Global deforestation deal will fail if countries like Australia don't lift their game on land clearing

At the Glasgow COP26 climate talks overnight, Australia and 123 other countries signed an agreement promising to end deforestation by 2030.

The declaration's signatories, which include global deforestation hotspots such as Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have committed to "working collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation."

This declaration should be welcomed for recognizing how crucial forest loss and land degradation are to addressing climate change, biodiversity decline and sustainable development.

But there have been many such declarations before, and it's hard to feel excited about yet another one.

What really matters is changing policy domestically; if countries don't change what they are doing at home to bring emissions from fossil fuels to zero and restore degraded lands, declarations like this are meaningless.

The good parts

The declaration does a good job of joining up interrelated issues that for too long have been treated as separate problems.

Signatories say they will "emphasize the critical and interdependent roles of forests of all types, biodiversity and sustainable land use in enabling the world to meet its sustainable development goals; to help achieve a balance between anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and removal by sinks; to adapt to climate change; and to maintain other ecosystem services."

Biodiversity is key to forest conservation and sustainable land use.

From there, the signatories promise to "reaffirm our respective commitments, collective and individual, to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, the Sustainable Development Goals; and other relevant initiatives."

To see commitments under several UN declarations recognized in one place is somewhat of a breakthrough; forests, biodiversity and land-use are often siloed despite the critical links in dealing with these issues.

It is also promising to see recognition that conserving existing forests and other terrestrial ecosystems is the priority, and signatories committing to accelerate their restoration (as opposed to just planting new trees).

A vast body of research shows planting new trees as a climate action pales in comparison to protecting existing forests. As I have written before, "restoring degraded forests and expanding them by 350 million hectares will store a comparable amount of carbon as 900 million hectares of new trees […] Forest ecosystems (including the soil) store more carbon than the atmosphere. Their loss would trigger emissions that would exceed the remaining carbon budget for limiting global warming to less than the 2℃ above pre-industrial levels, let alone 1.5℃, threshold."

Once intact forests are gone, we can't regain the carbon lost. It is known as "irrecoverable carbon". So protecting existing forests is the top priority, especially given the critical time frame we are in now to keep climate change under the 1.5℃ or even 2℃ thresholds.

The declaration also mentions trade, promising to "facilitate trade and development policies, internationally and domestically, that promote sustainable development, and sustainable commodity production and consumption, that work to countries' mutual benefit, and that do not drive deforestation and land degradation"

Here, we are starting to get to the real drivers of deforestation. For a long time, there has been too much focus on local drivers of deforestation including local communities. But research shows the leading drivers of deforestation are internationally traded agricultural commodities such as beef, soy, palm oil and timber.

The overall rate of commodity-driven deforestation has not declined since 2001. We can't tackle forest loss without tackling the trade drivers behind it.

The not-so-good parts

The main deficiency in the text is that not enough attention is paid to the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

It is mentioned the countries will "recognize" and "support" the rights of Indigenous peoples but many of these signatories do not have adequate—or, in some cases, any—legislation that actually recognizes those rights.

Subjugation of these rights to national law has been a problem in previous international agreements.

The challenge in many countries is regulatory reform to bring national recognition of land, tenure and other collective rights into line with the internationally recognized rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The track records of some of these signatories bring into question what policy change they will be making back home to ensure this declaration isn't just for show.

As a global land clearing hotspot, Australia will need to enact rapid policy change to bring its current practices in line with what it has signed on to. Australia remains the only developed nation on the list of global deforestation fronts. This is due to weakening land clearing legislation in New South Wales and Queensland, mostly for expansion of grazing lands.

As a signatory to this new declaration, Australia must strengthen land clearing laws, end native forest logging, and restore degraded ecosystems—just planting new trees will not get us there. Australia has the potential to restore large areas of degraded land. Experts have proposed how this could be done for relatively little investment.

The European Union has signed on too; it has been a global leader on developing trade policies designed to end illegal logging and reduce deforestation. But it recently backpedaled on its commitment to a program of forest governance and law enforcement in timber-producing countries that allow access to the EU timber market.

If they are serious about this declaration, the EU must reaffirm its commitment to partner countries to address illegal logging in traded timber.

In Brazil, the Bolsonaro government has been winding back previous legislation to recognize Indigenous peoples' land rights. Deforestation rates have soared in the past few years. Perhaps the first action Brazil could take as a signatory to this declaration is to prioritize the landmark case (currently on hold) before Brazil's Supreme Court to protect Indigenous land rights.

Ending deforestation and restoring forests is not enough

This is the latest in a series of similar declarations. A pledge made at COP24 in Katowice, the New York Declaration on Forests, and Sustainable Development Goal 15 (Life on Land) all include similar commitments to end deforestation by 2030 or earlier.

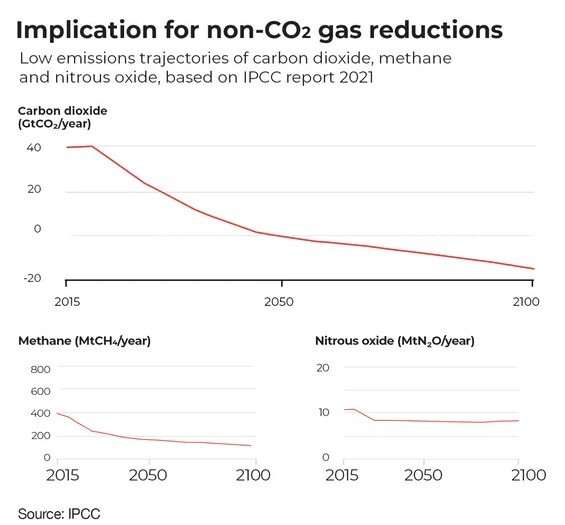

This week's COP26 declaration ends with the importance of "pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5℃, noting that the science shows further acceleration of efforts is needed if we are to collectively keep 1.5℃ within reach."

The fact is, we won't achieve this through ending deforestation and restoring forests. These efforts are critically needed to address biodiversity loss and rural sustainability, but for limiting warming to 1.5℃, fossil fuel emissions need to come down to zero—nowWhy COP26 agreement will struggle to reverse global forest loss by 2030

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Why COP26 agreement will struggle to reverse global forest loss by 2030

More than 100 world leaders meeting at COP26—the UN climate summit in Glasgow—have committed to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030.

The countries that have signed the agreement contain 85% of the world's forests. The announcement includes £14 billion (US$19.2 billion) of public and private funds for conservation efforts. In addition, 28 countries have committed to ensuring trade in globally important commodities such as palm oil, cocoa and soy, does not contribute to deforestation.

Saving the world's dwindling forests is essential if we are to avoid dangerous climate change. Forests soak up carbon from the atmosphere and cutting them down releases it. On balance, forests removed about 7.6 billion tons of carbon every year over the last two decades. This is roughly 15% of global emissions.

But forests around the world are moving from net sinks of carbon, which soak up more than they release, to net sources. While the Amazon rainforest as a whole remains a carbon sink (for now), ongoing land clearance in parts of the Brazilian Amazon mean forests there are already emitting more carbon than they absorb. Increasing global temperatures are causing more forest fires too, further raising emissions from forests and so driving global temperatures higher.

Given that the window for keeping global warming below 1.5°C, or even 2°C, is rapidly closing, humanity desperately needs remaining forests to stay standing. So is the Glasgow leaders' declaration on forests and land use up to the task?

Past failures

This is only the most recent commitment to stop forest loss in a series of similar initiatives. Back in 2005, the UN Forum on Forests committed to "reverse the loss of forest cover worldwide" by 2015. In 2008, 67 countries pledged to try and reach zero net deforestation by 2020. This was followed by the New York declaration on forests in 2014 which saw 200 countries, civil society groups and indigenous peoples' organizations commit to halve deforestation by 2020 and end it by 2030.

These earlier efforts clearly failed to meet their targets. On average, rates of forest loss have been 41% higher in the years since the New York agreement was signed. It's almost impossible to know what deforestation rates would have been without these pledges.

It is important not to vilify those clearing tropical forests. In most cases, whether it's oil-palm plantation workers in southeast Asia, or the owner of a family-run cocoa farm in Ghana, these are just ordinary people trying to make a living. Where those clearing forest are poor subsistence farmers with few alternatives, such as many in Madagascar for example, preventing forest clearance can mean some of the poorest people on the planet are bearing the cost of tackling climate change. Given that such people contribute relatively few emissions, this isn't very fair.

What we do know is that progress on slowing deforestation has been wildly inadequate. The good news is Brazil, Russia and China, who did not sign the 2014 declaration, have this time. However, words are cheap, actually slowing deforestation is difficult to achieve.

Why is it so hard to slow deforestation?

The causes of forest loss vary from place to place, but the problem boils down to a conflict between those who benefit from deforestation and those who benefit from keeping forests intact, and whose ability to influence what happens on the ground wins out.

Conserving forests benefits everybody by stabilizing the climate. But logging, or clearing a patch of forest for farming, benefits the people involved in a much more direct and tangible way. Ultimately, to keep forests intact, those who benefit from forests (that's all of us) need to fund efforts to conserve them.

Despite criticism, and problems with implementation, this is the underlying rationale to REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) – the UN mechanism whereby tropical nations are paid for efforts to conserve forests.

Just before flying to Glasgow, Madagascar's minister of environment and sustainable development, Dr. Baomiavotse Vahinala Raharinirina, visited a village to ask people their views on what would make forest conservation more effective. They spoke about the lack of alternative livelihoods, the need for more support to help them manage the forest sustainably, and the fact that local communities often lack the ability to exclude those who wish to exploit forests.

Raharinirina said: "Madagascar has contributed relatively little to climate change, but our people are suffering the consequences. For example, a million people in the south are in need of food aid because of the effects of a drought caused by climate change. We are trying to do our bit to reduce emissions by conserving and restoring our forests and have signed the Glasgow Leaders Declaration, however this won't be achieved without more resources… We will need support from the international community to help us achieve this."

I am cautiously impressed with how much attention is being paid to the question of fairly reducing tropical deforestation at COP26. The first event in the UK-led program brought forest communities and indigenous people together to discuss lessons from the last decade of forest conservation.

Dolores de Jesus Cabnal Coc, an indigenous leader from Guatemala, shared my cautious optimism, saying: "It's a slow process and will continue to be, but ever since [COP21 in Paris in 2015] there has been a big difference in that there is now a platform to help ensure more inclusive actions…"

Perhaps I am naive, but I sense a helpful change in tone among world leaders, from assuming that forest conservation inevitably delivers triple wins which benefit the climate, biodiversity and local livelihoods, to a more honest acknowledgement that often, there are winners and losers. Only by finding ways for conservation to benefit those who live alongside forests can the world hope to keep those forests absorbing emissions for years to come.

So, will this pledge finally halt and reverse deforestation? Unlikely. But given the importance of the issue, the renewed focus on deforestation at COP26 is certainly positive.Why tackling deforestation is so important for slowing climate change

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()