Douglas Fraser

Business/economy editor, Scotland

The Hindenburg airship tragedy brought a sudden end to the age of the airship

The most common of the elements is seen by some as a magic bullet for next generation energy: by others as an excuse to keep drilling for gas: and by some as a distraction from the real challenge to decarbonise the economy

There are differing opinions on what hydrogen can do best. It could be the fuel that helps the 15% of the economy reckoned to be hard to decarbonise, rather than being for home-heating and cars

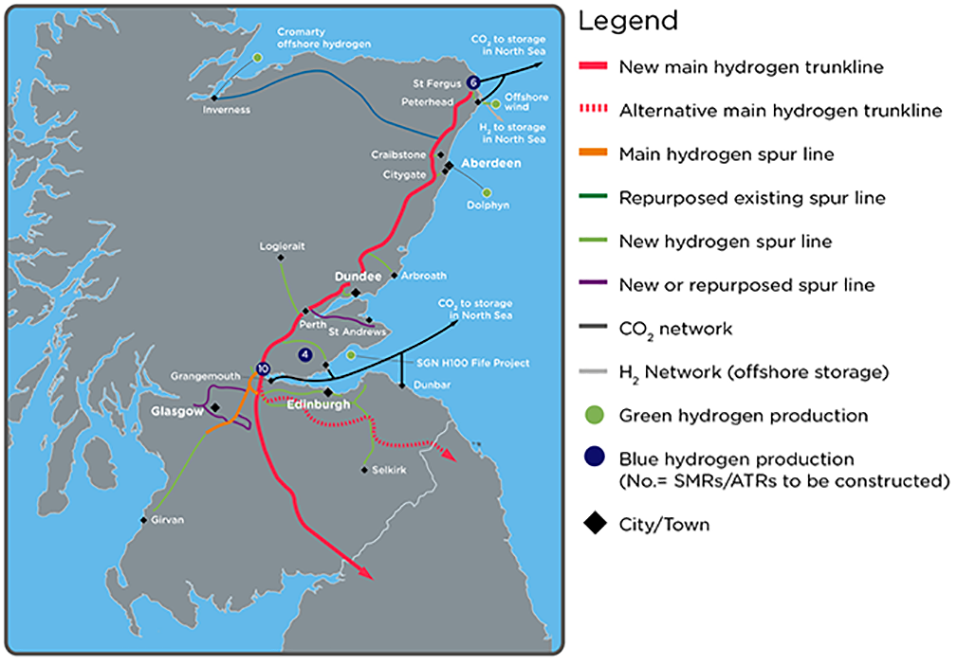

However, the owner of Scotland's gas pipeline network has cooked up an £11.6bn plan to pump hydrogen into most homes and businesses through mostly existing pipes, and using others to gather, capture and banish carbon to a grave far below the North Sea.

The use of hydrogen in transport hit a spectacular snag in May 1937, when the Hindenburg airship caught fire while trying to moor on a high mast in the wake of a New Jersey storm.

As the tragedy gained a lot of media attention, and as people realised that the gas filling those vast and glamorous trans-Atlantic craft was highly flammable, it brought a sudden end to the age of the airship.

But 84 years later, we've learned a bit about air safety, the impact of burning aviation fuel on the environment, and about hydrogen.

So it's back. And this most common of elements is being greeted (by some) as a magic bullet in the great energy transition.

It's very plentiful and recyclable, and the simple chemistry looks attractive. Split water into its two elemental components, with no emissions, then put the hydrogen into a fuel cell and hit the accelerator. Again, no harmful emissions. Only a return to water.

The catch is that electrolysis is expensive, and it is only now heading towards a commercial scale. The young company ITM, based in Sheffield, has taken over a former airfield to build a vast factory.

One of its early orders is from Scottish Power, to install a 10 megawatt unit at the Whitelees wind farm on Eaglesham Moor.

The green hydrogen facility will be based at Whitelee Windfarm in East Renfrewshire

That helps build supply ahead of demand - and in the hope of stimulating demand. At up to four tonnes of hydrogen per day, maximum production from phase one should be sufficient to get buses from Glasgow to Edinburgh, or the return journey, nearly 250 times.

Phase two is expected to be the same scale, and to follow on quickly, at a lower unit cost.

Scottish Power, however, quietly admits it isn't all that interested in buses. It believes they would be better run on batteries.

It sees hydrogen as offering the fuel density and rapid refuelling that is important to shifting heavy loads, especially across long distances. Bin lorries in the city of Glasgow don't travel that far, but they require a lot of energy, they carry a lot of weight, and they are on course to be first customer for Whitelees' green hydrogen.

Energy's chain links

And this is where the question arises for hydrogen. In the words of Edwin Starr: what is it good for?

Heavy goods transport, almost certainly. Maybe shipping. In the coldest climates, where batteries fail. And perhaps fuel-hungry industries.

Keith Anderson, chief executive of Scottish Power, reckons that it could work for much of the 15% or so of the economy that is going to be particularly hard to de-carbonise.

So while ITM would like to see its electrolysis become part of the journey towards hydrogen cars, the utility boss is against that.

Cars have taken the battery route, and hauling them back to restart on a hydrogen future would expose some inefficiencies.

One catch is that the process is not as efficient as others. If you want to fuel a battery with renewable power, that's just what you do.

But with hydrogen, the wind turbine fuels the polymer membrane in ITM's electrolysis stack.

The gas then has to be stored securely and transported to its point of use, at which point it powers a fuel cell, which then operates a battery-electric engine. Each link in that chain comes with a loss of energy.

Keeping on drilling

So in answer to Edwin Starr, perhaps hydrogen is not as big an answer to oil and gas as some would like to think. Indeed, some have hopes that it could be the saving of oil and gas. For its critics, that would be a disaster.

Green activists are concerned that hydrogen is rarely green, through electrolysis, but mostly blue, derived from natural gas. That can be done much more cheaply, and the produce is used across industry, from refining to metals to food processing and NASA's rocket fuel.

Elementary energy: The case for hydrogen

Splitting the gas molecules produces carbon dioxide alongside the hydrogen. Among greenhouse gases, that is the prime suspect for climate change, so a climate-friendly solution has to be carbon capture and storage.

That, in turn, is a very expensive way of solving our climate problems. Indeed, it is proven in theory and in trials, but hasn't yet been proven at a commercial scale.

But it appeals to the hydrocarbon industry, as it allows for continued drilling for natural gas, and production of it, producing a fuel which has a lot more supporters than oil or gas currently do.

Scottish cluster

A further part of the hydrocarbon industry has its own special interest in adopting hydrogen. SGN, owner of the gas pipeline network, is looking into the 2030s and beyond, and wondering if its asset will be getting redundant.

It commissioned Wood, the former oil services group which now does consultancy work on other energy, to look into the Scottish prospects for heating homes through piped hydrogen.

Its report details initial conversion of Aberdeen home energy to reach 100% hydrogen by the end of this decade. At first, it would be 2%, rising as a mix to 20% - currently seen as the highest practical or safe level for a mix - and eventually 100%, making Aberdeen "the world's first hydrogen-powered city".

A lot of that would be blue hydrogen, through the Scottish cluster of businesses wanting to link its production to carbon capture and storage, with a major industrial site around the St Fergus gas terminal, north of the city.

That is where natural gas has long made landfall, and from there, the pipelines stretch offshore with which to banish the treated carbon to subsea storage.

Its failure to win a UK government funding competition has left participants baffled and deeply frustrated.

Greg Hands, the Energy Minister, was at Whitelees wind farm this week, to confirm £9.4m support for the hydrogen project (just under half the total cost), and he told me the two Tier One projects, that did secure backing, were under way already, and that at least four such clusters were envisaged by 2030.

"I don't want to prejudge where the second phase will go," he said,"but I think the Scottish cluster will be in a good position. It clearly passed the eligibility criteria, it did well on the evaluation criteria for the first tier, and has a good chance in the second tier."

Carbon network

Under the SGN/Wood plan, the rest of Scotland's gas network could be converted to hydrogen only 15 years later than the Aberdeen target, in 2045. Wood throws in an extended pipeline network to gather in carbon dioxide from around the country for treatment and storage.

The total cost, at today's prices: £11.6bn. Of that more than £3.4bn is in continued and expanded blue hydrogen generation, and £2.6bn would be required for the green variety, most of that for electrolysis.

Some £1.1bn would prepare the SGN pipeline network for hydrogen, while £500m would buy a gathering network for carbon.

A further £3.3bn would pay for conversion of appliances in homes and business premises.

No-one said it was going to be cheap. But it could bring quality jobs and business opportunities.

It's just one set of ideas, while the alternative - of doing nothing to decarbonise energy use across the economy - isn't a long-term, cheap solution either.