by Eric Diaz

May 28 2021

Ask someone to name the most influential piece of vampire fiction ever, and they’ll probably say Bram Stoker’s Dracula. And in general, that is true. But the little-known sequel to Universal’s adaption of Dracula, 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter, might have had the biggest influence on modern undead storytelling. Granted, it took some 30 years for this entry—the tale of a bloodthirsty Countess who wishes she were a mortal—to sink its fangs into popular modern myth. So if Dracula is the father of pop culture vampires, then his daughter is their underappreciated mother.

Universal Pictures

The Original Vampire Sequel

When Universal’s Dracula hit the big screen in 1931, its interpretation of the title character permanently embedded the image of the Transylvanian count in the popular consciousness. No matter how many other on-screen Dracs there have been, Bela Lugosi’s performance created the template we all know. Every parody of Dracula, from Count Von Count on Sesame Street to Count Chocula, took their cue from Lugosi. Tod Browning’s film also cemented the notion of the vampire as an unrepentant bloodsucker, swooping into a locale and draining the town dry. Pure predatory evil personified.

Dracula‘s less celebrated sequel actually wound up a greater indicator of what the vampire genre would eventually become. However, it would take several decades to get there. Universal released Dracula’s Daughter five years after the Bela Lugosi original. Originally, the film was meant to be a father/daughter extravaganza. Oddly, it didn’t star Lugosi at all; Universal even paid Lugosi to not be in the movie, and a wax effigy of his face was created to stand in for his corpse. Instead, the entire focus was ultimately on the titular daughter of the Count, played by English/American actress Gloria Holden.

Cinema’s First Tortured Undead Soul

Universal Pictures

Dracula’s Daughter picks up right where Dracula ended, after Dr. Van Helsing had staked the Count through the heart. Dracula’s daughter, Countess Marya Zaleska (Holden), shows up in England with her manservant, Sandor (Irving Pichel); the pair steal her father’s corpse from Scotland Yard and cremate it in a ritual. All this in hopes that the destruction of his physical body would break her curse of vampirism.

Sadly, the ritual doesn’t work, and the Countess retains her bloodlust. Marya continues to hate her vampiric nature, and wishes to be free of causing harm to others. (Something dear old dad had zero problems with.) The Countess starts her nightly hunting again, hypnotizing her victims with her exotic jeweled ring. With her Joan Crawford eyebrows and Bette Davis eyes, she’s ’30s glamour with a Gothic edge, stalking the streets of London for prey.

Universal Pictures

She then gets the idea that a handsome young psychiatrist Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger) can break her need for blood. Again, no such luck. Instead, she becomes romantically obsessed with him, which infuriates the jealous Sandor. In a very racy scene for 1936, the Countess takes in a beautiful street waif named Lili (Nan Grey) to “paint a portrait of her.” Instead, she feeds on her. The scene is so rife with lesbian subtext that it’s barely even subtext.

Although the girl survives the attack, she later dies when recalling the episode under hypnosis. Unable to free herself from her affliction, the Countess embraces it. She flees back to her home country of Transylvania; there, she lures her newfound obsession Dr. Garth to try to turn him into her eternal vampire companion. Sandor kills the Countess when he realizes she has chosen the new guy over him. The film’s “wicked woman” dies, per the demands of the regulatory Hays Code.

Life After Death

Universal Pictures

Dracula’s Daughter wasn’t the hit that Dracula was. Box office records from those days remain elusive; but the movie effectively ended the first Universal Monsters wave, until 1939’s Son of Frankenstein. Dracula’s Daughter only found a second life on the “creature features” of 1950s TV, hosted by the likes of Vampira. (Herself a “daughter of Dracula.”) There, a new generation latched onto the film. And some of those kids would grow up to make significant vampire content of their own, media that would change the landscape of undead fiction.

There are two key ways Dracula’s Daughter was influential. It was, by all accounts, the first on-screen representation of the reluctant vampire archetype. Instead of reveling in her evil ways, Countess Zaleska shunned and felt shame over her own bloodlust. She just wanted to be an ordinary mortal, despite clearly relishing in the hunt. Most vampire fiction in the years to come kept to the Dracula mold, including Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot. But in the long run, the influence of his daughter would prove a stronger bloodline.

The Vampiric Offspring of Dracula’s Daughter

Universal Pictures

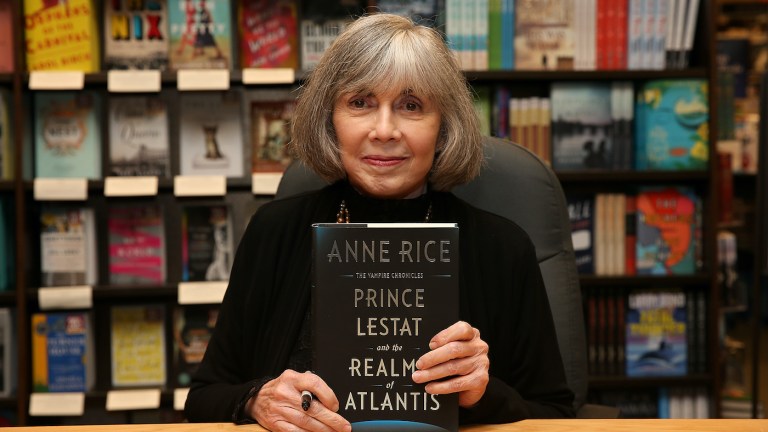

Dracula’s Daughter ultimately led to similar vampiric portrayals in the immensely popular TV soap Dark Shadows, and Marvel Comics’ Morbius the Living Vampire. Both Dark Shadows’ Barnabas Collins and Marvel’s Michael Morbius seek professional help to try to break their addictions, much like the Countess. Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles don’t really go this psychiatric treatment route, but Rice would cite the movie as a childhood favorite. She even named the fictional vampire bar in her books after Dracula’s Daughter. Not to mention, she built her entire narrative across several books upon the notion of the remorseful vampire.

Universal Pictures

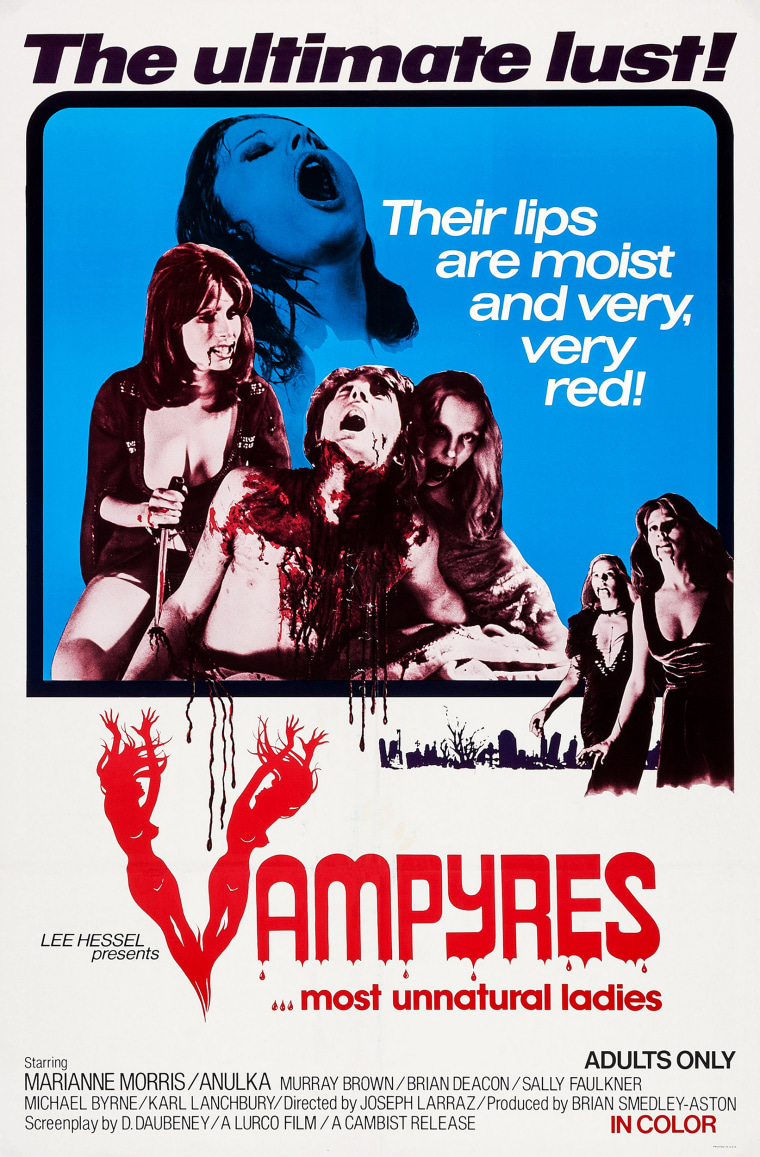

And then, there’s the lesbian angle. Decades before vampiric eroticism between two women in movies like The Vampire Lovers, Vampyros Lesbos, or The Hunger, Dracula’s Daughter played up the angle of same-sex lust. The novel Carmilla had famously already done this in the 19th century. But on screen, Countess Zaleska got there first.

Of course, given that this was the ’30s, this desire was explicitly coded as something perverse. Not exactly a positive portrayal. But in an era where LGBTQ people were essentially invisible onscreen, any representation was noteworthy. Even this relatively toned-down expression of homosexuality made Universal executives very nervous. Regardless, decades of onscreen vampiric lesbian women owe Dracula’s Daughter a debt.

At only 71 minutes long, Dracula’s Daughter is still a breeze to watch. And it has more Gothic atmosphere than similar Universal horror films of the era. Yes, it is campy to modern eyes. And its LGBTQ undertones are also extremely tame by today’s standards. But it is definitely worthy of one’s time. If only to discover the source of so many of the modern vampire storytelling tropes we enjoy so much in the 21st century.