Architecture Built 1,000 Years Ago to Catch Rain is Being Revived to Save India’s Parched Villages

By Andy Corbley

-Nov 11, 2021

SaraswaT VaruN/CC license

SaraswaT VaruN/CC licenseThey brought access to fresh water for millennia, and existed as long-honored pieces of cultural heritage, and then they were abandoned. Now a new chapter is opening on the stepwells of India.

Modern sewage and irrigation systems made them obsolete, but under the weight of extreme drought, the stepwells of India big and small are being restored for their ancient ingenuity and modern thirst-quenching design.

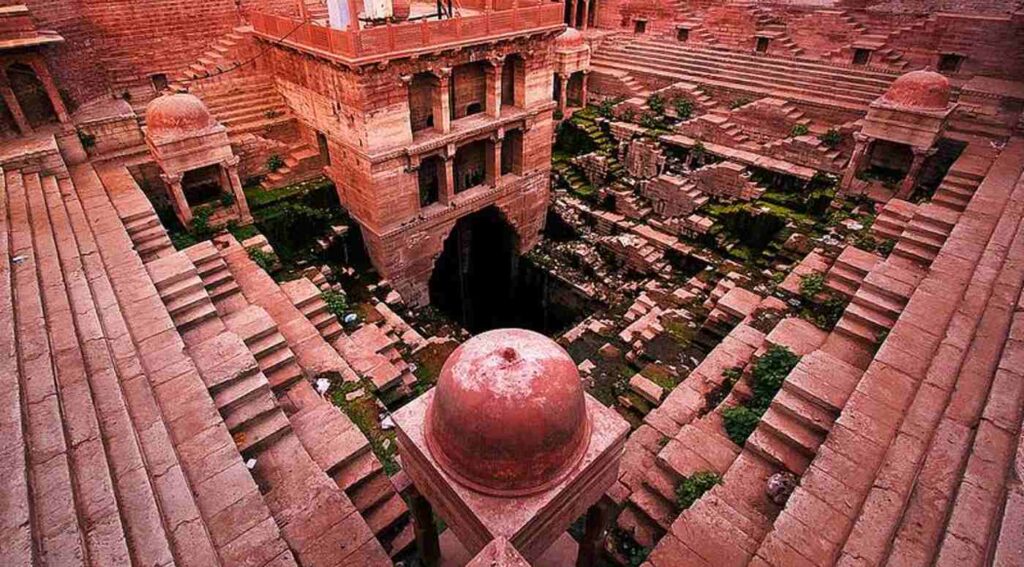

Stepwells are sometimes small stone-lined trenches, capturing rainwater and refilling underground aquafers, while others are masterpieces of inverted architecture, like the Chand Bawri in Rajasthan—a World Heritage Site consisting of the inverse of a step pyramid dug straight into the ground and lined by 3,200 steps set on symmetrical staircases.

However at their core principal, stepwells once restored, still function just as well now as they did in their heyday, and different states in the country are looking to add them to their hydrological arsenal as India faces the worst drought in history.

“It’s ironic that stepwells been ignored, considering how wonderfully efficient they were at providing water for nearly 1,500 years,” said Victoria Lautman, author of the book The Vanishing Stepwells of India. “Now, thanks to the restoration efforts, stepwells will come full circle.”

The stepwells are known as “baolis” or “bwaris” and have not always been conserved as monuments to cherish. Instead, many of India’s more than 3,000 baolis have fallen into disrepair or outright abandonment, being turned instead into dumps or being buried by foliage.

Doron/CC license

“When they began clearing what they thought was a garbage dump, they found the structure of a step-well beneath the garbage,” writes Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, a heritage advocate and writer who works with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture—a non-profit leading the restoration of India’s baolis.

“When they began clearing what they thought was a garbage dump, they found the structure of a step-well beneath the garbage,” writes Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, a heritage advocate and writer who works with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture—a non-profit leading the restoration of India’s baolis.

Pratik.sarode/CC license

“It was one of the deeper stepwells of Delhi. After restoration, the Purana Qila Baoli has so much water that the entire lawns of the [Old Fort in Delhi] are being irrigated by it,” he adds.

MORE: Huge Supply of Water is Saved From Evaporation When Solar Panels Are Built Over Canals

Aga Khan Trust works with stepwells around the country, sandblasting the build up of toxic residue and crumbing material and working with heritage architects for governments interested in repairing the baolis.

“It was one of the deeper stepwells of Delhi. After restoration, the Purana Qila Baoli has so much water that the entire lawns of the [Old Fort in Delhi] are being irrigated by it,” he adds.

MORE: Huge Supply of Water is Saved From Evaporation When Solar Panels Are Built Over Canals

Aga Khan Trust works with stepwells around the country, sandblasting the build up of toxic residue and crumbing material and working with heritage architects for governments interested in repairing the baolis.

Well-wishes

Karnataka/CC license

15 wells have been restored or targeted for restoration in the city of Delhi alone, which will cost less than $60,000, but supply another 33,000 gallons of water to the city. The Toorji stepwell was fixed up in Jodhpur, an old warrior city sitting on the edge of the Thar Desert, which will contribute a staggering 6.2 million gallons.

The Gram Bharati Samiti (Society for Rural Development), a non-profit in the Jaipur district of Rajasthan, has revived seven stepwells in various villages, restoring reliable water access to 25,000 people.

One of those villages was Shivpura, and Rajkumar Sharma, the head teacher of the government primary school there, celebrated the baoli’s return.

“The stepwell in our village was the only source of water. With time, it had dried up and had converted into a heap of rubbish,” he told the BBC. “We now have access to clean water for drinking, domestic use and for religious ceremonies. The baoli has become the grandeur of our village.”

15 wells have been restored or targeted for restoration in the city of Delhi alone, which will cost less than $60,000, but supply another 33,000 gallons of water to the city. The Toorji stepwell was fixed up in Jodhpur, an old warrior city sitting on the edge of the Thar Desert, which will contribute a staggering 6.2 million gallons.

The Gram Bharati Samiti (Society for Rural Development), a non-profit in the Jaipur district of Rajasthan, has revived seven stepwells in various villages, restoring reliable water access to 25,000 people.

One of those villages was Shivpura, and Rajkumar Sharma, the head teacher of the government primary school there, celebrated the baoli’s return.

“The stepwell in our village was the only source of water. With time, it had dried up and had converted into a heap of rubbish,” he told the BBC. “We now have access to clean water for drinking, domestic use and for religious ceremonies. The baoli has become the grandeur of our village.”

Rohan Kale Explorer/CC license

Adding a traditional stepwell to the water provision of a state also revives architectural features of India going back to the Indus Valley Civilization of 2,500 BCE. They generate tourist revenue, and can serve in religious ceremonies, and socially as swimming holes.

RELATED: Man Harvests Water for 10K People in Driest Part of India (WATCH)

Steps lead down to the bottom of the well, which as it’s depleted, continue to allow access to the water below. While the idea of putting a water source on top of what is essentially a pedestrian walkway might seem strange, the stepwells also channel rain into groundwater sources better than rivers, meaning that even if no-one actually draws water out in a bucket, they are still providing water to the community.

CHECK OUT: How India’s Air Pollution is Being Turned into Stylish Floor Tiles

“Stepwells are a repository of India’s historical tales, used for social gatherings and religious ceremonies,” historian Rana Safvi told the BBC. “They served as cool retreats for travelers as the temperature at the bottom was often five-six degrees lesser.” They created a community atmosphere and common space for people as well as providing water. And, says, Safvi, their revival could be a genuine step towards helping India overcome water shortages. That’s hopeful indeed.

Adding a traditional stepwell to the water provision of a state also revives architectural features of India going back to the Indus Valley Civilization of 2,500 BCE. They generate tourist revenue, and can serve in religious ceremonies, and socially as swimming holes.

RELATED: Man Harvests Water for 10K People in Driest Part of India (WATCH)

Steps lead down to the bottom of the well, which as it’s depleted, continue to allow access to the water below. While the idea of putting a water source on top of what is essentially a pedestrian walkway might seem strange, the stepwells also channel rain into groundwater sources better than rivers, meaning that even if no-one actually draws water out in a bucket, they are still providing water to the community.

CHECK OUT: How India’s Air Pollution is Being Turned into Stylish Floor Tiles

“Stepwells are a repository of India’s historical tales, used for social gatherings and religious ceremonies,” historian Rana Safvi told the BBC. “They served as cool retreats for travelers as the temperature at the bottom was often five-six degrees lesser.” They created a community atmosphere and common space for people as well as providing water. And, says, Safvi, their revival could be a genuine step towards helping India overcome water shortages. That’s hopeful indeed.