbonised economy is a crucial step to halt the impending crisis. It also drives economic growth by creating green jobs.

Green jobs not only provide much-required employment opportunities for the youth, but they also give youngsters an outlet to contribute directly and actively to planetary health. The non-use of natural resources such as fossil fuels can considerably change people’s lifestyles.

The other resources — power from hydroelectric, solar and (made-safe) nuclear energy — should be made available in a quantity that we can do without the natural resources (coal, fuels, gas, wood, etc.).

Discarding the use of plastic and other synthetic materials, replacing them with biodegradable materials, discarding potentially toxic fertilisers and insecticide sprays, are among the well-documented can help restore the skewed balance in nature.

We need to take responsibility of change on ourselves:

Transitioning to cleaner fuel, using electric cars, walking and cycling more

Avoiding wastage of resources, including water and food items

Sparingly using consumables and energy (like electricity, gas, fuels)

The need to pre-stage public resistance by educating people appropriately is filled by climate policy professionals and specialists. Various think tanks and climate organisations have a good vantage point to directly combat a worsening climatic environment and extinguish the citizen ire regarding fuel price hikes or similar government measures.

Floods, landslides, droughts, forest fires, melting glaciers and rising temperatures have wreaked havoc all over the world. Even climate change deniers are not delusional anymore. And this is a good development.

Several studies anticipated that low-lying coastal lands and delta-lands (like in Bangladesh) would go under seawater in the near future. This would result in the forced climate-induced migration of large populations.

We cannot leave the creation of green jobs to the future; they need to be created now. Incentives should be provided for people to actively fight climate change and lead a lifestyle that is gentle to the environment. At the international level, all stakeholders need to cooperate promptly and effectively to bring about these changes.

There is a common misnomer about green jobs: That the work is only related to sustaining a healthy environment. The ambit has, however, expanded to cover a larger portion of the economy, with principles of environmentalism, conservation, regulation and equity and investment at core.

New information comes to light every day, including data, research and recommendations by the scientific fraternity. The transition to adopting green jobs and practices would advance social change too.

Climate policy action is for the common man and green jobs are meant to promote inclusive growth strategy for poverty reduction, environmentally sustainable paths and local development initiatives.

The Green Jobs Initiative by the International Labour Organisation and its partners seeks to address such issues by promoting economies and small enterprises with reduced carbon footprint, environmental ramifications and conservation of natural resources.

What is CoP26? Here’s how global climate negotiations work and what’s expected from the Glasgow summit

CoP26 will be a complex process, but it’s how international law and institutions can help solve problems that no single country can fix on its own

By Shelley Inglis

Published: Thursday 21 October 2021

Over two weeks in November, world leaders and national negotiators will meet in Scotland to discuss what to do about climate change. It’s a complex process that can be hard to make sense of from the outside, but it’s how international law and institutions help solve problems that no single country can fix on its own.

I worked for the United Nations for several years as a law and policy adviser and have been involved in international negotiations. Here’s what’s happening behind closed doors and why people are concerned that CoP26 might not meet its goals.

What is CoP26?

In 1992, countries agreed to an international treaty called the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which set ground rules and expectations for global cooperation on combating climate change. It was the first time the majority of nations formally recognised the need to control greenhouse gas emissions, which cause global warming that drives climate change.

That treaty has since been updated, including in 2015 when nations signed the Paris climate agreement. That agreement set the goal of limiting global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 F), and preferably to 1.5 C (2.7 F), to avoid catastrophic climate change.

CoP26 stands for the 26th Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC. The “parties” are the 196 countries that ratified the treaty plus the European Union. The United Kingdom, partnering with Italy, is hosting CoP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, from October 31 through November 12, 2021, after a one-year postponement due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why are world leaders so focused on climate change?

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report, released in August 2021, warns in its strongest terms yet that human activities have unequivocally warmed the planet and that climate change is now widespread, rapid and intensifying.

The IPCC’s scientists explain how climate change has been fueling extreme weather events and flooding, severe heat waves and droughts, loss and extinction of species and the melting of ice sheets and rising of sea levels. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the report a “code red for humanity.”

Enough greenhouse gas emissions are already in the atmosphere and they stay there long enough, that even under the most ambitious scenario of countries quickly reducing their emissions, the world will experience rising temperatures through at least mid-century.

However, there remains a narrow window of opportunity. If countries can cut global emissions to “net zero” by 2050, that could bring warming back to under 1.5 C in the second half of the 21st century. How to get closer to that course is what leaders and negotiators are discussing.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called the latest climate science findings a ‘code red for humanity.’

UNFCCCWhat happens at CoP26?

During the first days of the conference, around 120 heads of state, like US President Joe Biden and their representatives will gather to demonstrate their political commitment to slowing climate change.

Once the heads of state depart, country delegations, often led by ministers of environment, engage in days of negotiations, events and exchanges to adopt their positions, make new pledges and join new initiatives. These interactions are based on months of prior discussions, policy papers and proposals prepared by groups of states, UN staff and other experts.

Nongovernmental organisations and business leaders also attend the conference and CoP26 has a public side with sessions focused on topics such as the impact of climate change on small island states, forests or agriculture, as well as exhibitions and other events.

The meeting ends with an outcome text that all countries agree to. Guterres publicly expressed disappointment with the CoP25 outcome and there are signs of trouble heading into CoP26.

During the first days of the conference, around 120 heads of state, like US President Joe Biden and their representatives will gather to demonstrate their political commitment to slowing climate change.

Once the heads of state depart, country delegations, often led by ministers of environment, engage in days of negotiations, events and exchanges to adopt their positions, make new pledges and join new initiatives. These interactions are based on months of prior discussions, policy papers and proposals prepared by groups of states, UN staff and other experts.

Nongovernmental organisations and business leaders also attend the conference and CoP26 has a public side with sessions focused on topics such as the impact of climate change on small island states, forests or agriculture, as well as exhibitions and other events.

The meeting ends with an outcome text that all countries agree to. Guterres publicly expressed disappointment with the CoP25 outcome and there are signs of trouble heading into CoP26.

Celebrities like youth climate activist Greta Thunberg add public pressure on world leaders.

UNFCCCWhat is CoP26 expected to accomplish?

Countries are required under the Paris Agreement to update their national climate action plans every five years, including at CoP26. This year, they’re expected to have ambitious targets through 2030. These are known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs.

The Paris Agreement requires countries to report their NDCs, but it allows them leeway in determining how they reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. The initial set of emission reduction targets in 2015 was far too weak to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

One key goal of CoP26 is to ratchet up these targets to reach net zero carbon emissions by the middle of the century.

Another aim of CoP26 is to increase climate finance to help poorer countries transition to clean energy and adapt to climate change. This is an important issue of justice for many developing countries whose people bear the largest burden from climate change but have contributed least to it.

Wealthy countries promised in 2009 to contribute $100 billion a year by 2020 to help developing nations, a goal that has not been reached. The US, UK and EU, among the largest historic greenhouse emitters, are increasing their financial commitments and banks, businesses, insurers and private investors are being asked to do more.

Other objectives include phasing out coal use and generating solutions that preserve, restore or regenerate natural carbon sinks, such as forests.

Another challenge that has derailed past CoPs is agreeing on implementing a carbon trading system outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Countries are required under the Paris Agreement to update their national climate action plans every five years, including at CoP26. This year, they’re expected to have ambitious targets through 2030. These are known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs.

The Paris Agreement requires countries to report their NDCs, but it allows them leeway in determining how they reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. The initial set of emission reduction targets in 2015 was far too weak to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

One key goal of CoP26 is to ratchet up these targets to reach net zero carbon emissions by the middle of the century.

Another aim of CoP26 is to increase climate finance to help poorer countries transition to clean energy and adapt to climate change. This is an important issue of justice for many developing countries whose people bear the largest burden from climate change but have contributed least to it.

Wealthy countries promised in 2009 to contribute $100 billion a year by 2020 to help developing nations, a goal that has not been reached. The US, UK and EU, among the largest historic greenhouse emitters, are increasing their financial commitments and banks, businesses, insurers and private investors are being asked to do more.

Other objectives include phasing out coal use and generating solutions that preserve, restore or regenerate natural carbon sinks, such as forests.

Another challenge that has derailed past CoPs is agreeing on implementing a carbon trading system outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Chinese street vendors sell vegetables outside a state-owned coal-fired power plant in 2017. Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Are countries on track to meet the international climate goals?

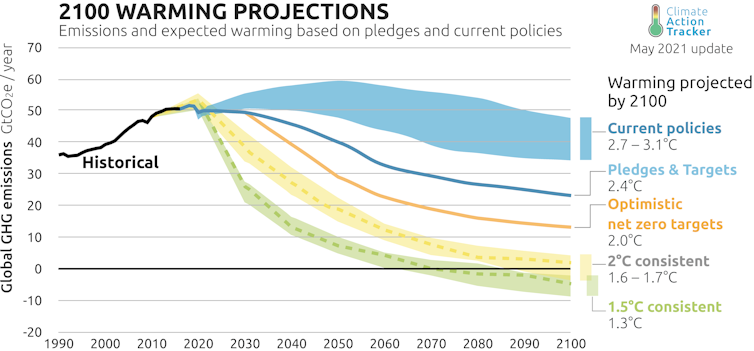

The UN warned in September 2021 that countries’ revised targets were too weak and would leave the world on pace to warm 2.7 C (4.9 F) by the end of the century. However, governments are also facing another challenge this fall that could affect how they respond: Energy supply shortages have left Europe and China with price spikes for natural gas, coal and oil.

China — the world’s largest emitter — has not yet submitted its NDC. Major fossil fuel producers such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and Australia seem unwilling to strengthen their commitments. India — a critical player as the second-largest consumer, producer and importer of coal globally — has also not yet committed.

Other developing nations such as Indonesia, Malaysia, South Africa and Mexico are important. So is Brazil, which, under Javier Bolsonaro’s watch, has increased deforestation of the Amazon — the world’s largest rainforest and crucial for biodiversity and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

What happens if CoP26 doesn’t meet its goals?

Many insiders believe that CoP26 won’t reach its goal of having strong enough commitments from countries to cut global greenhouse gas emissions 45 per cent by 2030. That means the world won’t be on a smooth course for reaching net zero emissions by 2050 and the goal of keeping warming under 1.5 C.

But organisers maintain that keeping warming under 1.5 C is still possible. Former Secretary of State John Kerry, who has been leading the US negotiations, remains hopeful that enough countries will create momentum for others to strengthen their reduction targets by 2025.

The UN warned in September 2021 that countries’ revised targets were too weak and would leave the world on pace to warm 2.7 C (4.9 F) by the end of the century. However, governments are also facing another challenge this fall that could affect how they respond: Energy supply shortages have left Europe and China with price spikes for natural gas, coal and oil.

China — the world’s largest emitter — has not yet submitted its NDC. Major fossil fuel producers such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and Australia seem unwilling to strengthen their commitments. India — a critical player as the second-largest consumer, producer and importer of coal globally — has also not yet committed.

Other developing nations such as Indonesia, Malaysia, South Africa and Mexico are important. So is Brazil, which, under Javier Bolsonaro’s watch, has increased deforestation of the Amazon — the world’s largest rainforest and crucial for biodiversity and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

What happens if CoP26 doesn’t meet its goals?

Many insiders believe that CoP26 won’t reach its goal of having strong enough commitments from countries to cut global greenhouse gas emissions 45 per cent by 2030. That means the world won’t be on a smooth course for reaching net zero emissions by 2050 and the goal of keeping warming under 1.5 C.

But organisers maintain that keeping warming under 1.5 C is still possible. Former Secretary of State John Kerry, who has been leading the US negotiations, remains hopeful that enough countries will create momentum for others to strengthen their reduction targets by 2025.

The world is not on track to meet the Paris goal. Climate Action Tracker

The cost of failure is astronomical. Studies have shown that the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius can mean the submersion of small island states, the death of coral reefs, extreme heat waves, flooding and wildfires and pervasive crop failure.

That translates into many premature deaths, more mass migration, major economic losses, large swaths of unlivable land and violent conflict over resources and food — what the UN secretary-general has called “a hellish future.”

[Get The Conversation’s most important politics headlines, in our Politics Weekly newsletter.]

Shelley Inglis, Executive Director, University of Dayton Human Rights Center, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UNEP production gap report: Net-zero targets by countries are empty pledges without plans

Governments are planning to produce more than double the production of fossil fuels than what the world requires to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius

By Samrat Sengupta

Published: Wednesday 20 October 2021

The climate crisis has become clearer than ever, but it has not been able to compel major emitters to improve action on the ground so far. Governments across the world are still planning to produce more than double the fossil fuels than what the world requires to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

This was flagged by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report released October 20, 2021.

The production gap to achieve the climate goal is the widest for coal: Production plans and projections by governments would lead to around 240 per cent more coal, 57 per cent more oil, and 71 per cent more gas in 2030 than global levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.

The modelling analysis has considered carbon dioxides removal (CDR) technologies to be deployed widely and methane emissions and leakages to be arrested. These assumptions are yet to be proven workable in practice and any deviation from the assumptions will lead to further widening of the gap.

Global fossil fuel production under four pathways from 2019 to 2040, denominated in extraction-based CO2 emissions in units of billion tonnes of CO2 per year (GtCO2/yr). This reflects the amount of CO2 emissions expected to be released from the combustion of extracted coal, oil, and gas. Source: Production Gap Report 2021, UNEP

The most worrying factor is that almost all major coal, oil and gas producers are planning to increase their production till at least 2030 or beyond.

This has been fuelled by incremental capital flow towards fossil fuels in comparison to clean energy in the post novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) recovery phase. The Group of 20 countries has channelised $300 billion to fossil fuels since the beginning of the pandemic, and the sector is still enjoying significant fiscal incentives.

The world does not have any more time to alter its trajectory of energy use from fossil to clean energy, and a slight deviation in the coming decade will have a substantial burden of adversaries to our future generations, as we will be locked into long-term human-induced global warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius.

The world leaders have planned to meet during the first half of November 2021, at the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Glasgow, United Kingdom, to negotiate on pathways to avert this crisis.

The report has underlined massive gaps between our pledges and actions, which need to be rectified with a real policy plan and finance.

Published: Monday 18 October 2021

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a potent greenhouse gas. It is abundant and stays in the atmosphere for a long time. It is responsible for about 66 per cent the total energy imbalance that has been causing the Earth’s temperature to rise.

It also dissolves in the ocean water, producing carbonic acid and lowering the ocean’s pH. This adversely affects the marine life. CO2 is one of the most notorious gases contributing to the changing climate.

To achieve the results pledged under Paris Agreement, 2015 to limit future temperature increases to 1.5 degree Celsius, emission reduction may just not be sufficient.

Literal removal of carbon from the atmosphere is vital to achieve the target, without which the cascade effect will result in catastrophic events, including sinking of the world’s important cities. It will pose risks to roads, railways, ports, underwater internet cables, farmland, sanitation and drinking water pipelines and reservoirs as well as even mass transit systems.

Some cities will disappear from the world map; others will need to become resilient to this change. Around 90 per cent of all coastal areas will be affected to varying degrees, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Risk Report.

To address the risks, we need to deploy technologies to remove carbon from the atmosphere apart in addition to reducing emissions. Mass and Aggressive Afforestation (MAA) and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) are the primary ways of doing it.

MAA is more of a natural process, which also requires land recovery from existing use. CCS is a technology-driven activity that requires capturing carbon dioxide produced by industrial activity; transporting it; and then storing it deep underground.

Afforestation and CCS are the only most effective ways of reducing atmospheric CO2.

More than 190 countries have signed the Paris Agreement designed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Even with pledges of massive reductions in emissions, however, many scientists believe carbon removal technologies would be needed to meet the goal.

Without a firm action to deliver 1 Gigatonne (Gt) of negative emissions globally by 2025, keeping global warming within the Paris Agreement target of 1.5°C cannot be achieved, according to a report by Coalition for Negative Emissions (CNE) published June 2021.

The current cost of carbon removal is around $900-1000 a tonne of CO2. Currently, only one mega-scale project is commissioned in Iceland, which now houses the world’s largest CCS plant that aims to capture about 4,000 tonnes of CO2 every year viz 0.036 Mt by 2030.

So, the world needs 50,000 such CCS plants by 2024-25 to achieve a one-Gt reduction. This is in addition to addressing the new emissions that are likely to increase with post-novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) revival plans.

The massive afforestation programme set up by the Government of Telangana in India — which aims to plant 2.3 billion samplings with a target sustaining rate of 60 per cent — will absorb at least 46 Mt by 2030. Yet, the net removal of CO2 is likely to be around 1.9 Mt by 2030.

But MAA is difficult to execute in a sustained manner given the pressure of population, jobs and wealth distribution. But technological interventions like CCS are the only solution that can be adopted for countries to meet the target and eventually become net-zero.

A few European countries and China have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050 and 2060 respectively. For them to meet the target, the carbon absorption should be in the range of 0.3-1 Bt of CO2 per annum, according to Arunabha Ghosh, chief executive, Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The math seems simple but given the cost and the disturbed economies in the post-pandemic world, the funding of such projects is a billion-dollar question.

Let us try to devise a conceptual strategy to source the funds. Luckily, most developed cities are near the coasts and are the most vulnerable to climate change.

These cities may put restrictions on the products or services that are not responding to climate change by way of direct action, which will put pressure on the companies to start making provisions in their budgets and start investing in the CCS projects.

The economically underdeveloped states also need to start preparing an action plan for CO2 removal by way of MAA parallelly devising plans to penalise the companies.

But then not all the companies are large enough to set up or directly invest in CCS and need a market to indirectly contribute to CCS by paying a price, a market for carbon credits already exists but with discriminative pricing. Such pricing is detrimental in convincing the companies and states to invest in such projects.

The current market needs to facilitate trade of carbon credits, which are generated by reducing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. A new market or a new mechanism for trade of such carbon credits with a flat price mechanism for the initial 10 years and mandatory purchase of the same by each country with a defined quota should be developed.

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth

The cost of failure is astronomical. Studies have shown that the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius can mean the submersion of small island states, the death of coral reefs, extreme heat waves, flooding and wildfires and pervasive crop failure.

That translates into many premature deaths, more mass migration, major economic losses, large swaths of unlivable land and violent conflict over resources and food — what the UN secretary-general has called “a hellish future.”

[Get The Conversation’s most important politics headlines, in our Politics Weekly newsletter.]

Shelley Inglis, Executive Director, University of Dayton Human Rights Center, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UNEP production gap report: Net-zero targets by countries are empty pledges without plans

Governments are planning to produce more than double the production of fossil fuels than what the world requires to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius

By Samrat Sengupta

Published: Wednesday 20 October 2021

The climate crisis has become clearer than ever, but it has not been able to compel major emitters to improve action on the ground so far. Governments across the world are still planning to produce more than double the fossil fuels than what the world requires to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

This was flagged by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report released October 20, 2021.

The production gap to achieve the climate goal is the widest for coal: Production plans and projections by governments would lead to around 240 per cent more coal, 57 per cent more oil, and 71 per cent more gas in 2030 than global levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.

The modelling analysis has considered carbon dioxides removal (CDR) technologies to be deployed widely and methane emissions and leakages to be arrested. These assumptions are yet to be proven workable in practice and any deviation from the assumptions will lead to further widening of the gap.

Global fossil fuel production under four pathways from 2019 to 2040, denominated in extraction-based CO2 emissions in units of billion tonnes of CO2 per year (GtCO2/yr). This reflects the amount of CO2 emissions expected to be released from the combustion of extracted coal, oil, and gas. Source: Production Gap Report 2021, UNEP

The most worrying factor is that almost all major coal, oil and gas producers are planning to increase their production till at least 2030 or beyond.

This has been fuelled by incremental capital flow towards fossil fuels in comparison to clean energy in the post novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) recovery phase. The Group of 20 countries has channelised $300 billion to fossil fuels since the beginning of the pandemic, and the sector is still enjoying significant fiscal incentives.

The world does not have any more time to alter its trajectory of energy use from fossil to clean energy, and a slight deviation in the coming decade will have a substantial burden of adversaries to our future generations, as we will be locked into long-term human-induced global warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius.

The world leaders have planned to meet during the first half of November 2021, at the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Glasgow, United Kingdom, to negotiate on pathways to avert this crisis.

The report has underlined massive gaps between our pledges and actions, which need to be rectified with a real policy plan and finance.

Why we must ponder on carbon capture technology to reduce GHG emissions

CCS is a technology-driven activity that requires capturing carbon dioxide produced by industrial activity, transporting it, and storing it deep underground

By Siddartha Ramakanth Keshavadasu

CCS is a technology-driven activity that requires capturing carbon dioxide produced by industrial activity, transporting it, and storing it deep underground

By Siddartha Ramakanth Keshavadasu

Published: Monday 18 October 2021

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a potent greenhouse gas. It is abundant and stays in the atmosphere for a long time. It is responsible for about 66 per cent the total energy imbalance that has been causing the Earth’s temperature to rise.

It also dissolves in the ocean water, producing carbonic acid and lowering the ocean’s pH. This adversely affects the marine life. CO2 is one of the most notorious gases contributing to the changing climate.

To achieve the results pledged under Paris Agreement, 2015 to limit future temperature increases to 1.5 degree Celsius, emission reduction may just not be sufficient.

Literal removal of carbon from the atmosphere is vital to achieve the target, without which the cascade effect will result in catastrophic events, including sinking of the world’s important cities. It will pose risks to roads, railways, ports, underwater internet cables, farmland, sanitation and drinking water pipelines and reservoirs as well as even mass transit systems.

Some cities will disappear from the world map; others will need to become resilient to this change. Around 90 per cent of all coastal areas will be affected to varying degrees, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Risk Report.

To address the risks, we need to deploy technologies to remove carbon from the atmosphere apart in addition to reducing emissions. Mass and Aggressive Afforestation (MAA) and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) are the primary ways of doing it.

MAA is more of a natural process, which also requires land recovery from existing use. CCS is a technology-driven activity that requires capturing carbon dioxide produced by industrial activity; transporting it; and then storing it deep underground.

Afforestation and CCS are the only most effective ways of reducing atmospheric CO2.

More than 190 countries have signed the Paris Agreement designed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Even with pledges of massive reductions in emissions, however, many scientists believe carbon removal technologies would be needed to meet the goal.

Without a firm action to deliver 1 Gigatonne (Gt) of negative emissions globally by 2025, keeping global warming within the Paris Agreement target of 1.5°C cannot be achieved, according to a report by Coalition for Negative Emissions (CNE) published June 2021.

The current cost of carbon removal is around $900-1000 a tonne of CO2. Currently, only one mega-scale project is commissioned in Iceland, which now houses the world’s largest CCS plant that aims to capture about 4,000 tonnes of CO2 every year viz 0.036 Mt by 2030.

So, the world needs 50,000 such CCS plants by 2024-25 to achieve a one-Gt reduction. This is in addition to addressing the new emissions that are likely to increase with post-novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) revival plans.

The massive afforestation programme set up by the Government of Telangana in India — which aims to plant 2.3 billion samplings with a target sustaining rate of 60 per cent — will absorb at least 46 Mt by 2030. Yet, the net removal of CO2 is likely to be around 1.9 Mt by 2030.

But MAA is difficult to execute in a sustained manner given the pressure of population, jobs and wealth distribution. But technological interventions like CCS are the only solution that can be adopted for countries to meet the target and eventually become net-zero.

A few European countries and China have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050 and 2060 respectively. For them to meet the target, the carbon absorption should be in the range of 0.3-1 Bt of CO2 per annum, according to Arunabha Ghosh, chief executive, Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The math seems simple but given the cost and the disturbed economies in the post-pandemic world, the funding of such projects is a billion-dollar question.

Let us try to devise a conceptual strategy to source the funds. Luckily, most developed cities are near the coasts and are the most vulnerable to climate change.

These cities may put restrictions on the products or services that are not responding to climate change by way of direct action, which will put pressure on the companies to start making provisions in their budgets and start investing in the CCS projects.

The economically underdeveloped states also need to start preparing an action plan for CO2 removal by way of MAA parallelly devising plans to penalise the companies.

But then not all the companies are large enough to set up or directly invest in CCS and need a market to indirectly contribute to CCS by paying a price, a market for carbon credits already exists but with discriminative pricing. Such pricing is detrimental in convincing the companies and states to invest in such projects.

The current market needs to facilitate trade of carbon credits, which are generated by reducing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. A new market or a new mechanism for trade of such carbon credits with a flat price mechanism for the initial 10 years and mandatory purchase of the same by each country with a defined quota should be developed.

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth

Erin Hooley/Chicago Tribune/TNS

Erin Hooley/Chicago Tribune/TNS