Kepler and the Witch

This is an essay I wrote for my “Magick, Religion, and Science” class at ASU. I discuss how Johannes Kepler used the power of reason to both discover the laws of planetary motion as well as to save his mother from being convicted of witchcraft.

According to Carl Sagan, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) was the last scientific astrologer.[1] Although people still believe in and practice astrology today, Kepler effectively separated the belief system of astrology from the science of astronomy. Before Kepler, scientific astrologers thought the stars reflected what happened on Earth, but astrology actually had little connection to reality. After Kepler, astronomy presented real physical forces that governed the motions of the planets.[2] A devoutly religious man, Kepler had every reason to put his beliefs before his observations. He even “described his pursuit of science as a wish to know the mind of God.”[3] He was a successful scientist, however, because he accepted the facts over his preferences.[4] Instead of assuming first principles, which was the common practice, Kepler (along with Copernicus and Galileo), pioneered the scientific method by devising theories in accordance with observations of nature itself and translating those theories into mathematics.[5] Kepler believed in a rational and predictable natural world, but he lived in a time of social unrest. In Kepler’s day, the boundaries of magic, religion, and science were undefined and prone to significant overlap. Kepler stands out because he refused to let his preconceived beliefs dictate his findings. In fact, he used his keen intellect, informed by careful observations and reason, to conquer two fallacious arguments that loomed over him. The first led to the discovery of his three laws of planetary motion and the subsequent rejection of the orbital perfection he wanted to believe. The second defeated the formal accusations of witchcraft that had led to his mother’s imprisonment and ultimately saved her life.

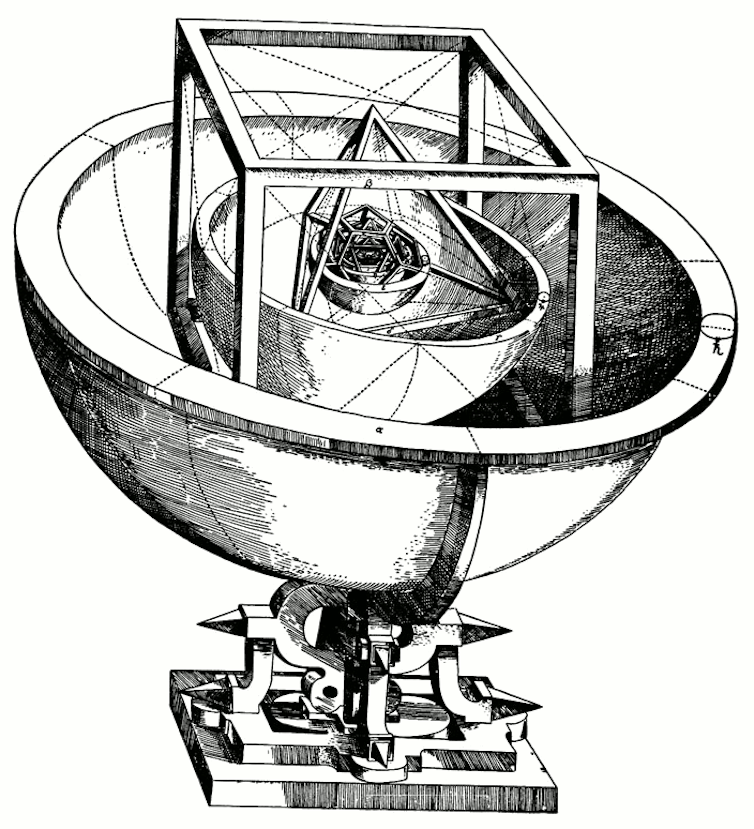

Kepler was born in 1571 and raised as a Lutheran during the Protestant Reformation. At a young age, he went to a Protestant school to be educated for the clergy but ended up becoming a mathematics teacher in Graz. Kepler was trained in Greek, Latin, music, and mathematics. During his studies at the University of Tübingen, he learned about and adopted Copernicus’ heliocentricity.[6] Kepler was curious about the divine plan for the world and was obsessed with understanding the mind of God. He thought of geometry as somewhat synonymous with God’s way of thinking, and he tried to use Pythagoras’ perfect solids to describe the orbits of the known planets. For Kepler, astronomers were “priests of God” who revealed divine order through nature.[7]

In Kepler’s day, astronomy and astrology were interlinked. Astrology had been used all over the world for various purposes, such as divination, calendrical construction, and fortune telling. Greek scientists collected and refined knowledge of astrology, mathematics, and science from other parts of the world to develop practical tools and to set up a mechanistic universe. In the second century CE, Claudius Ptolemaios (Ptolemy) wrote a compendium of Hellenistic astrology and astronomy. He described the cosmos as Earth-centered with perfectly circular planetary orbits. Though his system failed to address retrograde motion, which is impossible in a geocentric model with a motionless Earth, it became the scientific paradigm for the next 1300 years. Later Muslim philosophers, such as Avicenna, argued against the efficacy of astrology and attempted to correct Ptolemy’s errors in order to develop a purer astronomy. In 1543, Copernicus revived heliocentricity from the works of the Hellenistic astronomers, consulted Muslim criticisms of Ptolemy’s model, and mathematically proved that the Earth and planets orbit the Sun.

For Kepler, “only quantitative mathematical proof is a characteristic of objective science.”[8] He agreed with Copernican heliocentricity and rejected most of traditional astrology.[9] Kepler decided that celestial bodies have no influence aside from their light and that astrological effects are due only to the reactions of people’s souls to God’s harmonies or proportions in nature.[10] Though he saw many nonsensical aspects to astrology, Kepler thought there may still be some philosophically interesting astrological realities due to these harmonies.[11] He completely rejected the “low” astrology of folklore, but still practiced the “high” astrology of large-scale matters like weather, which he believed to be part of physics.[12] According to Kepler, much of the content of astrological calendars was mere superstition, but he did not reject astrology as a whole—he wanted to reform it.[13]

When Kepler failed to explain planetary orbits in terms of perfect solids, he thought the problem must have been due to inaccurate observations.[14] To correct the errors, he began working with Tycho Brahe, who had access to the most accurate observations to date. Brahe was known to publicly attack Copernicus’ heliocentricity but privately tried to merge it with Ptolemy’s models. Brahe had the data but needed Kepler’s mind to understand it.[15] After Brahe died, Kepler used his tables to confirm Copernicus’ model, but he was unable to match the data to circular orbits. Kepler was thus forced to reject the idea of circular orbits in favor of elliptical orbits, which showed retrograde motion to be an illusion and matched Brahe’s tables “perfectly.”[16] Though the Church officially endorsed Ptolemy’s model for well over 1000 years and Kepler was upset by the results, he fully accepted the data and discovered the first two laws of planetary motion:

1st Law: A planet moves in an ellipse with the sun at one focus.

2nd Law: A planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time.[17]

After discovering the first two laws, Kepler spent 10 years trying to understand how they related to God’s harmony. He “loathed the ‘imperfect’ ellipses.”[18] Finally, in 1619, he discovered the third law and believed it to reveal the divine mind in creation. He said “I let myself go in divine rage” over the achievement.[19]

3rd Law: The squares of the periods of the planets, the time for them to make one orbit, are proportional to the cubes, the 3rd power, of their average distances from the sun.[20]

For Kepler, cosmological harmony was a consequence of God making the universe as beautiful as possible.[21] The harmony he found turned out to be something he had not expected, but it was the data that let him to his conclusions—not his predetermined beliefs.

Kepler’s discoveries would spell trouble in the Christian world. His elliptical orbits challenged conventional theology and, some believed, could possibly lead to disbelief in, or even disproof of, God. Aristotle had pronounced perfect circles as a sign of perfection. Ptolemy had used perfect circular orbits as a fundamental part of the world. Furthermore, Copernicus’ heliocentric model removed the Earth as the center of the universe. Kepler’s ideas challenged both the perfect nature of God’s creation as well as the authority of the Church. He had mathematically proven that Church doctrine was wrong, bringing to question what other errors the Church had made. Kepler was eventually excommunicated from the Lutheran Church for his beliefs,[22] but his entire life was punctuated by religious conflict and strife. He had grown up during the Protestant Reformation, which pitted Catholics and Protestants against each other throughout Europe. While a math teacher in Graz, he was exiled by Catholics who took over the city in 1598. He fled to Prague to work with Tycho and the Thirty Years War began while he was there; his wife and son died from disease spread during the war.[23] Kepler even experienced the “tidal wave of witch-hunting” in Germany, which consumed thousands of victims, mainly old women.[24] Toward the end of his life, Kepler put aside astronomy to defend his mother against accusations of witchcraft. He would be successful by using the same method of observation, reason, and meticulous explanation that he had used to understand the cosmos.

From the 1590s-1650s, a witchcraft craze swept Germany. Scholars disagree about why it took place, and explanations range from a cleansing of pagan traditions or budding capitalism to a “sex war” or syphilis outbreak.[25] Hartmut Lehmann suggests that the persecution took place to “restore order” to society during the Reformation.[26] Regardless of the cause, people seemed to truly believe that witches existed and that witches were dangerous. Those accused were generally considered guilty qua accused. In 1615, Katharina Kepler’s vindictive neighbor, Ursula Reinbold, accused her of witchcraft. Reinbold claimed that Katharina had bewitched a drink, causing her chronic leg pain.[27] Katharina’s husband, Heinrich, had run away in 1589, leaving her to fend for herself.[28] According to Carl Sagan, Katharina was a “cantankerous old woman” who annoyed local nobility and “sold drugs.”[29] The jury was against her from the beginning and took her emotional resilience as an argument for guilt.[30] Her family members successfully minimized her hardship and prevented torture, but Katharina spent 14 months incarcerated.[31] She finally gained her freedom due to Johannes’ meticulous defense. Kepler identified three main, interlinked causes for his mother’s predicament: enmity, fear against old women, and a new government eager to act. He set out to “discredit every witness through legal reasoning.”[32] He attacked the reliability of witnesses who were too young or had based their claims on hearsay, revealed inconsistencies in witness’ testimony, showed that Ursula had taken the wrong medication, distinguished between natural and unnatural illnesses, and systematically dismantled every claim against his mother. Furthermore, Katharina had taken her own medicine without ill effect and had raised her children to be good Lutherans.[33] According to Ulinka Rublack,[34]

Every element of seemingly damning testimony was therefore addressed and explained in its wider context—of natural disease, a person’s bias, family quarreling, or simple mishaps.

Kepler even argued that old women used folk medicine based on experience which formed a basis for reputable knowledge. In other words, he showed his mother to be a normal person and a pious citizen rather than a superstitious old woman.[35] When confronted with Kepler’s rebuttal, the Tübingen lawyers could no longer justify the charges. As a final attempt to frighten a confession out of her, they gave Katharina a tour of the torture chamber before her release.[36] Unfortunately, she died only 6 months later.[37]

Racked with guilt after his mother’s death, Kepler thought back to the unpublished fantasy he had written in which an Icelandic astronomer, Duracotus, traveled to the moon using magic from his mother, Fiolxhilde.[38] Kepler had given a copy to the teenage baron of Volkersdorf in 1611 and imagined it being circulated to Ursula Reinbold via her brother.[39] He became obsessed with Somnium and decided to publish it as punishment for those who had taken it as a factual account of him and his mother. He footnoted every source from literary works to clearly demonstrate that it had nothing to do with reality.[40] It is uncertain whether the unpublished fantasy did contribute to Katharina’s arrest. Her accusations were clearly a matter of her interactions with the local community, not Kepler’s ideas,[41] but it is possible that his work of fiction played a role. Such a literal interpretation of Somnium exemplifies the melding of magic and science in Kepler’s day.

According to Arthur Beer, “Kepler stands squarely between the prescientific age, with its magical-symbolical description of Nature, and the new science.”[42] Robert Hazen points out that “in spite of the mathematical logic and order that Kepler brought to the heavens, he still had to contend with a superstitious world.”[43] Kepler was a religious man who believed in God and was driven to understand how the world works. He was raised and educated in the Church. He saw persecution, war, and even his own mother’s arrest grounded in religious beliefs. He used science to separate the realities of nature from the fallacious conclusions and superstitions of everyday life. Where others sought evidence to support preconceived beliefs, Kepler formed his conclusions based on observation and mathematics. He thought science had “sprung from superstition in the first place,” and astronomy had grown from a need to foretell the future,[44] but he rejected astrology as based on the choices of humans rather than signs that reflect the nature of the cosmos.[45] He was able to make such distinctions while retaining his core religious beliefs.

When Kepler’s discoveries overturned the accepted, authoritative view of his religious tradition, he sided with the data over what he wished to be the case. He demonstrated that the planets are not deities or personal, he showed that they are not perfect and do not decide the fates of men, and he also explained how their orbits actually work. Although his three laws of planetary motion described the planets as bound to physical, mechanistic forces that did not comply with the geometric perfection expected from a perfect god, Kepler accepted the observations. He was able to adjust his religious beliefs to the revelations of nature. His science was correct and inspired future discoveries. In similar fashion, his skills at observation and reasoning directly resulted in his mother’s freedom. Although Kepler never addressed his belief or disbelief in the existence of witches,[46] he knew his mother’s arrest was based on false accusations. The arguments against her simply did not support the charge. His rebuttal not only proved his point, but also changed people’s minds.

Kepler suffered many hardships and setbacks due to the constant political and religious flux in Germany during his life. As Lutherans and Catholics fought for power and territory, Kepler found himself caught in the middle. When fear of harmful magic from witchcraft swept through the area, his family suffered. Throughout the ordeals, Kepler continued his work separating science from pseudoscience. According to Rublack, human nature is rooted in needs that are difficult to classify neatly as “religious” or “magical.”[47] Kepler believed God put people on Earth so our perceptions would constantly change, and he thought that natural knowledge could not be wholly removed from emotion. That said, reliability was key.[48] He developed a reliable method to explain and predict the celestial motions of planetary bodies that was devoid of magic or hidden influence. As he sought to understand the mind of God, he successfully described the natural world by stripping away ideas that did not fit concrete observations. Kepler paved the way for the dedicated discipline of astronomy without the baloney of astrology attached. He clearly showed, that both astrology and witchcraft, at least in the case of Katharina, were matters of personal fears, desires, and superstitions—not manifestations from supernatural forces able to determine what occurs in people’s lives or to influence the actions of nature.

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” Directed by Adrian Malone. Written by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan, and Steven Soter (Cosmos Studios, Inc., 2000 [Originally aired September 28, 1980]). ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Carl Sagan, The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. London (HEADLINE BOOK PUBLISHING, 1997), 294. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Robert Bucholz, Foundations of Western Civilization II: A History of the Modern Western World. Course Guidebook (The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2006), 56-57. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Patrick J. Boner, “Beached Whales and Priests of God: Kepler and the Cometary Spirit of 1607.” Early Science and Medicine 17, no. 6 (2012), 590. ↑

Arthur Beer, “Kepler’s Astrology and Mysticism.” Vistas in Astronomy 18 (1975), 416. ↑

J.V. Field, “A Lutheran Astrologer: Johannes Kepler.” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 31, no. 3 (1984), 225. ↑

Beer, “Kepler’s Astrology and Mysticism,” 412. ↑

Beer, “Kepler’s Astrology and Mysticism,” 417. ↑

Field, “A Lutheran Astrologer,” 190. ↑

Field, “A Lutheran Astrologer,” 196. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” Robinson points out that Kepler’s laws only hold up in the “ideal world of mathematics … In the world of actual physical things, there are discrepancies.” Daniel N. Robinson, The Great Ideas of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Course Guidebook (The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2004), 130. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Alan Charles Kors, “Galileo and the New Astronomy.” Great Minds of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 3rd Edition. Course Guidebook (The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2000), 131. ↑

Kors, “Galileo and the New Astronomy,” 131. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Field, “A Lutheran Astrologer,” 225. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Hartmut Lehmann, “The Persecution of Witches as Restoration of Order: The Case of Germany, 1590s-1650s.” Central European History 21, no. 2 (1988), 107. ↑

Stanislav Andreski, “The Syphilitic Shock.” David Hicks (ed.). Ritual and Belief: Readings in the Anthropology of Religion, 3rd Edition (Lanham: Altamira Press, 2010), 367. ↑

Lehmann, “The Persecution of Witches,” 108. ↑

Adam Richter, “Kepler in a Witch’s World.” Review of Ulinka Rublack The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Metascience 26 (2017), 191. ↑

Ulinka Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for His Mother (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 39. ↑

Cosmos, “Harmony of Worlds.” ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 203. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 268. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 245. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 247-253. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 251. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 254. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 263. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 269. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 274. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 276-277. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 277-280. ↑

Richter, “Kepler in a Witch’s World,” 192. ↑

Beer, “Kepler’s Astrology and Mysticism,” 408. ↑

Robert M. Hazen, The Joy of Science. Course Guidebook (The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2001), 16. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 288. ↑

Field, “A Lutheran Astrologer,” 201. ↑

Edward Rosen, “Kepler and Witchcraft Trials.” The Historian 28, no. 3 (1966), 449. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 288. ↑

Rublack, The Astronomer and the Witch, 287-288. ↑K

Bibliography

Andreski, Stanislav. “The Syphilitic Shock.” David Hicks (ed.). Ritual and Belief: Readings in the Anthropology of Religion, 3rd Edition. Lanham: Altamira Press, 2010. Pp. 363-396.

Beer, Arthur. “Kepler’s Astrology and Mysticism.” Vistas in Astronomy 18 (1975). Pp. 399-426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0083-6656(75)90120-8.

Boner, Patrick J. “Beached Whales and Priests of God: Kepler and the Cometary Spirit of 1607.” Early Science and Medicine 17, no. 6 (2012). Pp. 589-603.

Bucholz, Robert. Foundations of Western Civilization II: A History of the Modern Western World. Audiobook and Course Guidebook. The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2006.

Cosmos. “Harmony of Worlds.” Directed by Adrian Malone. Written by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan, and Steven Soter. Cosmos Studios, Inc., 2000 (Originally aired September 28, 1980).

Field, J.V. “A Lutheran Astrologer: Johannes Kepler.” Archive for History of Exact Sciences 31, no. 3 (1984). Pp. 189-272.

Hazen, Robert M. The Joy of Science. Audiobook and Course Guidebook. The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2001.

Kors, Alan Charles. “Galileo and the New Astronomy.” Great Minds of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 3rd Edition. Audiobook and Course Guidebook. The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2000. Lecture 29 (Pp. 130-133).

Lehmann, Hartmut. “The Persecution of Witches as Restoration of Order: The Case of Germany, 1590s-1650s.” Central European History 21, no. 2 (1988). Pp. 107-121.

Richter, Adam. “Kepler in a Witch’s World.” Review of Ulinka Rublack The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Metascience 26 (2017). Pp. 191-193.

Robinson, Daniel N. The Great Ideas of Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Audiobook and Course Guidebook. The Great Courses: The Teaching Company, 2004.

Rosen, Edward. “Kepler and Witchcraft Trials.” The Historian 28, no. 3 (1966). Pp. 447-450.

Rublack, Ulinka. The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for His Mother. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. London: HEADLINE BOOK PUBLISHING, 1997.