AZoCleantech speaks to Shahar Chaikin from Tel-Aviv University about his latest research on the role of climate change on marine species migration and distribution. This work was also conducted with Ph.D. candidate Shahar Dubiner and Professor Jonathan Belmaker. The team found that the warming climate drives marine species to migrate deeper as the ocean they live in warms.

Can you tell us about your role at

Tel Aviv University?

I am currently a Ph.D. candidate in Professor Jonathan (Yoni) Belmaker’s lab, School of Zoology, The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel-Aviv University.

How did you begin your research into

marine species migration?

As far as I remember myself, I was interested in marine organisms. During my undergraduate studies, I studied seasonal migrations of rays as part of their assumed breeding season. Since then, I began a direct Ph.D. program that allowed me to further expand my study for other marine organisms and explore the potential effects of climate change on species distributions. Together with my supervisor Yoni, we established my Ph.D. dissertation, aimed at elucidating patterns and drivers underlying marine species depth distributions.

What were the key findings of your

recent study on marine animal migration?

We found evidence that an increasingly warming climate may drive marine species such as fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans to compress their depth distributions. This means that their minimum depth limits (i.e., shallow depth limits) are deepening with warming. Furthermore, the amount of deepening is strongly related to species traits. For instance, cold-water species may deepen more than warm-water species.

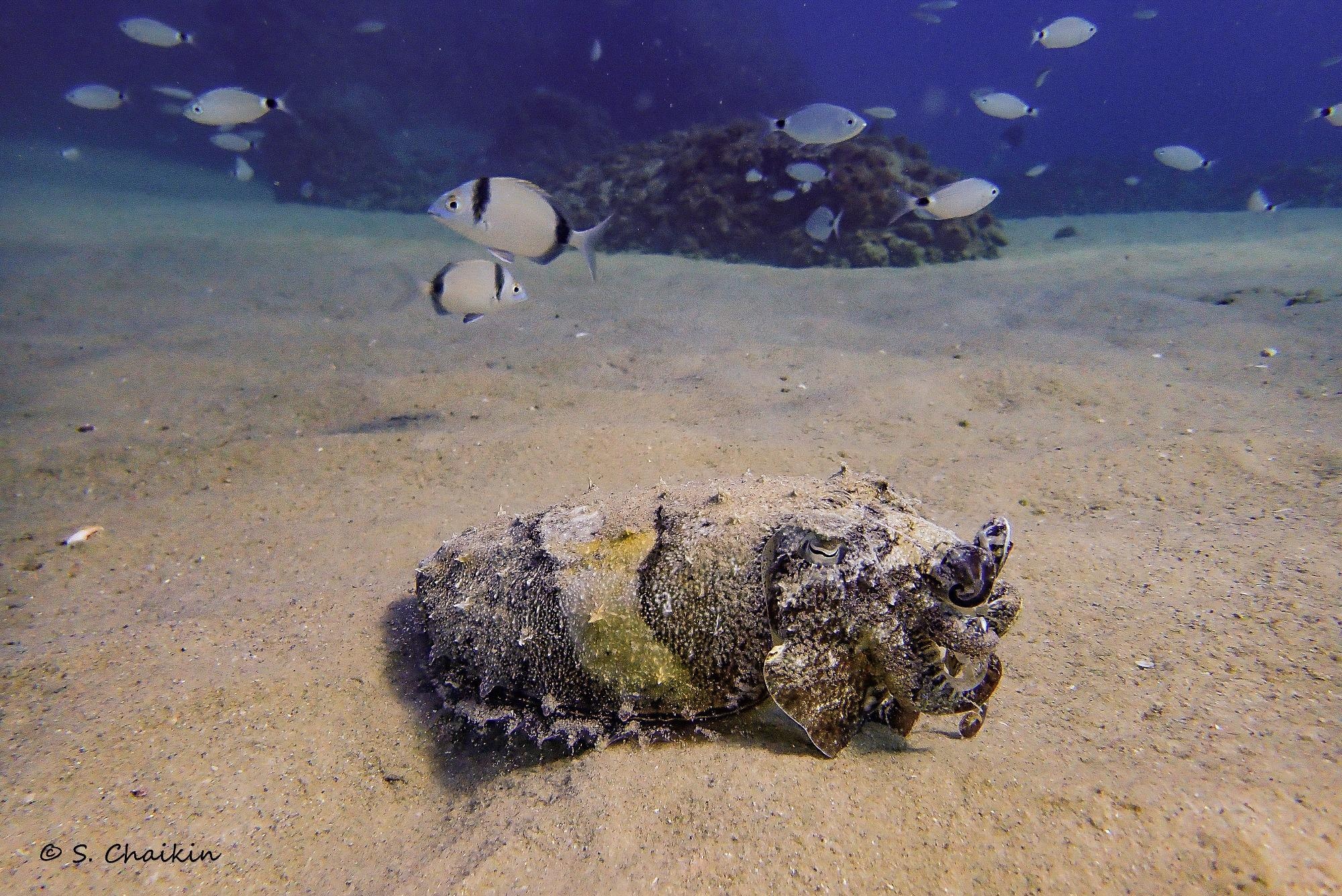

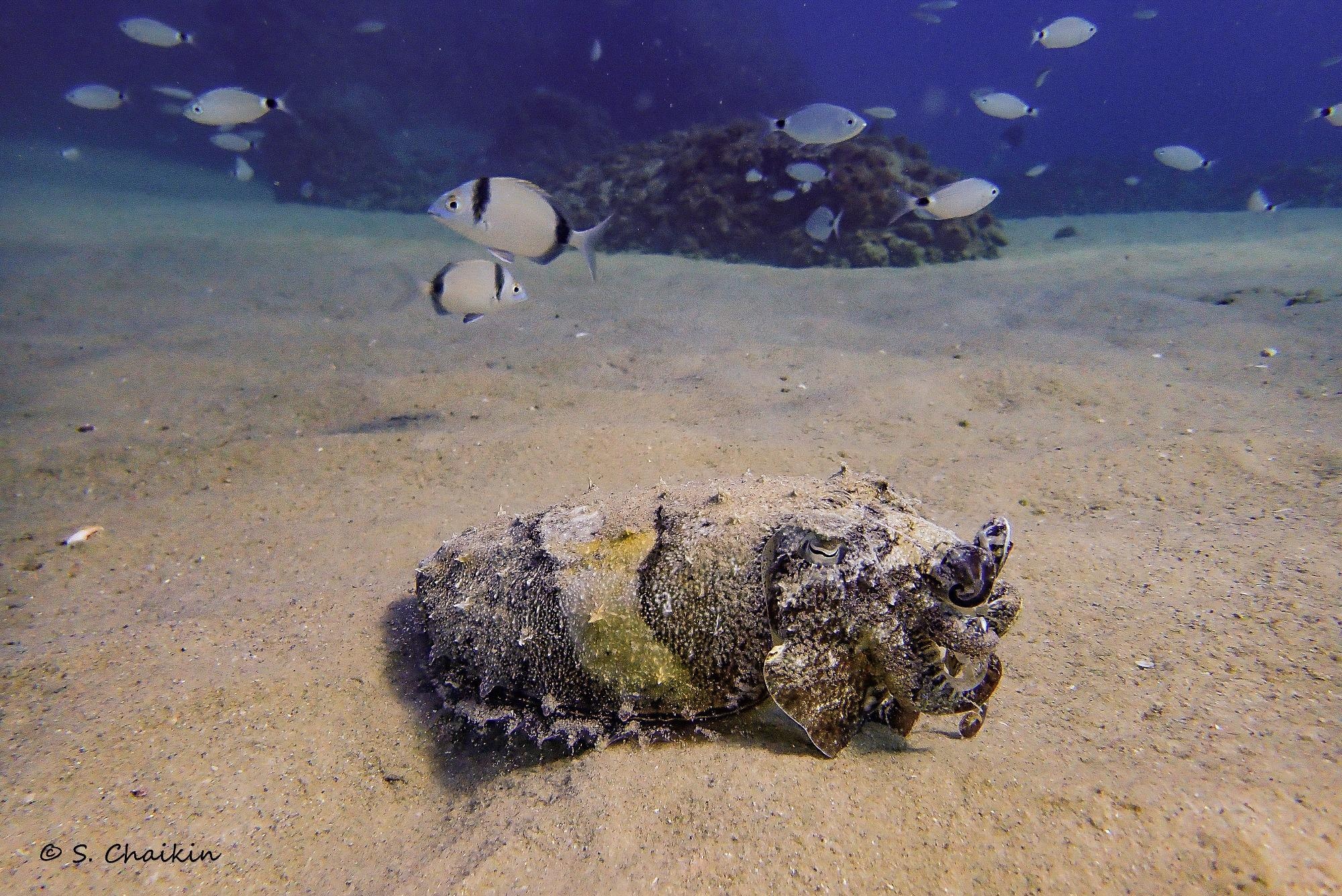

This image of fish and cephalopods was taken on the Israeli coast in the Mediterranean Sea. Image Credit: Shahar Chaikin

Why is understanding marine species behavior important?

The oceans encompass most of our planet and have an important role in supplying vital services for both humans and the surrounding organisms such as oxygen and food. Understanding species responses to a changing climate may allow us to predict the potential distribution of important food resources, the efficiency of our future marine protected areas, and the species composition of our future oceans.

What implications does this study have

for fishing and future marine nature reserves?

Our ocean’s biota is undergoing a constant change with the shift of our climate. We assume that letting our current MPAs conserve the same habitats and grounds through time may not serve the same amount of protection for the future marine communities, as their distributions are also about to change.

Similarly, and based on our models, fishery grounds are predicted to deepen for cold-water and deep-water species in particular. Conversely, shallow-water species may not be able to deepen to cope with increasingly warming waters. Therefore, they may have to adapt as deeper environments may not serve as an optimal habitat.

How has the planet’s warming had a direct

impact on the Mediterranean Sea in particular?

The semi-enclosed nature of the Mediterranean Sea makes it particularly sensitive to climate change. As a result, it is notorious for having one of the greatest warming rates in the world. For instance, the upper waters of the Levantine basin have a warming rate of about 1.2 ℃ per decade which is about twice the warming rate in the entire Mediterranean Sea, a hotspot for climate change.

Generally, cold Atlantic waters are entering the Strait of Gibraltar. These waters flow across the North African shelf and are becoming constantly warmer, saltier (due to evaporation), and poor in nutrients (due to consumption by organisms) while reaching the Levant, the eastern warm edge of the Mediterranean. These waters continue to flow north and then west until they exit the Mediterranean Sea back to the Atlantic Ocean. This process may take approximately 100 years in terms of residence time.

How has sea temperature changed in the last

100 years?

Globally, according to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it appears that since the 1970s, our oceans are constantly warming and at rates that have near doubled since the early 1990s. As mentioned above, some environments are getting warmer than the global average, and we should remember that each ecosystem has its unique conditions.

How is the migratory pattern different in

warm-water species and cold-water species?

We found that cold-water species are more sensitive to warming. This was evident with greater minimum depth deepenings for cold-water species (i.e species with affinity to cold waters such as the Atlantic mackerel) while compared to warm-water species (e.g., Whiskered sole). This pattern was true for the whole species pool, including fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods.

Before this study, we mainly knew anecdotal examples for species that inhabit shallow water in the Western Mediterranean Sea and dwell in deep waters in the Eastern Mediterranean. Therefore, creating a broad generalization across 236 marine Mediterranean species was an alarming and important understanding.

Were there any key challenges in your research

and how were these overcome?

While conducting a meta-analysis, there are usually many challenges associated with data quality control and standardization across the studies. We had to execute several sensitivity analyses to make sure that our results are not biased by sample locations, sampling intensity, and other potential biases associated with bottom-trawling. After combining all these analyses and closely observing the patterns, we were able to confidently report our results and conclusions.

How should decision-makers prepare in advance

for the deepening of species?

I believe that decision-makers must have detailed plans for the future. For instance, marine protected area planners should also consider including deep habitats and not protecting only shallow and coastal ecosystems. Specifically, I recommend that each MPA should have a species list combined with species traits to understand the proportion of species of various thermal preferences, depth preferences, and levels of generalism-specialism. These may allow better decision-making according to species’ predicted depth changes.

Unfortunately, I believe that some species such as shallow-water species might be at greater risk than others (e.g. herbivores might not find suitable food at depths). This means that protecting them from overfishing might not always be enough.

Do you have any further research you would

like to discuss?

In this study, we mainly underscore species’ predicted depth distributions with warming. We did not have data on whether these species are thriving or challenged by redistributions. It is difficult to understand whether deepening species are increasing or decreasing their fitness. Our current study’s overarching goal is to fill this knowledge gap.

About Shahar Chaikin

I am currently a Ph.D. candidate in Professor Jonathan (Yoni) Belmaker’s lab, School of Zoology, The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel-Aviv University.

I am currently a Ph.D. candidate in Professor Jonathan (Yoni) Belmaker’s lab, School of Zoology, The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel-Aviv University.

My current dissertation looks at how marine species are impacted by climate change and specifically explaining whether some are facing greater risks with warming. To deal with these questions I use both macroecological and local approaches using data science and field samplings.

I am also a co-founder of “Sharks in Israel”, an NGO that helps protect sharks and rays along the Israeli coast.

I am currently a

I am currently a