Canada should limit use of forceps in childbirth to prevent lifelong injuries to women: Study

Education about the risks needed for both clinicians and mothers, say University of Alberta experts on incontinence

Peer-Reviewed PublicationCanada has an alarmingly high rate of forceps use during childbirth and a correspondingly high number of preventable injuries to mothers, according to recently published research from an international team of incontinence experts.

The researchers call for a reduction in the number of births by forceps in Canada and better education for both clinicians and mothers on how to avoid injury when forceps are required.

“Often women who have had this type of delivery are completely shell-shocked because they’ve got infection, they’ve got pain, they’ve got a newborn and they had no idea that this was even a possibility,” said co-principal investigator Jane Schulz, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

“Education is needed for both patients and health providers that this is a potential complication,” said Schulz, who is also a urogynecologist with the pelvic floor clinic at the Lois Hole Hospital for Women and the Alberta Women’s Health Foundation Chair in Women’s Health Research.

The injuries can lead to immediate or long-term complications including poor healing, infection, chronic pain, sexual dysfunction, bladder or bowel incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

“These birth injuries sometimes result in conditions which are extremely troublesome in later life,” said co-principal investigator Adrian Wagg, division director of geriatric medicine and scientific director for the AHS Seniors’ Health Strategic Clinical Network.

“This is a call to action for Canadian providers in terms of quality improvement,” said Wagg, who is also Alberta Health Services Endowed Professor of Healthy Ageing and professor of continence sciences at the University of Gothenburg.

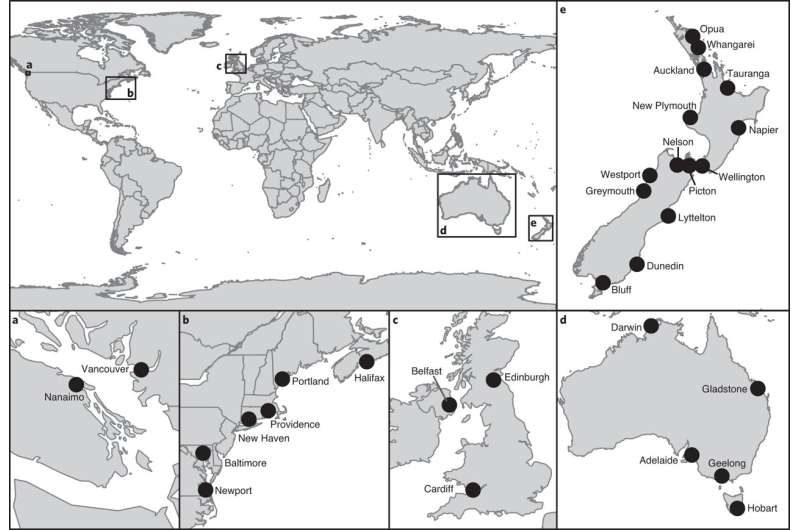

The researchers analyzed nearly two million birth records from Canada, Norway, Sweden and Austria, focusing on women who were giving birth for the first time or had a vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC).

Overall, five per cent of the women had third or fourth degree tears to the perineum — the area between the vagina and the anus. Canada and Sweden had the highest rates of injury, and Austria and Norway the lowest.

The injuries were associated with the use of instruments — either a vacuum or forceps — during delivery. About one in four pregnancies was delivered using instruments in both Canada and Norway in 2016, but the researchers found that Canadian women had a much higher rate of injury: 24.3 per cent of the Canadian mothers with forceps deliveries were injured, compared with 6.2 per cent in Norway.

“We’re not doing well compared to other countries that were chosen based on similar social demographics and health-care services,” Schulz said.

Schulz explained that the forceps can cause either mechanical or neurological trauma to the pelvic floor of the mother.

“They are kind of like large sugar tongs. You put them on the baby’s head and pull the baby out,” she said. “The blades go around the baby’s head and can potentially tear muscles and ligaments of the pelvic floor or cause damage to the nerves that supply the pelvic floor.”

Norway introduced a perineal protection program in 2004 that has led to a sharp decline in injuries. Physicians, midwives and nurses are taught techniques to prevent perineal damage, such as how to slow down the second stage of delivery when the infant’s head is crowning, how to avoid pushing during crowning and when to perform an episiotomy (a surgical cut to the perineum to prevent tearing).

“They also have education around how to recognize an injury, repair it, make sure antibiotics are given and then follow up to ensure it has healed,” said Schulz.

Schulz noted that some women are at higher risk of injury during childbirth due to factors such as having a larger baby or a shorter perineum.

Schulz and Wagg said they intend to work with obstetrical health providers, potentially through groups such as the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, to improve education for clinicians and provide better information for new mothers.

“Obstetrical care providers go through a checklist of things at prenatal visits including nutrition, genetic screening options, vaccinations and routine prenatal testing, but this is often something that is not discussed, so patients are unaware,” said Schulz.

“I advocate for women to be fully informed about their options in childbirth and counsel women to avoid forceps if at all possible,” said Wagg. “Caesarean section is the fallback option, although of course we know there are other concerns about the health of the infant (such as immune changes), so it’s important to discuss beforehand.”

In an earlier study, Schulz reported on how the perineal clinic in Edmonton, started in 2011, helps women injured in childbirth. Patients are seen within six weeks of delivery so they can be assessed and treated by a team of physicians, nurses and physiotherapists. A team of researchers and clinicians with diverse specialties including geriatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and urology continues to look for ways to enhance care for patients with pelvic floor problems.

Both Wagg and Schulz are members of the Women and Children’s Research Health Institute. The study was funded by the Gothenburg Continence Research Centre, of which Wagg is co-director.

Wagg noted that one in four Canadian women over the age of 65 has a bladder problem and a quarter of them inaccurately believe it’s normal to be incontinent just because they are getting older — which may prevent them from seeking medical help for what may be the result of an injury.

“We see this as a real opportunity to improve the quality of care for Canadian women,” he said.

###

JOURNAL

Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica

ARTICLE TITLE

Temporal trends in obstetric anal sphincter injury from the first vaginal delivery in Austria, Canada, Norway, and Sweden

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

25-Aug-2021