“Cold Bone”: New Dinosaur Species Discovered That Lived on Greenland 214 Million Years Ago

Living reconstruction of Issi saaneq, a newly discovered dinosaur that lived on Greenland 214 million years ago. Credit: Victor Beccari

The two-legged dinosaur Issi saaneq lived about 214 million years ago in what is now Greenland. It was a medium-sized, long-necked herbivore and a predecessor of the sauropods, the largest land animals ever to live. It was discovered by an international team of researchers from Portugal, Denmark, and Germany, including the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU). The name of the new dinosaur pays tribute to Greenland’s Inuit language and means “cold bone.” The team reports on its discovery in the journal Diversity.

The initial remains of the dinosaur — two well-preserved skulls — were first unearthed in 1994 during an excavation in East Greenland by paleontologists from Harvard University. One of the specimens was originally thought to be from a Plateosaurus, a well-known long-necked dinosaur that lived in Germany, France, and Switzerland during the Triassic Period. Only a few finds from East Greenland have been prepared and thoroughly documented. “It is exciting to discover a close relative of the well-known Plateosaurus, hundreds of which have already been found here in Germany,” says co-author Dr. Oliver Wings from MLU.

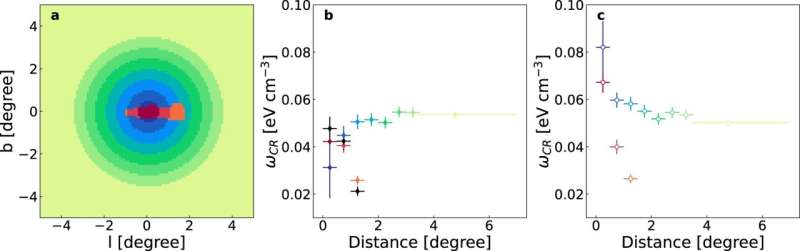

Issi saaneq skulls (holotype on the top, paratype on the bottom). Picture and 3D models after the CT-scan. Credit: Victor Beccari

The team performed a micro-CT scan of the bones, which enabled them to create digital 3D models of the internal structures and the bones still covered by sediment. “The anatomy of the two skulls is unique in many respects, for example in the shape and proportions of the bones. These specimens certainly belong to a new species,” says lead author Victor Beccari, who carried out the analyses at NOVA University Lisbon.

The plant-eating dinosaur Issi saaneq lived around 214 million years ago during the Late Triassic Period. It was at this time that the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart and the Atlantic Ocean began forming. “At the time, the Earth was experiencing climate changes that enabled the first plant-eating dinosaurs to reach Europe and beyond,” explains Professor Lars Clemmensen from the University of Copenhagen.

The two skulls of the new species come from a juvenile and an almost adult individual. Apart from the size, the differences in bone structure are minor and only relate to proportions. The new Greenlandic dinosaur differs from all other sauropodomorphs discovered so far, however it does have similarities with dinosaurs found in Brazil, such as the Macrocollum and Unaysaurus, which are almost 15 million years older. Together with the Plateosaurus from Germany, they form the group of plateosaurids: relatively graceful bipeds that reached lengths of 3 to 10 meters.

The new findings are the first evidence of a distinct Greenlandic dinosaur species, which not only adds to the diverse range of dinosaurs from the Late Triassic (235-201 million years ago) but also allows us to better understand the evolutionary pathways and timeline of the iconic group of sauropods that inhabited the Earth for nearly 150 million years.

Once the scientific work is completed, the fossils will be transferred to the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Reference: “Issi saaneq gen. et sp. nov.—A New Sauropodomorph Dinosaur from the Late Triassic (Norian) of Jameson Land, Central East Greenland” by Victor Beccari, Octávio Mateus, Oliver Wings, Jesper Milàn and Lars B. Clemmensen, 3 November 2021, Diversity.

DOI: 10.3390/d13110561

New species of iguanodontian dinosaur discovered from Isle of Wight

IMAGE: RECONSTRUCTION OF THE HEAD OF BRIGHSTONEUS SIMMONDSI view more

CREDIT: CREDIT TO JOHN SIBBICK

- Natural History Museum and University of Portsmouth scientists describe new species of dinosaur

- Discoveries of iguanodontian dinosaurs from the Isle of Wight have previously only been assigned to Iguanodon or Mantellisaurus

- Diversity of dinosaurs in the Early Cretaceous of the UK is much greater than previously thought

Scientists from the Natural History Museum and University of Portsmouth have described a new genus and species of dinosaur from a specimen found on the Isle of Wight.

Following on from a new species of ankylosaur, new species of therapod and two new species of spinosaur dinosaurs, Brighstoneus simmondsi is the latest in a host of new dinosaur species described by Museum scientists in recent weeks.

The new dinosaur is an iguanodontian, a group that also includes the iconic Iguanodon and Mantellisaurus. Until now, iguanodontian material found from the Wealden Group (representing part of the Early Cretaceous period) on the Isle of Wight has usually been referred to as one of these two dinosaurs – with more gracile fossil bones assigned to Mantellisaurus and the larger and more robust material assigned to Iguanodon.

However, when Dr Jeremy Lockwood - a PhD student at the Museum and University of Portsmouth - was examining the specimen, he came across several unique traits that distinguished it from either of these other dinosaurs.

'For me, the number of teeth was a sign’ Dr Lockwood says. ‘Mantellisaurus has 23 or 24, but this has 28. It also had a bulbous nose, whereas the other species have very straight noses. Altogether, these and other small differences made it very obviously a new species.'

The herbivorous dinosaur was about eight metres in length and weighed about 900kg. Published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, Dr Lockwood describes the species and names it Brighstoneus simmondsi: Brighstoneus after the village of Brighstone, near to the excavation site, and simmondsi honouring Mr Keith Simmonds, who made the discovery of the specimen in 1978.

The discovery of this new species suggests that there were far more iguanodontian dinosaurs in the Early Cretaceous of the UK than previously thought, and that simply assigning specimens from this period to either Iguanodon or Mantellisaurus must change.

'We're looking at six, maybe seven million years of deposits, and I think the genus lengths have been overestimated in the past, ‘says Dr Lockwood. ‘If that's the case on the island, we could be seeing many more new species. It seems so unlikely to just have two animals being exactly the same for millions of years without change.’

Museum scientist Dr Susannah Maidment, a co-author of the paper, says: ‘The describing of this new species shows that there is clearly a greater diversity of iguanodontian dinosaurs in the Early Cretaceous of the UK than previously realised. It’s also showing that the century-old paradigm that gracile iguanodontian bones found on the island belong to Mantellisaurus and large elements belong to Iguanodon can no longer be substantiated’.

The Isle of Wight has long been associated with dinosaur discovery, and even yielded the crucial specimens that led to Sir Richard Owen to coin the term Dinosauria. The authors conclude that the describing of Brighstoneus simmondsi as a new species calls for a reassessment of Isle of Wight material:

'British dinosaurs are certainly not something that's done and dusted at all,’ says Dr Lockwood. ‘I think we could be on to a bit of a renaissance.'

###

The study A new hadrosauriform dinosaur from the Wessex Formation, Wealden Group (Early Cretaceous), of the Isle of Wight, Southern England is published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

JOURNAL

Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Animals

ARTICLE TITLE

A new hadrosauriform dinosaur from the Wessex Formation, Wealden Group (Early Cretaceous), of the Isle of Wight, Southern England

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

11-Nov-2021

Tooth fast, tooth curious?

IMAGE: LONG NECK, LONG TAIL, TINY HEAD, TINY TEETH. THESE ICONIC, GARGANTUAN DINOSAURS DEVELOPED A WHOLLY UNIQUE DINING STRATEGY TO SUPPORT THEIR MASSIVE SIZE. view more

CREDIT: IMAGE BY STEPHANIE ABRAMOWICZ, COURTESY OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY (NHM).

Los Angeles, CA (November 10, 2021) – How did the largest animals to ever walk the Earth dominate their environments? By doing something totally revolutionary: keeping it simple. Published in BMC Ecology and Evolution, a new study led by Postdoctoral Research Scientist and periodic dinosaur dentist Dr. Keegan Melstrom at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s Dinosaur Institute reveals that colossal sauropod dinosaurs, the largest animals to ever walk the Earth, had a strategy for dining on plants unique to long-necked dinosaurs: linking tooth complexity to how fast teeth were replaced.

“In nearly every other animal we look at, the complexity of a tooth relates to the animal’s diet,” says Dr. Melstrom. “Carnivores have simple teeth, herbivores have complex teeth, often with distinct ridges, crests, and cusps for processing plant material. But sauropods break this incredibly consistent pattern. Instead, these dinosaurs link complexity to tooth replacement rate, with simple teeth being replaced every few weeks!”

The shapes of an animal’s teeth are thought to reveal a lot about its diet and by extension its lifestyle. The banana-sized knives ringing the mouths of T. Rex are perfect for ripping flesh, and deadly simple sharp teeth abound in living and extinct carnivores. Typically, herbivores have extremely complex teeth: perfect for grinding down fibrous leaves or grasses. When it comes to the largest animals to ever walk the Earth, sauropods chewed their own path. Unlike any other plant-eating animals living or extinct, sauropods rely on quickly replacing their teeth to keep the salad flowing.

CAPTION

Close up of a sauropod skull full of simple teeth. These simple, peglike chompers would be rapidly replaced, a strategy unique among all known herbivores.

CREDIT

Image by Stephanie Abramowicz, courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM).

Keep It Simple, Sauropods

“The diet of extinct dinosaurs was incredibly varied, spanning tiny meat-eaters to massive plant-eaters,” says Dr. Melstrom. “Our research sheds light on the range of adaptations that allowed so many plant-eaters to live alongside one another.”

Using computerized tomography (CT) and microCT scanning, Dr. Melstrom and his colleagues made 3D models of specimens from around the globe, capturing the great diversity of tooth complexity in Late Jurassic dinosaurs.

“This whole project was conducted during the pandemic. Instead of traveling the world to gather data, we relied on researchers who had made their data available to other scientists, as well as the incredible collections here at NHM. I think this project really demonstrates the importance of sharing information, it can lead to new discoveries even during a pandemic,” says Dr. Melstrom.

They converted the toothy hills and valleys of dinosaur teeth into numbers, quantifying tooth complexity between the three groups of dinosaurs: meat-eating theropods, plant-eating ornithischians, and similarly herbivorous sauropods.

What they found was an entirely new evolutionary strategy to handle a plant-based diet 150 million years ago. While meat-eating dinosaurs had sharp simple teeth expected for carnivores, and ornithischians had the more complex teeth similar to herbivores living today, sauropods had very simple teeth, unlike any other known herbivores extinct or living.

In sauropods, they found that the more complex the tooth, the more slowly teeth were replaced, a correlation that demonstrates that tooth replacement rate is related to tooth complexity, unlike any other known animals. More specifically, diplodocoids like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus exhibited incredibly fast replacement rates and simple teeth, possibly allowing them to eat different foods from the other group of sauropods, macronarians like Brachiosaurus, which had more complex teeth.

Simple teeth would have made sense for sauropods’ long necks. Smaller teeth built to be lost weigh less than the tougher teeth of all other herbivores, which helps lighten the skull at the end of those long necks. The peculiar tooth replacement pattern meant these sauropods could focus on plant food other dinosaurs and non-dinosaur plant-eaters passed by.

“Time and time again, the fossil record shows us that there isn’t one solution to evolutionary problems. For sauropods, when it comes to eating tough plants, the simplest solution was the best,” says Dr. Melstrom.

CAPTION

Differing dino teeth. Some sauropods, like Apatosaurus, had simple teeth, more similar to a meat-eater, such as the theropod Allosaurus, than to the small-bodied Nanosaurus, another herbivore.

CREDIT

Image by Dr. Keegan Melstrom, courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM).

About the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County

The Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC) include the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park, La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park, and the William S. Hart Museum in Newhall. They operate under the collective vision to inspire wonder, discovery, and responsibility for our natural and cultural worlds. The museums hold one of the world’s most extensive and valuable collections of natural and cultural history—more than 35 million objects. Using these collections for groundbreaking scientific and historical research, the museums also incorporate them into on- and offsite nature and culture exploration in L.A. neighborhoods, and a slate of community science programs—creating indoor-outdoor visitor experiences that explore the past, present, and future. Visit NHMLAC.ORG for adventure, education, and entertainment opportunities.

CAPTION

A skeletal reconstruction of Fruitadens haagarorum, a diminutive ornithischian. Despite its small size, its tooth reflects the complexity typical in all other herbivores, excepting sauropods.

CREDIT

Silhouette by Stephanie Abramowicz, courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM).

JOURNAL

BMC Ecology and Evolution

ARTICLE TITLE

Exceptionally simple, rapidly replaced teeth in sauropod dinosaurs demonstrate a novel evolutionary strategy for herbivory in Late Jurassic ecosystems

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

6-Nov-2021

The world’s largest ammonite species evolved to reach diameters of 1.5-1.8m around 80 million years ago, possibly to evade predation

IMAGE: THE SPECIMEN WAS COLLECTED IN 1894 NEAR SEPPENRADE. LWL-MUSEUM FOR NATURAL HISTORY, MÜNSTER. PHOTO: CI. SCALE: 100 MM. view more

CREDIT: IFRIM ET AL., 2021, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0 (HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY/4.0/)

The world’s largest ammonite species evolved to reach diameters of 1.5-1.8m around 80 million years ago, possibly to evade predation

###

Article Title: Ontogeny, evolution and palaeogeographic distribution of the world’s largest ammonite Parapuzosia (P.) seppenradensis (Landois, 1895)

Author Countries: Germany, Mexico, U.K.

Funding: CI received grant IF61/10-1 from the German Science Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG) WS received grant STI128/40-1 from the DFG Funding to CI for travel and research in Mexico and for analytics was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Science Foundation). Funding to WS for travel and research in Mexico was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0258510

JOURNAL

PLoS ONE

ARTICLE TITLE

Ontogeny, evolution and palaeogeographic distribution of the world’s largest ammonite Parapuzosia (P.) seppenradensis (Landois, 1895)

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

10-Nov-2021

COI STATEMENT

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.