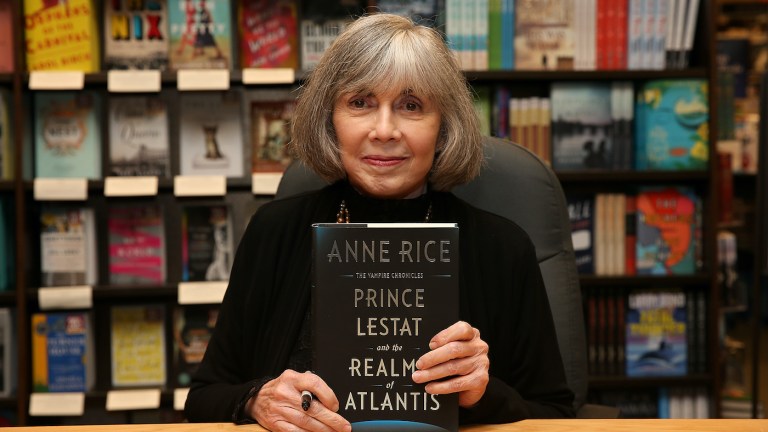

Interview with the Vampire author Anne Rice’s passing leaves a hole in literature which may not be filled for generations.

By Tony Sokol|December 13, 2021|

Anne Rice and Bram Stoker, what other writers have done more to define vampire mythology and culture? Yes, there were stories before and more to come, but Interview with the Vampire, like Dracula before it, set the template for the classic and modern immortal nocturnal narrative.

Stoker’s Dracula was as much a feral creature as the historical figure from whom Stoker borrowed the name. Rice’s characters came from her imagination and had as much of the human essence in their psyches as the flesh between their fangs. They contemplated existential horrors, averted their eyes when loved ones died, and debated the ethics of nutritional hemoglobin, straight from the tap. They did it unblinkingly, and not only because of post-mortem ocular putrefaction.

Interview with the Vampire was originally a 38-page short story Rice wrote in late 1968 through early 1969. She extended it out of grief in 1972. Her five-year-old daughter, Michelle, died of acute granulocytic leukemia, a cancer which affects blood and bone marrow. Rice’s incredibly tortured personal reality is where modern vampire art was birthed. It is blood-borne. It is lethal. It begs so many questions, and mocks so many of the easy answers people offer to alleviate despair. It birthed an undead mythology and philosophy which reverberates to each generation.

Louisiana, Transylvania – Native Soil or Bayou Mojo

Anne Rice was born Howard Allen Frances O’Brien in 1941. Yes, Howard. She was named after her father by a Bohemian mother. When asked her name on the first day of kindergarten, she answered “Anne” and had it legally changed in 1947, according to the authorized biography Prism of the Night by Katherine Ramsland. Anne was 15 years old when she lost her mother to alcoholism, and her father placed her and her three sisters in a boarding school at the Gothic and foreboding St. Joseph’s Academy in Baton Rouge. Not as well known as Dracula’s castle, its shadows touch every nuanced rebellion Rice would quietly incite.

Louisiana is Anne Rice’s Transylvania, but she knew it far more intimately. Stoker researched his titular character’s origin in broad strokes. Rice was born in New Orleans and while she lived in quite a few different locations, including Texas and Hollywood, she always called New Orleans her home. Readers associate her with its Garden District, and her characters originate in wards. Louis de Pointe du Lac, the vampire who is interviewed in Interview with the Vampire, was a slave-holding plantation owner in antebellum New Orleans. He travels the world after escaping his vampire maker, Lestat de Lioncourt, journeying from the theaters of Paris to the saloons of San Francisco. But New Orleans is his spiritual home.

Because of Rice, Louisiana is now associated with the vampire. Charlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire Mysteries, which was adapted into HBO’s influential series True Blood, took place in Bon Temps, Louisiana. The state has a long and chronicled history of vampire-like activity, both legendary and surprisingly real, and sad tales of wayward innocents.

Remorseful Vampires

Rice’s vampires weren’t the first regretful bloodsuckers. In interviews, Anne herself cited Gloria Holden’s ambiguously carnal Countess Maria Zeleska in the 1936 Universal horror, Dracula’s Daughter, as an inspiration. Dark Shadows’ Barnabas Collins, played by Jonathan Frid, went as far as to bribe a friendly scientist to try and reverse the process which turned him into the undead. Even Count Dracula (John Carradine) went to Dr. Franz Edelmann (Onslow Stevens) for a cure to vampirism in House of Dracula (1945), as did biochemist Dr. Michael Morbius, who attempted it on himself in Marvel Comics’ Morbius. While none of them suffered biter’s regret like Lon Chaney Jr.’s werewolf in The Wolf Man, they fretted when they fed. Some were even prone to play sympathy games with their food.

“To die, to truly be dead, that must be glorious,” the Transylvanian count pondered in Dracula. The depths of his Eastern European philosophies laid cynically shallow. “Do you know what it means to be loved by Death,” Interview with the Vampire asked. “Do you know what it means to have Death know your name?”

Rice’s characters thrived on their immortality because it fed their hunger for meaning and tweaked their eternal curiosity. They could ponder the fates of mankind and beyond, measure death by the gallon, sin by the moment, and still procure dinner for two before the sun rose. Rice’s vampires were animals, beasts even, but they were thinking beasts. She taught even the most over-thinking vampires to explore the possibilities, with an eye towards ever-elusive karmic retribution, and go for the jugular.

“What we have before us are the rich feasts that conscience cannot appreciate and mortal men cannot know without regret,” we read, and Rice concisely sets out, for the first time with such eloquent clarity, the choice that lies beyond the veil. It is more than hunter and prey, and yet as simple an equation. “God kills, and so shall we; indiscriminately He takes the richest and the poorest, and so shall we.”

We’re a Happy Family

Morality and immortality make for strange bedfellows. What is acceptable today got you burned at the stake centuries ago. The attitudes of a few years’ past can cancel your present, and Rice forever straddled attitudes yet to come. It has been said the character Claudia is based on Rice’s daughter Michelle, which explains the lingering pain of losing that character. But Rice twists this agonizing scenario until it redefines the nuclear dysfunctional family itself on a vampire’s terms. Lestat, Louis, and Claudia stay together for 65 years in Interview with the Vampire. Normal parents would have been throwing hints sometime around graduation.

Did Lestat make Claudia to save his relationship with Louis? Is this like having a child to save a marriage? What is fair about a mentally cognizant teenager, and then adult, stuck in a six-year-old’s body? Claudia is not acceptable in the world of the vampires, and inexplicably twisted in the world of the breathing. Is the relationship paternal? Incestuous? Rice took the time to pose new questions, expanding the emotional vocabulary of vampire fiction, but also of the horror genre and the audience at home. This continues as characters within all genre works, page or screen, now routinely dig at the deeper questions. They’re not afraid anymore. Rice did it without really scaring us.

Fluid Sexuality

Rice’s vampires live in a world of decadence and carnality. Age has taught them pleasure lies in diversity and expansion. Publisher Alfred A. Knopf bought the novel in 1974, paying Rice an advance of $12,000. Interview with the Vampire hit bookstore shelves on May 5, 1976.

Critics attacked its dark themes and overt eroticism. Some say Rice romanticized the vampire beyond its sinister limits. Her vampires are sexy, beautiful, self-determining creatures with the power to traverse heaven, hell, and time, as they would go on to do in Memnoch the Devil. Rice freed them from the petty morality of traditional social repression, and the limiting sensual expression of popular genre release.

Vampire lesbianism had always been projected through the male gaze. Ingrid Pitt in The Vampire Lovers (1971)–based on Joseph Sheridan LeFanu’s 1872 seminal vampire work Carmella, or Susan Sarandon and Catherine Deneuve in The Hunger, broke ground for sexual expression. But both films were made because it was a turn on for the director, producer, and/or mass audience.

Rice’s erogenous fluidity is a vampiric reality. What does anything matter if it truly all turns out to be exactly the same? There are no gender assignments in androgynous prose, no term limits on sexually active verbs. Male and female characters are defined through ability, survival, and adaptability. Vampiric mentorship also has no assignments. “Let the flesh instruct the mind,” Rice wrote

Mentors and Reluctant Students

Lestat turns and instructs Louis on his new existence, which is more than the older European vampire got when he was initially turned. This is the core of the most influential dynamic Rice brings to modern vampire fiction. Louis sees his supernatural impulses as unnatural while Lestat has lived long enough to know it’s the most natural thing in the universe. It is the natural order.

For motion pictures and television, the first and most prevalent takeaway from this was the importance of contrasting hair color. In The Lost Boys (1987), sun-bleached hemoglobin-sucker David (Kiefer Sutherland) shares takeout with the new Jim Morrison-wannabe-lookalike in town, Michael (Jason Patric), a very reluctant nibbler. While this could have easily moved into the openly sexual spectrum Rice found so easy to lay out, the two male vampire characters have Star (Jami Gertz), a female character, to assure the audience of their heteronormativity.

It is the same function Buffy Summers plays between Angel (David Boreanaz) and Spike (James Marsters) on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Sookie Stackhouse (Anna Paquin) convinced Bill Compton (Stephen Moyer) and Eric Northman (Alexander Skarsgård) to indulge in their mutual lust for her in True Blood. By the time The Vampire Diaries hit the CW, Stefan (Paul Wesley) and Damon Salvatore (Ian Somerhalder) were vampire brothers, and all homoerotic tension was annulled.

READ MORE

Vampire Movies’ Favorite Big City Hot SpotsBy Tony Sokol

What We Do in the Shadows: Ranking the Best VampiresBy Alec Bojalad

Vampire literature has not stayed so static. There have been blockbuster films made out of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight, and underground masterpieces like the many works of Poppy Z. Brite, the professional name of Billy Martin. All of which owe something to the author who invented Lestat.

Rice caught a genre in flux and a culture in need. Her influence extends to the clubs and underground gatherings of the vampire community, where the decadence of the novels can be experienced in a natural setting: with music and dancing, something Rice liberally sprinkled onto her pages.

Rice’s output, of course, expands beyond the vampires who appeared in Vampire Lestat, The Queen of the Damned, and other books of the Vampire Chronicles series. She also wrote about witches, in The Witching Hour, which began the Lives of the Mayfair Witches trilogy. Her ghost story, Violin, came out in 1997. She wrote historical novels, like The Feast of All Saints, and Cry to Heaven. Under pen names, the former Howard O’Brien published erotic novels, such as The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty, Beauty’s Punishment, Beauty’s Release, Belinda, and Exit to Eden, which was adapted into a film.

“Evil is always possible,” Rice wrote in Interview with The Vampire. “And goodness is eternally difficult.” Her later books struggled with this idea as they eventually took a more difficult path. She chronicled the life of Jesus in the trilogy of books Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt, Christ the Lord: The Road to Cana, and Christ the Lord: Kingdom of Heaven, and wrote the first two books in her Songs of the Seraphim series: Angel Time and Of Love and Evil. It is all too clear Rice moved on from the vampire literature she altered, but her influence will continue to bring reminders. For the Blood is the Life. Rice brought art to bot

Written by

Tony Sokol | @tsokol

Culture Editor Tony Sokol is a writer, playwright and musician. He contributed to Altvariety, Chiseler, Smashpipe, and other magazines. He is the TV Editor at Entertainment…